Ultimate guide to Australian sharks

Beautifully attuned to a life under water, sharks have patrolled the oceans for more than 400 million years.

While more than 400 species of sharks are found worldwide today, about 170 of them inhabit Australian seas, from the world’s largest, the whale shark, to one of the smallest, the pygmy shark, and of course, the equally fascinating and fearsome great white.

The Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, is particular hotspot of shark diversity in Australia with more than 50 species.

Shark populations around the world have plummeted as the human population has skyrocketed. Largely due to over-fishing, more than 200 shark species are currently listed as threatened, and 50 as vulnerable, by the IUCN. Only three sharks (great white, whale and basking) are protected internationally.

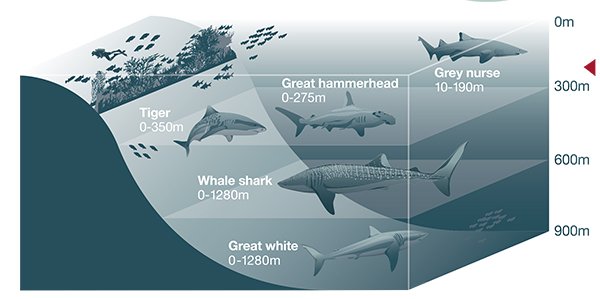

Common shark habitats

Sharks occur in depths up to 3000m in the world’s oceans for a variety of reasons, the most notable of which is food availability. In general, the least threatening species to humans live on the ocean floor and are smaller animals. Larger sharks, including great whites, tiger sharks and whale sharks, travel more widely and have greater depth range in the water column.

Great whites dive deeper than 1km and are seasonal visitors to temperate coastal waters, lured by the likelihood of a feed at seal and sea-lion rookeries and haul-out areas. Find the truth about 10 shark myths here.

The great white is the most threatening species cruising our coastline. The largest recorded great white was caught in 1978 off the Azores, a Portuguese archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, roughly 1500km from Lisbon. It was measured by an observer at 8.8m and was estimated to weigh more than 4.5 tonnes.

Most sharks can’t accelerate quickly because of their tail shape, which is designed to push them towards the ocean floor as they hunt. but a few species have enough power to launch themselves out of the water. Some species, such as thresher sharks, employ their speed and agility in unusual methods of attack.

All shark species constantly shed and replace their teeth. Some lose up to 35,000 in a lifetime.

Little is known about when and where some sharks reproduce, but a great white nursery was recently found near Port Stephens in NSW.

Other sharks are known to be fantastic navigators that can migrate great distances across the world’s oceans. In rare cases, sharks have been known to react to the full Moon.

Some sharks are unable to distinguish between colours, seeing the world in shades of grey and green, say researchers at the University of Western Australia. Monochromatic vision is rare among land species, because colour vision is a tool for survival in terrestrial habitats. But it is less important in the marine environment, where colours are progressively filtered out at depth and survival depends on distinguishing contrasts and shadows to determine whether a shape in the gloom is prey or predator.

Sharks attacks or encounters?

Though it may seem like shark attacks are more common than in the past, the chances of an encounter are still quite rare.

According to the Australian Shark Attack File, kept by researchers at Sydney’s Taronga Conservation Society, there have been 877 shark attacks in Australia since records began in 1791, and 216 of these have been fatal.

All up, about 30 per cent of shark attacks are fatal.

On a worldwide scale there had been 2463 confirmed, unprovoked shark attacks between 1580 and 2011. Australia is the nation with the second highest number of shark attacks (after the US) and the highest number of fatalities (217).

In 2013 an international research team examined global shark encounter data and discovered that the term ‘shark attack’ is widely used to describe almost all interactions between humans and sharks, even those that involve no physical contact and do not lead to injury. They argue that shark attacks should, in many cases, be described instead as encounters.

Nevertheless, in a 10-month period up to July 2012, five people were likely killed by great white sharks off the coast of WA – enough to have the region dubbed the ‘shark attack capital’ of the world. The reasons are unclear, but other experts argue humans are to blame for an increase in attacks. If you do encounter a shark, there are steps you can take to minimise the risk of being attacked.

Sometimes culls of sharks are mooted after attacks, but they have little effect on minimising the threat and provoke outrage from conservationists. In other cases shark repellents, based on reactions to smells tastes and sounds have been developed. One cage tour operator has found that great white sharks are attracted to music by Aussie band AC/DC.

The largest shark ever

Carcharodon megalodon, the largest shark ever to have lived (16 – 1.6 million years ago), is a close relative of the great white. Fossil evidence suggests it grew to a length of 16m, had jaws that were more than 2m wide and sported teeth measuring up to 21cm.

It’s likely that a large megalodon weighed more than 25 tonnes. In comparison, the great white grows to 6m, weighs up to 2.2 tonnes and has 5cm-long teeth.

