Western Australia is home to ‘Australia’s Jurassic Park’

The Dampier Peninsula in Western Australia is well-known for its white-gold beaches, ochre-rich cliffs and sprawling tableland. But the sandstone rocks beneath the swelling tides tell a different story. If you found yourself strolling along the coast 130 million years ago, you would be surrounded by massive herds of dinosaurs, from giant long-necked plant-eaters to three-toed carnivores.

The 25km stretch of coastline north of Broome is home to thousands of dinosaur tracks belonging to more than 20 different groups, making it the most diverse track site in the world.

Steve Salisbury, a palaeontologist from the University of Queensland, say the the tracks offer a rare glimpse into the dinosaurs that roamed the area during the Early Cretaceous Period.

“It’s such a magical place – Australia’s own Jurassic Park, in a spectacular wilderness setting,” says Salisbury.

Unveiling an ancient world

Back in 2009, Western Australia Premier Colin Barnett told The Age that Walmadany was an “unremarkable beach”, which was nothing like the Kimberley “that Qantas uses for its ads”. The comments came in the wake of a looming proposal to build a billion-dollar liquid natural gas processing hub in the area.

Alarmed by the prospect, the Goolarabooloo community contacted Salisbury to come and take a closer look at the dinosaur trackways they had held sacred for thousands of years.

While Salisbury had also known about the tracks for some time, he expected that there would be around half a dozen different tracks dotting the landscape.

But within the first week of setting foot on the dinosaur-trampled rock platforms, he and his team of researchers, local dinosaur-tracking enthusiasts and traditional custodians identified 10 unique tracks.

“It was a bit overwhelming,” reflects Salisbury. “Often when there are a lot of tracks, they are usually from one or two different dinosaurs. But to have so many different types was really spectacular.”

To Salisbury, it was already clear that the coastline was far from your average white sandy beach. Instead, the lumpy rock platforms were once the ‘Cretaceous equivalent of the Serengeti’ where herds of massive dinosaurs crossed muddy ground.

The race against time

With the spectre of the gas project hovering, Salisbury and his team scrambled to document the dinosaur tracks as systematically as possible. They spent around 400 hours photographing, measuring and analysing the 130-million year old prints in the face of messy political tensions, blockaded areas and being stalked by security guards from resource companies.

“We needed the world to see what was at stake,” says Phillip Roe, Gooloarabooloo Law Boss, who assisted Salisbury on the project.

Over the next six years, the team uncovered a record-breaking 21 different types of dinosaur tracks. The findings were published earlier this year in the 2016 Memoir of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

“There was this huge sense of responsibility to document the tracks so that we could conserve them,” says Salisbury. “We had to do good science as fast as possible to help garner public support.”

The turning point came in 2011 when the coastline was listed as a National Heritage site. In 2013, the natural gas project was cancelled when Woodside Petroleum pulled out due to economic constraints.

The stomping ground

During the Late Cretaceous period, the Dampier Peninsula was dominated by a vast sandy river that opened up into tidal deltas, brackish lagoons and estuaries. When the river flooded, a layer of silica-rich mud was deposited on top of the sand.

After the flood subsided, dinosaurs crossed the muddy plain to reach the other side, leaving behind the tracks that are seen today.

Out of the thousands of tracks embedded in the oyster-encrusted intertidal rocks, the team categorised 150 tracks into 21 distinct types. These track types belong to six dinosaur groups and are at least 15 million years older than the dinosaur fossils found in eastern Australia.

