Cells act as early danger alarm for marine wildlife

QUEENSLAND SCIENTISTS ARE building a library of cell lines by collecting skin-cell biopsies from live animals and harvesting organ cells from those that have been washed ashore.

The cells are cultivated and stored in the lab, where a range of chemicals can then be tested on a variety of species simply by adding the toxicant to the cells. The method will allow scientists to test the reaction of cells to toxic contaminants quickly and without the need of a live specimen.

Jason van de Merwe, a research fellow at Griffith University in Queensland and a wildlife ecologist by trade, said current water-testing methods were time consuming, expensive and often ineffective.

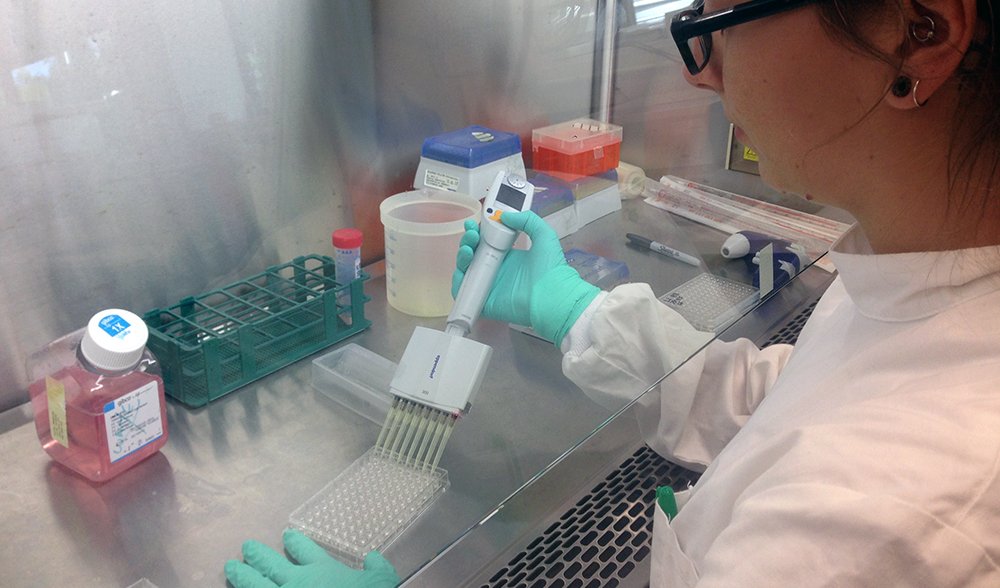

PhD student Kimberly in the lab. (Image courtesy Kimberly Finlayson)

“With the cell lines, if there are changes to water quality, we will be able to quickly test how they might impact the turtles and dolphins in these areas,” he said.

For example, in the event of a dredging or an oil spill near to where turtles and dolphins live, the team is able to get to the scene, take a water sample, then head back to the lab for testing.

“Because we have cells in the lab, we can test that water on the cells to see how they react,” Jason said. “It acts as an early warning sign to changes in water quality – if the cells react, then we would inform authorities.”

Understanding the effects of contaminants

“There’s been a lot of research in the area so it’s amazing how little we know about these contaminants,” PhD student Kimberly Finlayson said. “There’s a new chemical created every three seconds but we know so little about the effects.”

They do know that chemicals are accumulating in large marine animals, like turtles and dolphins, she added. “But right now there are a lot of unknowns when it comes to the impact of these contaminants on the health of these animals.”

Jason said that, by exposing the cells to toxicants, they can determine which chemicals are more – or less – dangerous. “Mercury is the most toxic of the metals we have tested so far,” he said. “We’re a bit concerned.”

“We’re still some way off making a direct link in what we see in the cell level to what we see in the organism level, but to do research in large endangered animals it’s important to study these kinds of contaminants.”

Kimberly has a passion for turtles in particular and wants the project to lead to better conservation and management.

“If we find that these contaminants are having an effect – and we don’t know yet – this information can be passed on to policy makers and decision makers,” she said. “What we can do is unlimited. If you can establish cells for a turtle, then you can do a dolphin and a wide variety of animals to see the large-scale effect these contaminants are having.”

READ MORE:

- Pulling the plug on plastic

- Hybrid turtle possible first in Australia

- Dolphin ‘mothers group’ discovered