Australia’s common shark species:

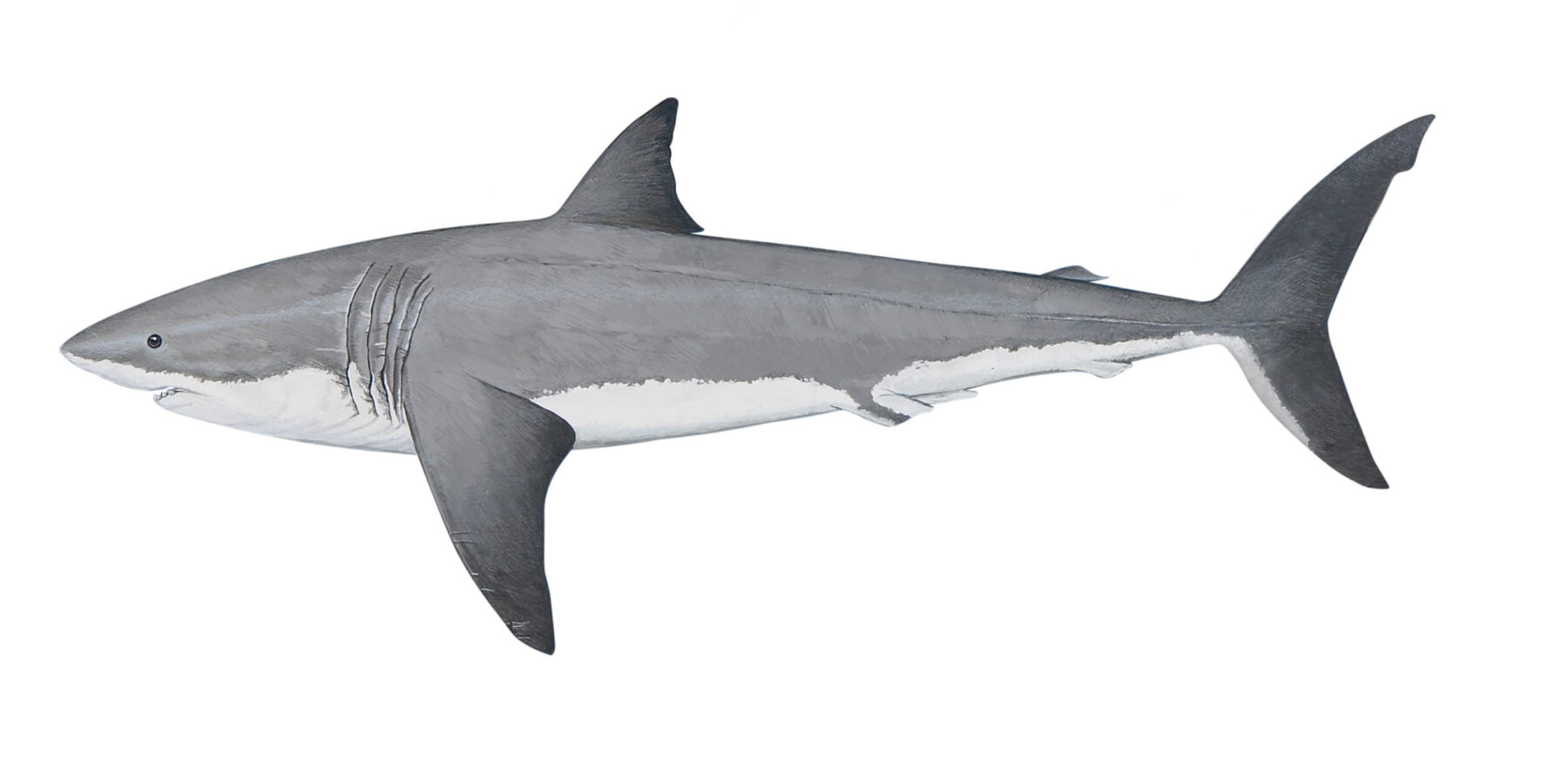

Great white shark

Carcharodon carcharias

IUCN status: vulnerable

Size: up to 6m

Protected throughout Australian waters, the largest flesh-eating shark in the world’s oceans is responsible for the majority of unprovoked attacks on humans. It favours cool, shallow, temperate seas, and is most commonly found in southern Australian waters from Exmouth, WA, to southern Queensland. Feeds on fish and marine mammals such as seals.

Whale shark

Rhincodon typus

IUCN status: vulnerable

Size: up to 14m

The world’s largest living fish, this gentle giant is often found near the surface, where snorkellers can swim alongside it. Highly migratory and found in tropical and subtropical oceans worldwide, it appears alone or in large groups. It filterfeeds on plankton, but also eats prawns, crabs, schooling fish and occasionally tuna and squid.

Port Jackson

Heterodontus portusjacksoni

IUCN status: least concern

Size: up to 1.65m

With a pig-like snout, conspicuous ridges above the eyes and a harness-like pattern across the shoulder, this is a distinctive-looking shark. Frequently seen by divers in rocky gullies and caves throughout its range – south from the Queensland-NSW border to the Houtman Abrolhos, WA, including Tasmania – it feeds at night on starfish, sea urchins, sea cucumbers and molluscs. It poses no threat to humans unless provoked.

