‘Wild’ dingo characteristics are genetically dominant

RESEARCHERS STUDYING the skull shapes of dingoes, hybrids and domestic dogs have discovered that when cross-breeding occurs, the dingo skull shape remains dominant.

Since their arrival on Australia’s mainland more than 3000 years ago, dingoes (Canis lupus dingo) have adapted to a huge variety of habitats, and become somewhat of an Australian icon.

However, following European colonisation, much of its habitat became agricultural and pastoral lands, and with that came increased interaction with domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) – introduced by the settlers – leading to hybridisation between the two subspecies.

Considered one of the biggest threats to the species as a whole, changes in the skull shape of dingoes toward that of domestic dogs could impact their ability to hunt – having significant repercussions not only for dingoes, but the unique Australian ecosystems to which they belong.

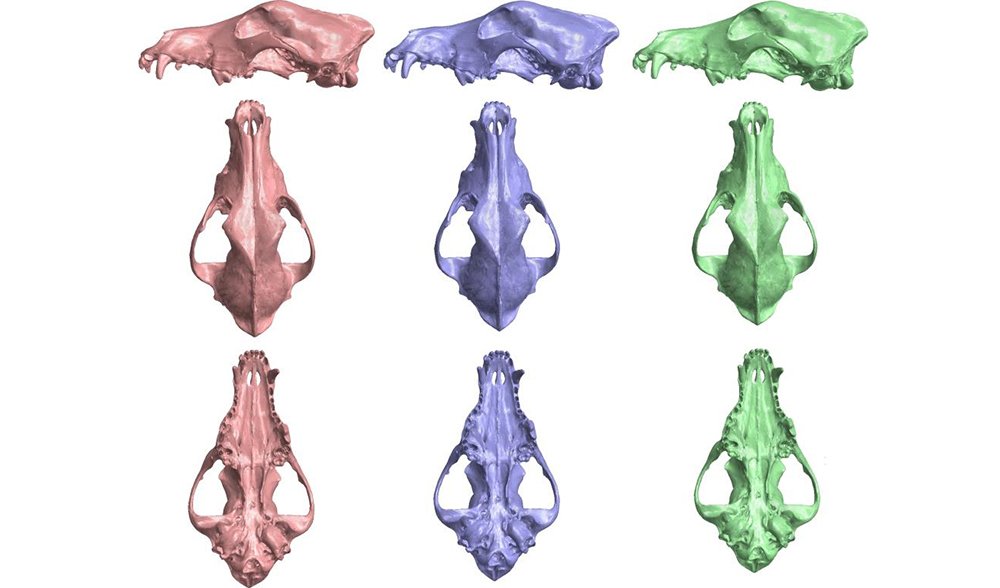

Spot the difference: The pink skull is the dingo, the purple skull is the hybrid and the green skull is the wild dog breed. (Image: W.C.H. Parr)

“Dingoes play an important role in our ecology,” explained Dr Michael Letnic, associate professor in the School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of New South Wales.

“They’re the largest predator that we have in Australia and they benefit ecosystems on the whole because they suppress numbers of introduced foxes and feral cats.

“So even though they’re predators themselves, dingoes benefit small animals that are especially vulnerable to predation by foxes and cats,” he said.

Specific points on the skulls were used in the statistical analysis of the shape. (Image: W.C.H. Parr)

A strong gene pool

Michael – along with Dr William Parr, Dr Laura Wilson and Dr Mathew Crowther – used CT scanners to create 3D models of skulls from animals with known genetic backgrounds, before using 3D shape analysis to determine what group each skull belonged to – pure dingo, hybrid or domestic dog.

But what they found was that the skulls of hybrids were indiscernible from those of pure dingoes.

“What we found was a strong convergence on the dingo-type shape,” Michael said.

“There was a strong tendency for animals to look like dingoes regardless of whether they were a pure dingo or had been cross-bred.”

Researchers believe selective breeding of domestic dogs for aesthetics, usefulness or maintaining a breed – often targeting recessive characteristics – has narrowed the domestic dog breeds’ gene pools.

Arriving in Australia more than 3000 years ago, dingoes have faced persecution since European settlement for killing livestock. (Image: Bradley Smith)

“Those characteristics becoming evident in domestic dogs – things like floppy ears or particular shapes of dogs or hair colours – often is a result of people targeting for specific mutations that are often deleterious – they’re not things that are advantageous in the wild,” Michael explained.

“Dingoes have been living in the wild for thousands of years, and they’ve had a very strong selection for the characteristics that are required for animals to survive in the wild,” he said. “Those wild-type characteristic also appear to be genetically dominant.”

Further research into the characteristics of hybrids – including their behaviour – may be conducted in the future, but for now, it looks like dingoes are here to stay.

RELATED CONTENT

- Dingoes declared a separate species

- Dingo culls cause more harm than good

- Austropalaeo: Dawn of the dingo

- Dingoes skilled at reading human gestures

- Dingoes cleared of mainland extinctions

- VIDEO: Conserving pure dingoes at Secret Creek