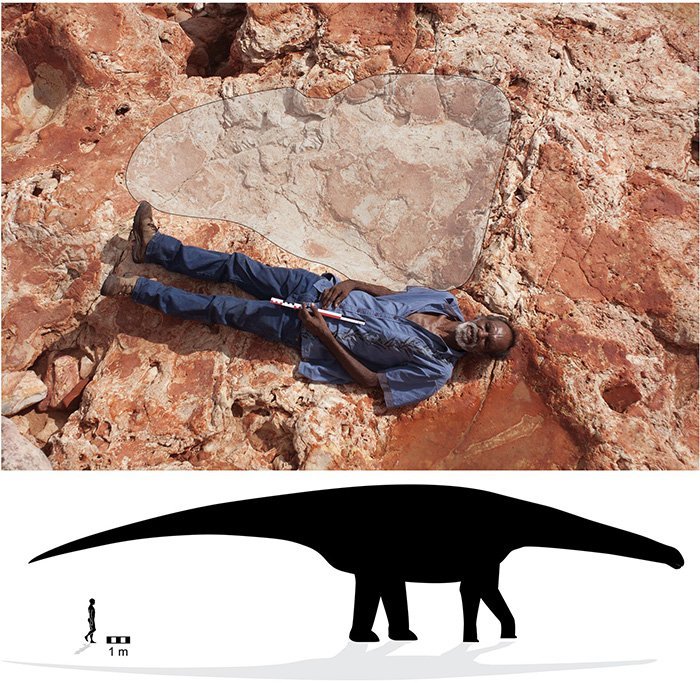

The most common track type belonged to massive long-necked sauropods, the group that includes the famous Brontosaurus excelsus. They appear as deep round imprints in the rocks with ancient mud circling the edges.

Some of these tracks measure up to almost two metres, making them the largest in the world. The huge prints dwarf the last dinosaur track record holder that was discovered in Mongolia last year, which measured 106cm.

Salisbury estimates that this giant herbivore had a hip height of up to five and a half metres, a size so staggering that the team initially overlooked the tracks because they didn’t believe that such a massive animal existed.

Walking among these lumbering giants were spiked, heavily-armoured thyreophorans, including ankylosaurs and stegosaurs.

“This is really cool, because there was no confirmed evidence of stegosaurs here in Australia until now,” says Salisbury.

Two-legged plant-eating ornithopods also made an appearance with tracks like Wintonopus latomorum, along with the three-toed meat eaters whose tracks are assigned to Megalosauropus broomensis.

Following Emu Man

The hordes of dinosaurs that shaped the coastline are also the cultural backbone of the Goolarabooloo people who have lived in the area for thousands of years.

The tracks are a thread in an intricate song cycle that extends 450km along the coast from Bunginygun (Cape Leveque) to Wabana (Cape Bossut).

Song cycles, also called ‘songlines’ or ‘dreaming tracks’ map out the physical and spiritual characteristics of country. They tell the story about the paths taken by creation beings who sang the landscape into existence, weaving in the traditional law into the animals, plants, stars and places.

One of the key figures in the song cycle of this area is Marala or ‘Emu Man’, the lawgiver who keeps the land in order.

“He gave country the rules we need to follow. How to behave, to keep things in balance,” says Roe.

Marala moved through the Song Cycle from south to north, leaving behind three-toed tracks and grooved impressions of his tail feathers when he sat down to create his law ground.

Today, those three-toed tracks are assigned to Megalosauropus broomensis and are seen as testimony of Marala’s journey as told in the Song Cycle.

The tracks appear and disappear with the changing tides and shifting sands, revealing knowledge to the people when they need it.

“It made it clear to us that removing these tracks from the area is very much the wrong thing to do, because it is a part of this area, part of that landscape,” says Salisbury.

Stepping into the future

The next steps for Salisbury and his team will involve mapping out and interpreting the tracks to gain a clearer picture of how the dinosaurs behaved.

“There are all these stories locked in the rocks that we need to try and unravel,” says Salisbury. “There’s still about 100 kilometres of coastline that may have tracks in it.”

The team are also hard at work developing conservation management strategies for the area with help of the Goolaraboolo people, and around Broome, Yawuru. Salisbury has helped establish the Dinosaur Coast Management Group to raise awareness of the site and its importance to traditional custodians.

“There’s amazing stuff on the beaches of Broome,” he says. “It’s not just a stepping stone to doing other things in the Kimberley.”