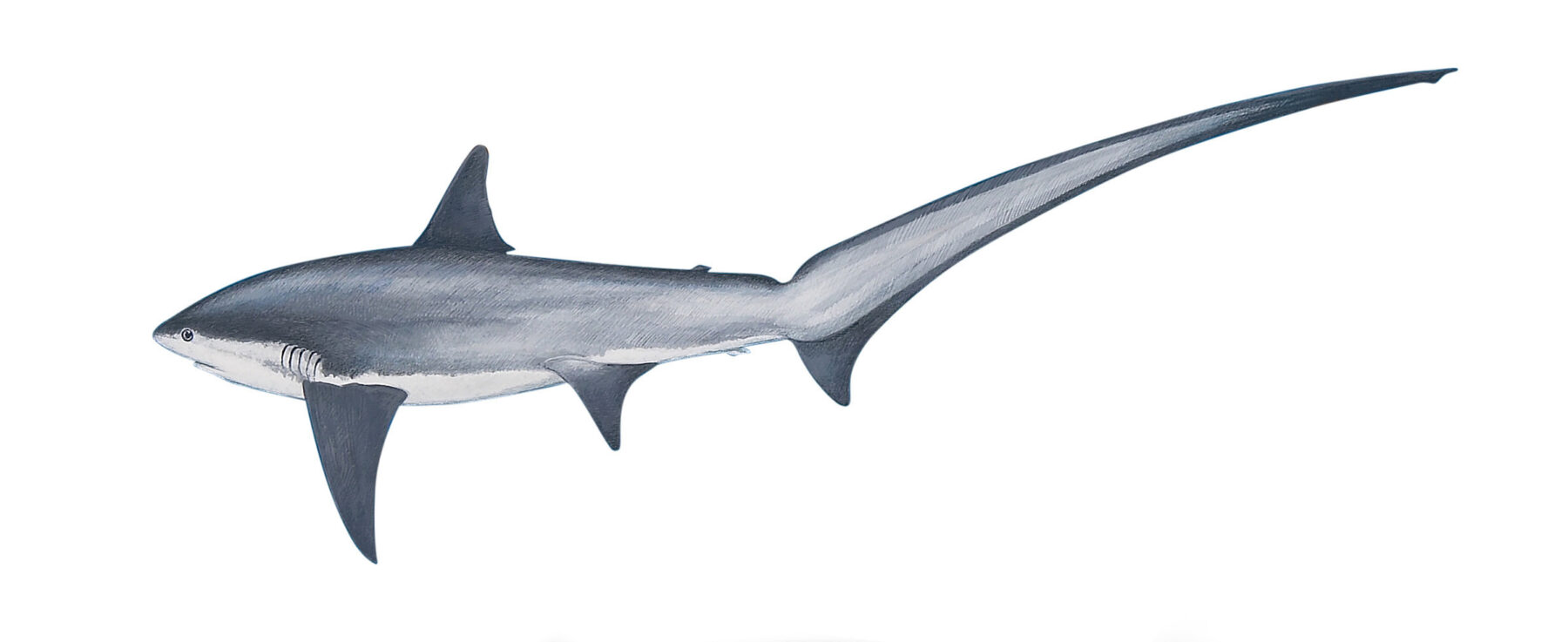

Thresher

Alopias vulpinus

IUCN status: vulnerable

Size: up to 5.5m

Immediately recognisable by its long tail – which it uses to herd and stun squid and schools of fish – this shark can leap up to 6m out of the water. It’s widespread and common in tropical and temperate waters worldwide; its Australian range stretches from Broome, WA, to Brisbane, Queensland, including Tasmania. While not aggressive towards humans, this is a large, powerful shark.

Zebra shark

Stegostoma fasciatum

IUCN status: vulnerable

Size: up to 2.4m

This harmless reef-dweller is charming in appearance and nature. Named for the stripes on juveniles, which morph to spots in adulthood, it’s often seen by divers resting on the sea floor and propped up on its pectoral fins, facing into the current. It eats gastropods, crustaceans and fish, and is found in Australian waters north from Sydney around to Port Gregory, WA.

