Researchers to search for ancient ‘extinct’ echidna

A TEAM OF Australian researchers is planning to search for the long-beaked echidna in rugged pockets of the Kimberley in Western Australia.

The expedition, led by ecologist Professor David Watson from Charles Sturt University, will deploy a trained sniffer dog, motion-triggered cameras and local volunteers to look for the long-beaked echidna (Zaglossus bruijnii) in isolated areas never before explored by scientists.

“There’s a very, very small chance they’re still there. We’ve got the technology and the skills, so if they’re there, we will find them,” said David.

‘Beakie’ thought extinct in Australia since the Ice Age

The world’s oldest remaining mammal species, the enigmatic long-beaked echidna is only known to inhabit the lush rainforests of Papua New Guinea, where it is critically endangered.

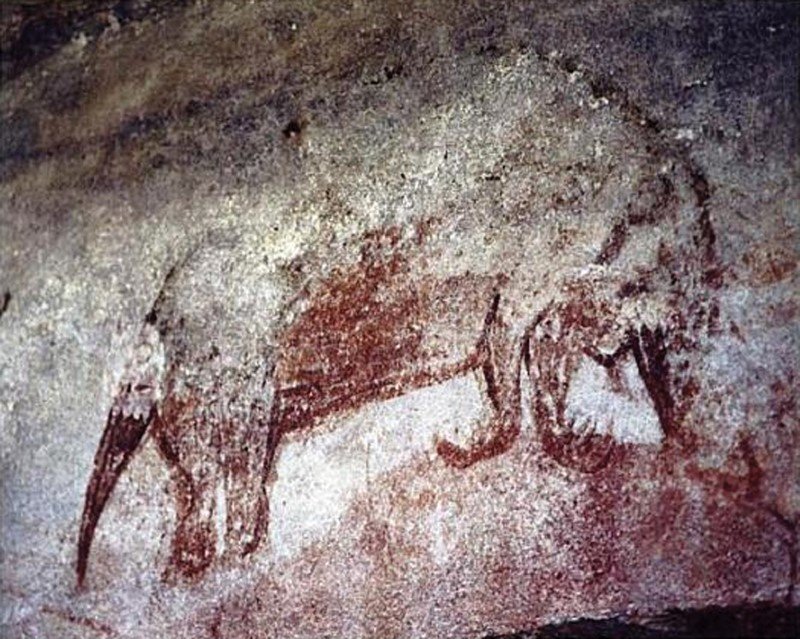

Fossil records and Aboriginal rock art show the ‘beakie’ once lived in Australia, but scientists previously believed it became extinct during the last Ice Age 10,000 years ago.

Photograph of an Aboriginal rock art illustration from Arnhem Land depicting the long-beaked echidna, which researchers believe may have survived in WA’s remote Kimberley region longer than previously thought. (Image: Helgen KM, Portela Miguez R, Kohen J, Helgen L/Wikimedia (CC-BY-3.0)

But in 2009, a surprise discovery suggested the long-beaked echidna had in fact survived in Australia until recently.

Professor Kristofer Helgen, a renowned mammologist based at the University of Adelaide, noticed a specimen at the Natural History Museum, London, that had been collected in 1901 near Mount Anderson in the Kimberley.

Subsequent detective work confirmed the authenticity of the specimen. “The conclusion was that yes, at the turn of the century, there was at least one long-beaked echidna in the Top End,” said David.

Science writer and biologist, Adrian Burton, was also captivated by the mysterious finding. “After that article was published I wondered whether anyone might one day be lucky enough to find this creature,” he said, “And then I thought… why don’t I go look for it?”

He mentioned the idea in passing to David, who was immediately excited, and began assembling the expedition team.

“The other echidna”

The search will begin in September this year, with a three-week field trip to consult with local communities, install cameras, and select potential survey sites.

Consultation of the traditional Aboriginal owners is essential, said David. Their oral histories record the existence of the mysterious long-beaked echidna. “The Miriwoong Gadjerong and other local communities recognise two species of echidna: the common short-beaked echidna found across Australia, and ‘the other one’,” he said.

“They’re very different critters,” David explained. “The long-beaked echidnas are two to three times heavier, hairier and stronger. They eat a variety of large rainforest insects by probing with their long snout.”

David said the long-beaked echidnas were “very rarely seen” in their known home of Papua New Guinea. “It’s a bit like night parrot stuff – there’s only a handful of observations and we’re piecing together fragments,” he explained.

Professor David Watson expects the expedition will uncover new species, regardless of whether the mysterious long-beaked echidna is found. (Image: supplied)

“Echidna turd-sniffing dog at the ready”

After laying the groundwork, the team will return in September 2018 to undertake the on-the-ground survey, cataloguing species while keeping an eye out for ‘beakie’.

“The expedition will take an inventory of what lives in this unexplored region,” said Adrian. “Our beakie is the flagship.”

David stressed that the aim of the expedition is not to capture a long-beaked echidna. “We’re concerned about welfare and the last thing we want to do is add to their burden. The long-beaked echidna will ideally never know we were there,” he said.

Instead, the team is hoping remote cameras and DNA samples from scat will provide the evidence they’re looking for. A four-legged, poo-sniffing expedition member has been recruited especially for the scat-seeking job.

“Jim Shields has an echidna turd-sniffing dog at the ready,” said David, who went on to explain that the dog is being trained with bona fide long-beaked echidna poop. “There’s one big old beakie fella at Taronga who is not on display. Any and all turds produced by him will be packaged and sent to Jim,” he added.

“You go to the Kimberley, you find new species…”

Even if the team doesn’t find the long-beaked echidna, the expedition is expected to produce valuable scientific findings – especially in the wake of the cane-toad invasion surging across northern Australia.

“We know cane toads are only 200km away. We must conduct this survey before they get there so we know what and where native fauna are in the region, and how we can protect them in the coming years if they are to survive this toxic wave,” David said, adding, “There’s no doubt we’ll find undescribed species. You go to the Kimberley, you find new species… that’s how it works!”

Adrian is excited for the scientific and communication opportunities too. “I believe there is something fundamentally important in simply knowing what we share our rock in space with. Even if beakie eludes us, we will come back with a pile of science. I think that’s well worth slapping on some sunscreen for,” he said.

The team will provide live updates from the field via social media so the public can share in the adventure.

READ MORE:

- Scientists to search for Tassie tigers in Queensland

- Sighting of a lifetime: night parrots found in WA