0/3

This month in

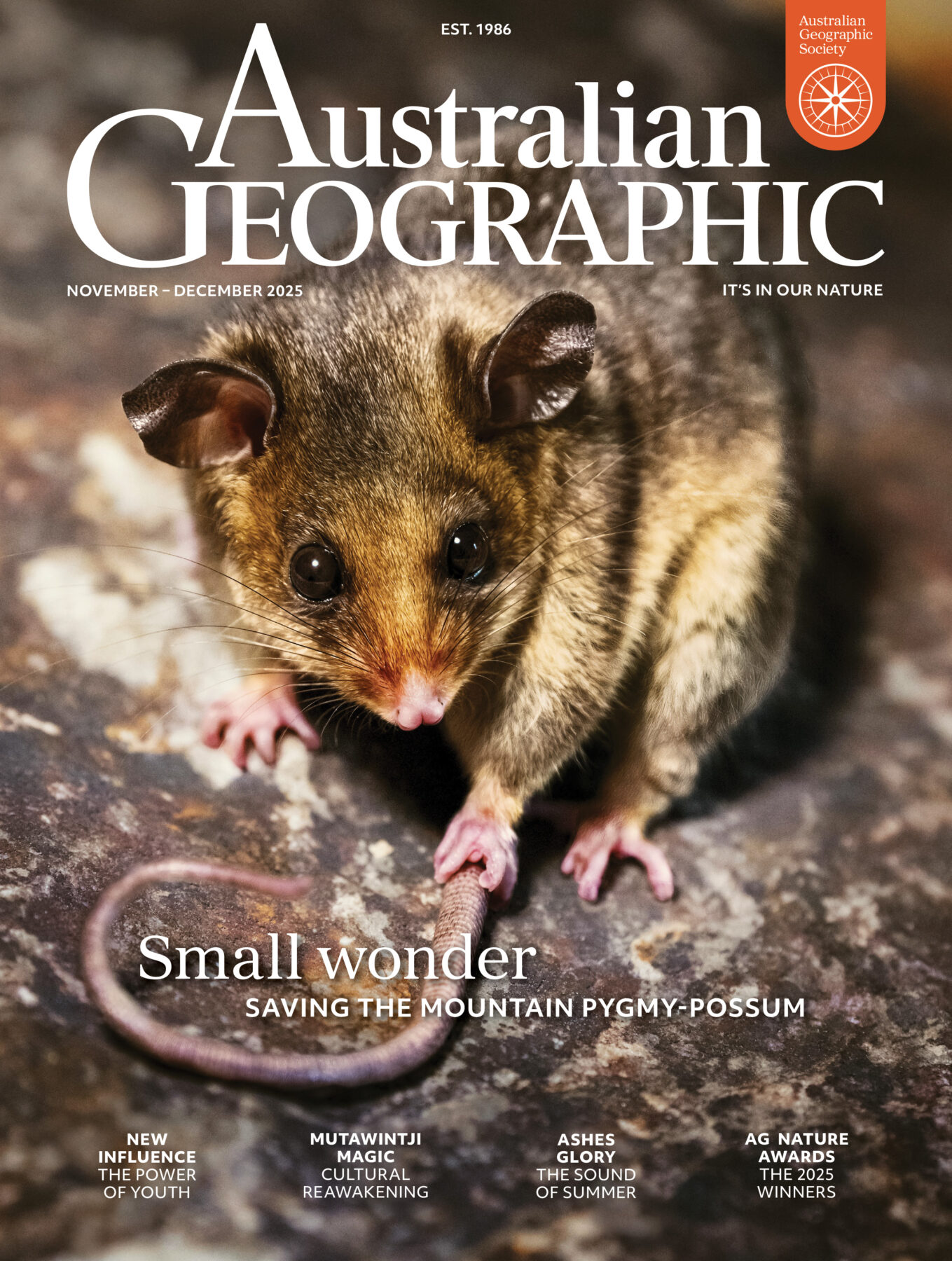

Australian Geographic

Delve into the latest issue of our award-winning magazine.

Subscribe to magazineDiscover the world of Australian Geographic

AG Adventure

Get all your outdoor inspiration here – adventures, destinations, gear tests and expert advice.

Discover more

AG Society

Australian Geographic contributes 100% of its profits to its registered charity, the Australian Geographic Society, to fund its conservation and sustainability grants.

Discover more

AG Travel

At Australian Geographic Travel our objective is to inspire love and care for Australia: our nature, our people, our places!

Discover moreDive into a world of Australian wildlife, science and adventure

Browse all videosAustralian Geographic Shop

Browse our online store for gifts, gadgets, puzzles, books and more

Talking Australia podcast

Talking Australia shares the stories of Australia’s most inspiring adventurers, conservationists and wildlife experts. Listen as they take you on a journey around this magnificent country and beyond.