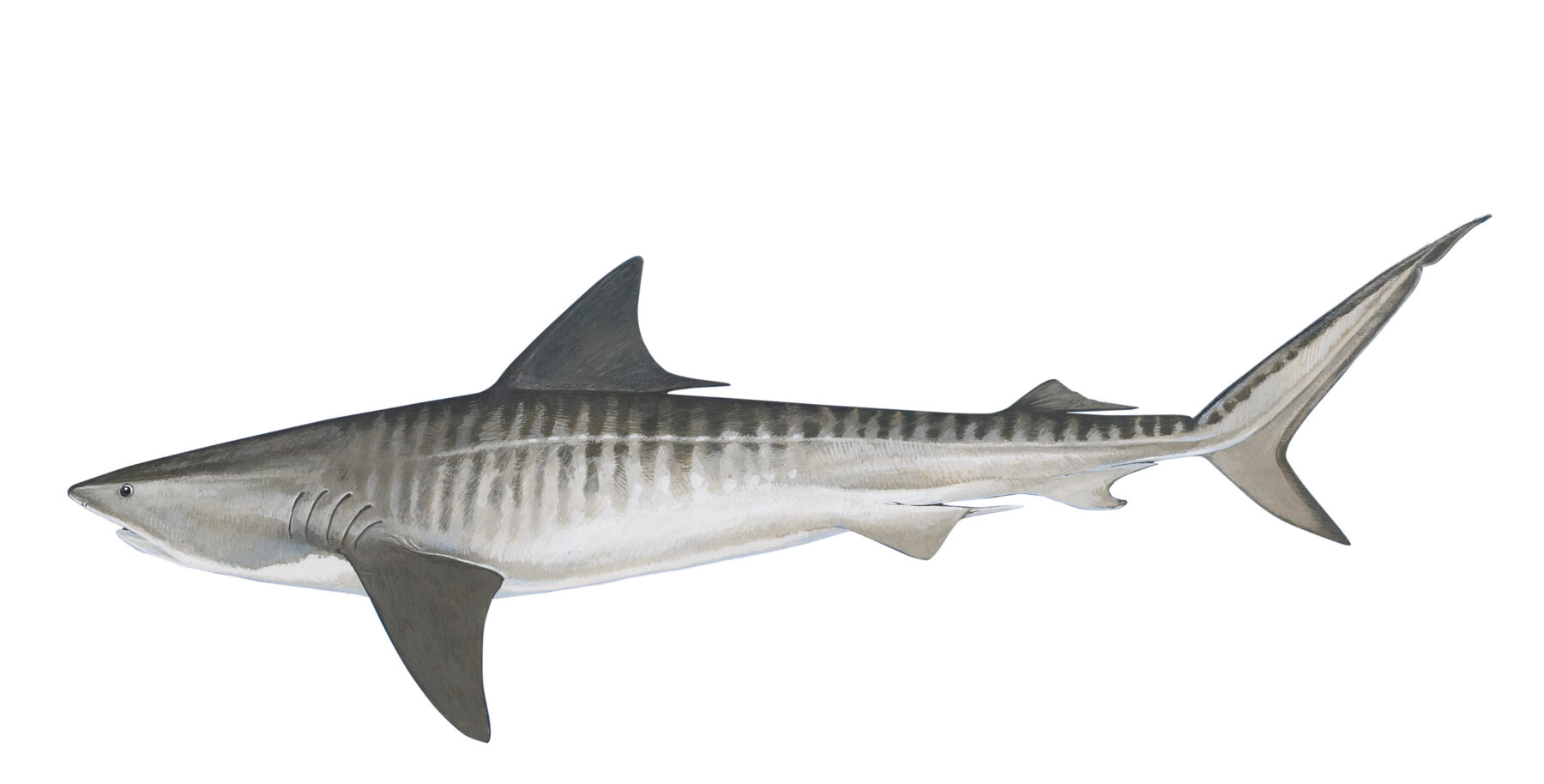

Tiger shark

Galeocerdo cuvier

IUCN status: near threatened

Size: up to 6m

The tiger shark is the tropical equivalent of the great white and highly dangerous. A true scavenger, it eats turtles, seals, whales, jellyfish and stingrays, plus livestock and people unlucky enough to fall overboard. It’s found in northern waters from NSW to Perth, WA, and from reefs to open ocean.

Tasselled wobbegong

Eucrossorhinus dasypogon

IUCN status: near threatened

Size: up to 4m, but often much smaller

Wearing a patterned suit that blends in with the reef floor, this bottom-dweller inhabits tropical waters from Port Hedland, WA, to Bundaberg, Queensland, as well as Indonesia and New Guinea. It feeds on fish and invertebrates, and can be dangerous when provoked or disturbed.

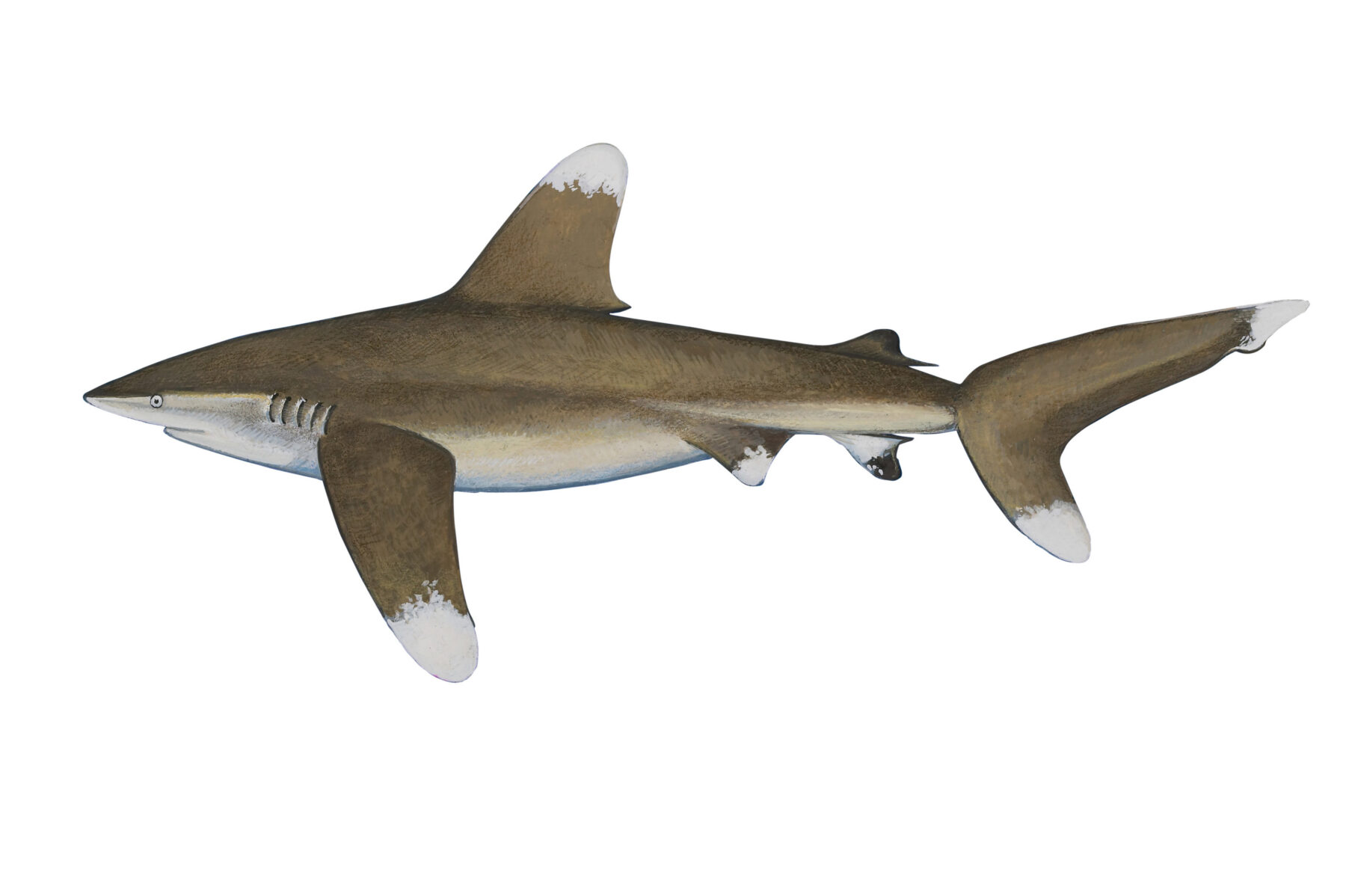

Oceanic whitetip

Carcharhinus longimanus

IUCN status: vulnerable

Size: up to 3m

This shark prefers warm, deep waters and is found around Australia’s north from NSW to Perth, WA. It eats everything from fishes and squid to whales, sea birds and turtles. Many open-ocean attacks on humans after air or sea disasters are attributed to it.

Blacktip reef

Carcharhinus melanopterus

IUCN status: near threatened

Size: up to 1.4m

Known to nibble on people’s feet and legs in the shallows, this species is not generally considered dangerous. Although fairly common and wideranging in the tropics, it is fished and has a long gestation time, making it potentially vulnerable. It’s found in northern Australian waters from Shark Bay, WA, to Brisbane, Queensland, and eats reef fish, crustaceans and squid.

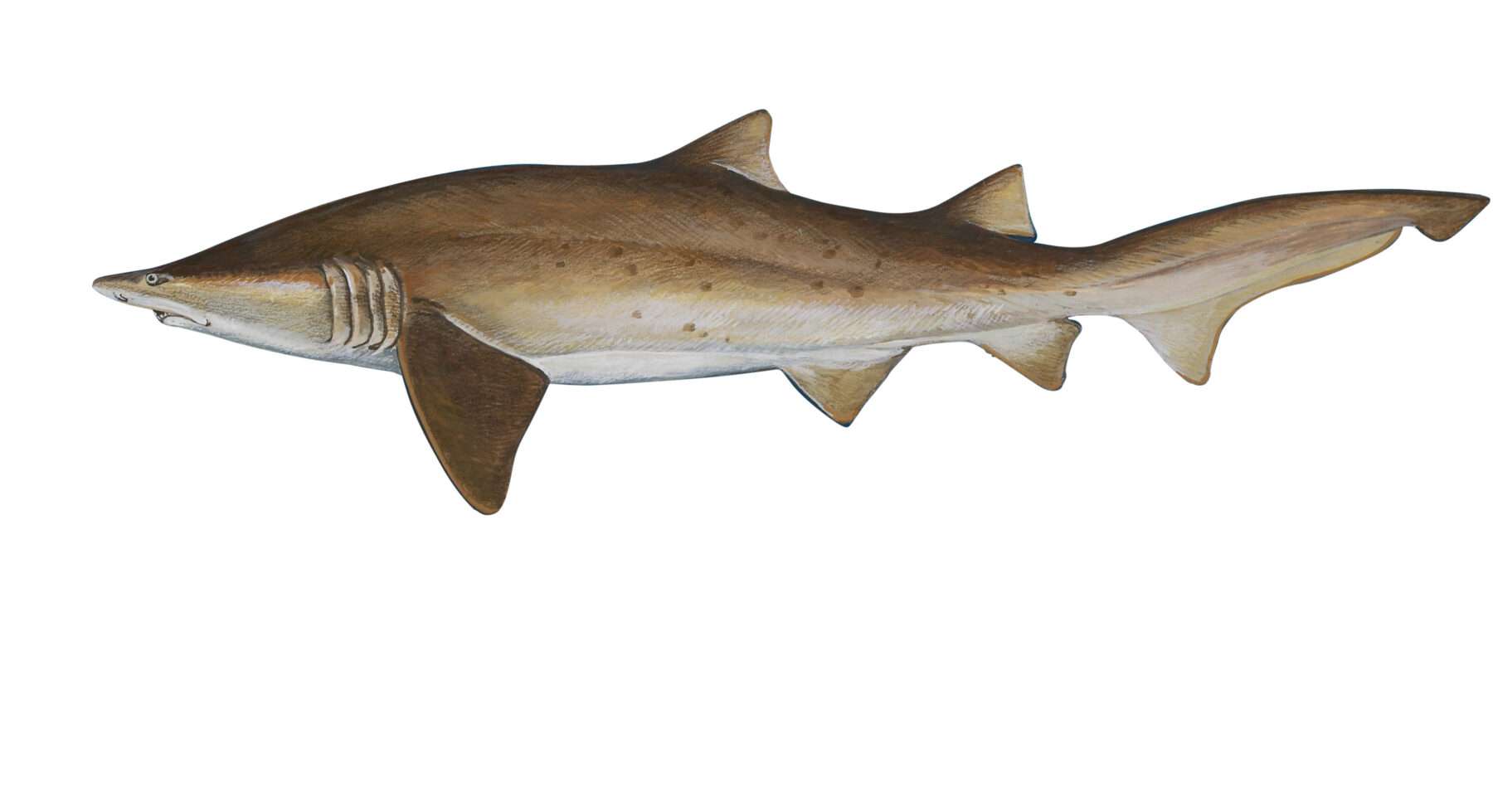

Grey nurse

Carcharias taurus

IUCN status: vulnerable

Size: up to 3.2m

Protected in NSW and Queensland, the grey nurse looks fearsome thanks to its exposed, razor-sharp teeth, but is not considered dangerous. It’s found in all Australian waters except Tasmania. It eats fish, rays, squid and crustaceans, and is often seen near the sea floor.

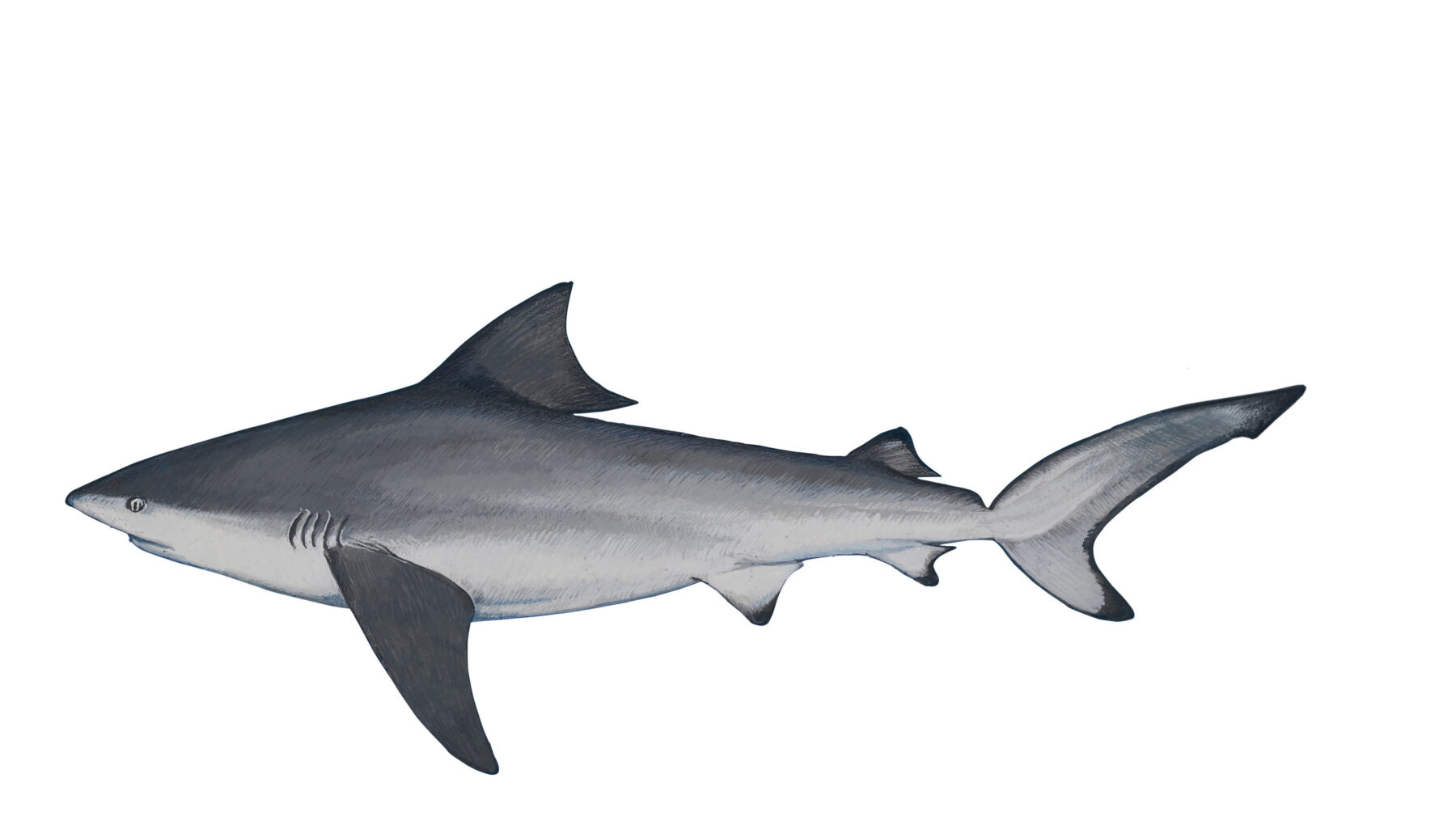

Bull shark

Carcharhinus leucas

IUCN status: near threatened

Size: up to 3.5m

This aggressive species has powerful jaws and eats almost anything: other sharks, dolphins, rays, fish, turtles, birds and molluscs. It can penetrate freshwater river systems and has been known to take cattle, dogs and people. It’s widespread in tropical and warm-temperate seas.

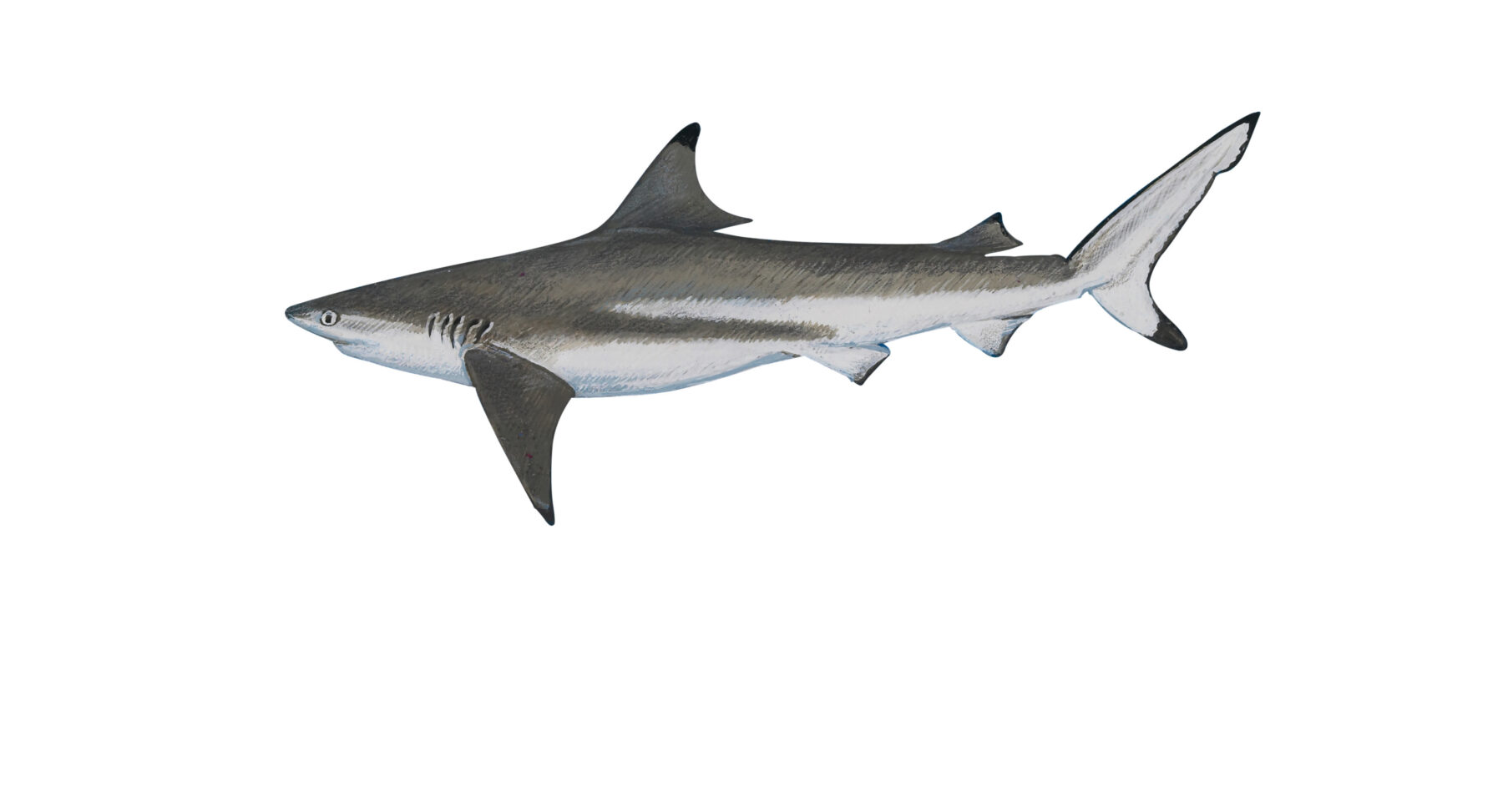

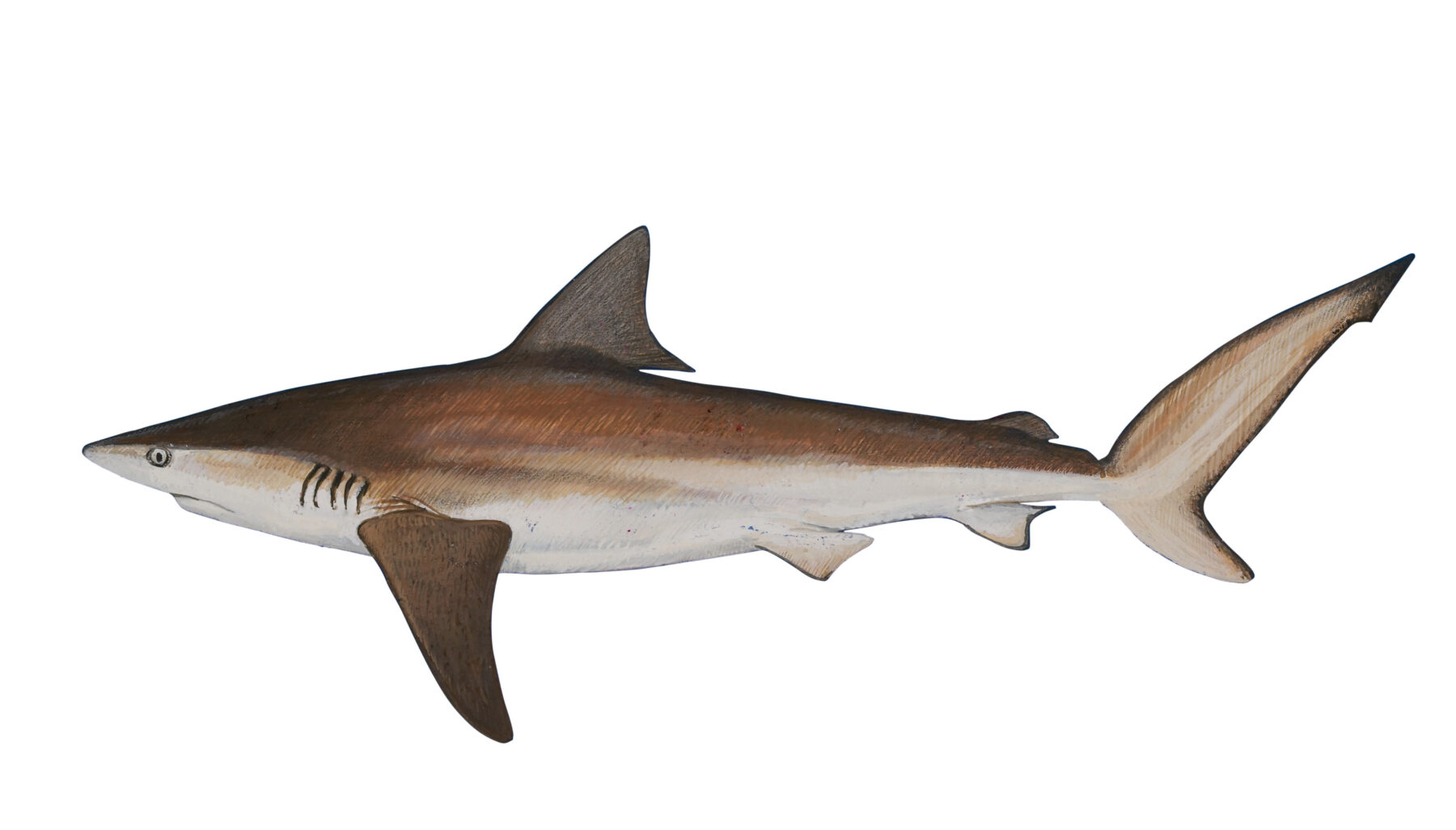

Bronze whaler

Carcharhinus brachyurus

IUCN status: near threatened

Size: up to 3m

This species is potentially dangerous to humans and often occurs in pairs. It feeds on fish, squid and the occasional sea snake throughout its range, which takes in southern Australia from Jurien Bay, WA, to Coffs Harbour, NSW.

Great hammerhead

Sphyrna mokarran

IUCN status: endangered

Size: up to 6m

Easily identified by its broad, flat head, this large shark is found in northern Australian waters from Sydney to the Houtman Abrolhos, WA. While few attacks on humans have been recorded, the great hammerhead is considered dangerous. It feeds on fish, other sharks, crustaceans and cephalopods, but is best known for its appetite for rays, which it pins to the sea floor with its head before taking a bite out of the ray’s wing, incapacitating it.

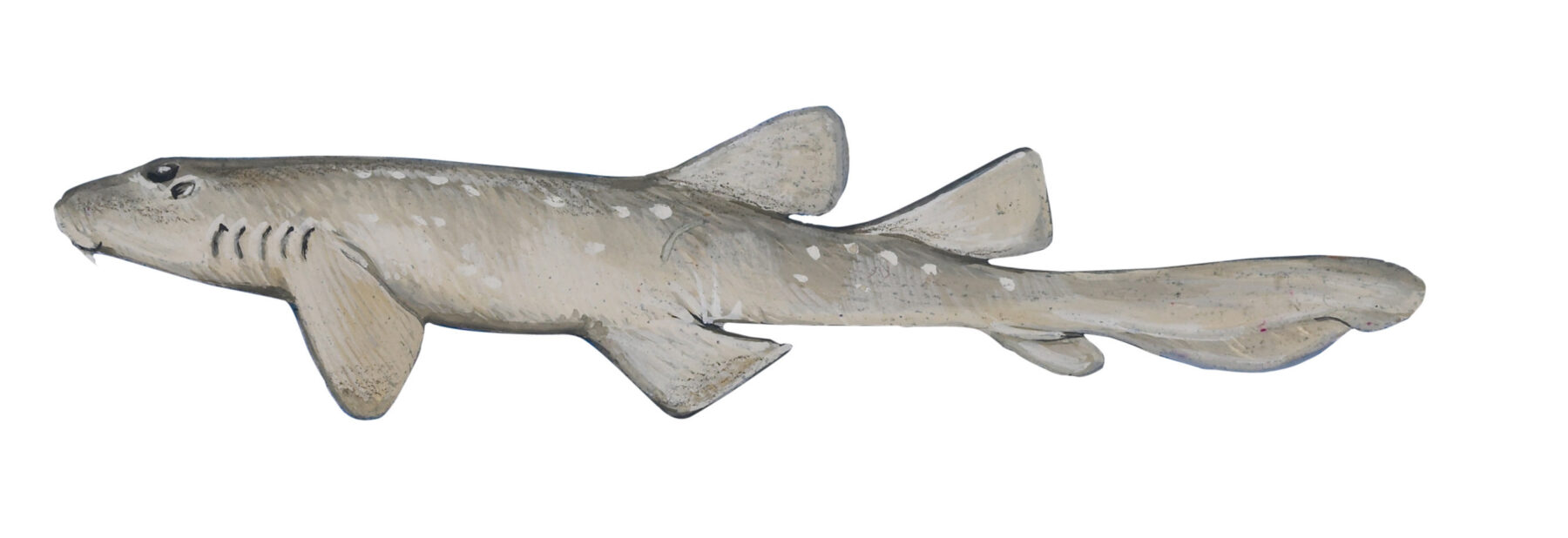

Blind shark

Brachaelurus waddi

IUCN status: least concern

Size: up to 1.2m

Named for its habit of closing its eyes when caught by fishermen, this shark is endemic to intertidal zones along eastern Australia, Mooloolaba, Queensland, and Jervis Bay, NSW. This relatively common and hardy species is not intentionally targeted by commerical fishermen or anglers, and isn’t common as bycatch, reef invertebrates and small fish.

Pygmy shark

Euprotomicrus bispinatus

IUCN status: least concern

Size: up to 27cm

Black with pale fins, an underslung jaw and a luminescent belly, the pygmy shark measures less than 30cm when fully grown and is harmless to humans. An open-ocean dweller, it spends its daylight hours in deep water (to depths of 1520m) and migrates after sunset to the surface in pursuit of bony fish, cephalopods and crustaceans. In Australian waters, it’s found in tropical and warm-temperate seas from Perth to Rowley Shoals, west of Broome, WA.