On Saturday 21 June 1930, four fishermen ran their boat ashore at Bellambi, just north of Wollongong, and scrambled onto the beach. They had just escaped the jaws of “a mammoth sea serpent”.

The Mail reported: ‘”A digger who had seen Gallipoli and Flanders at their worst, and who saw [the fishermen] when they landed, said he had never seen such terror in men’s faces in the battlefields of either.”

Two weeks later The Newcastle Morning Herald reported sightings of another sea monster off Scarborough, just up the coast from Bellambi: “It appeared to be at least 80ft long, like a huge eel, and at times raised a long neck in the air.”

Australian naturalist David Hearst resisted the ensuing serpent hysteria. He believed these sightings indeed bespoke a monster, but not the kind with a dragon’s head and a spined snake-like body of the like that prowl the edges of medieval maps.

He concluded that these sightings were in fact encounters with “Cuttlefish or giant Sea Squid … not any kind of real serpent, but the terrible gigantic Calamary.”

Richard Ellis, author of the 1998 book The Search for the Giant Squid, agrees with Hearst’s assessment. Analysing stories of sea serpents from the 14th century to the 1800s, Ellis argues that a giant squid’s arms trailing the surface of the ocean could resemble the coils of a snake, and that the pointed stabilising fins at the tip of its man-sized mantle could make for a snout through the eyes of a fisherman. A 10m long clubbed feeding tentacle lifted out of the water would look similar, too, to the iconic slender-necked silhouette we associate with the Loch Ness monster.

And so we find the source of the ocean’s most fearsome monsters, from the sea serpent to the kraken to the seven-headed hydra, all stemming from sightings of the mythological cephalopod that still bewilders and intrigues us to this day: the giant squid.

But the natural history of the giant squid is a history of dead, dying, regurgitated, pickled and preserved specimens. Ammonium ions in their cells make them float when they die, so our imaginings of the giant squid have mostly relied on limp carcasses with ratty pale flesh, as dull and inanimate as washed up cuttlebones.

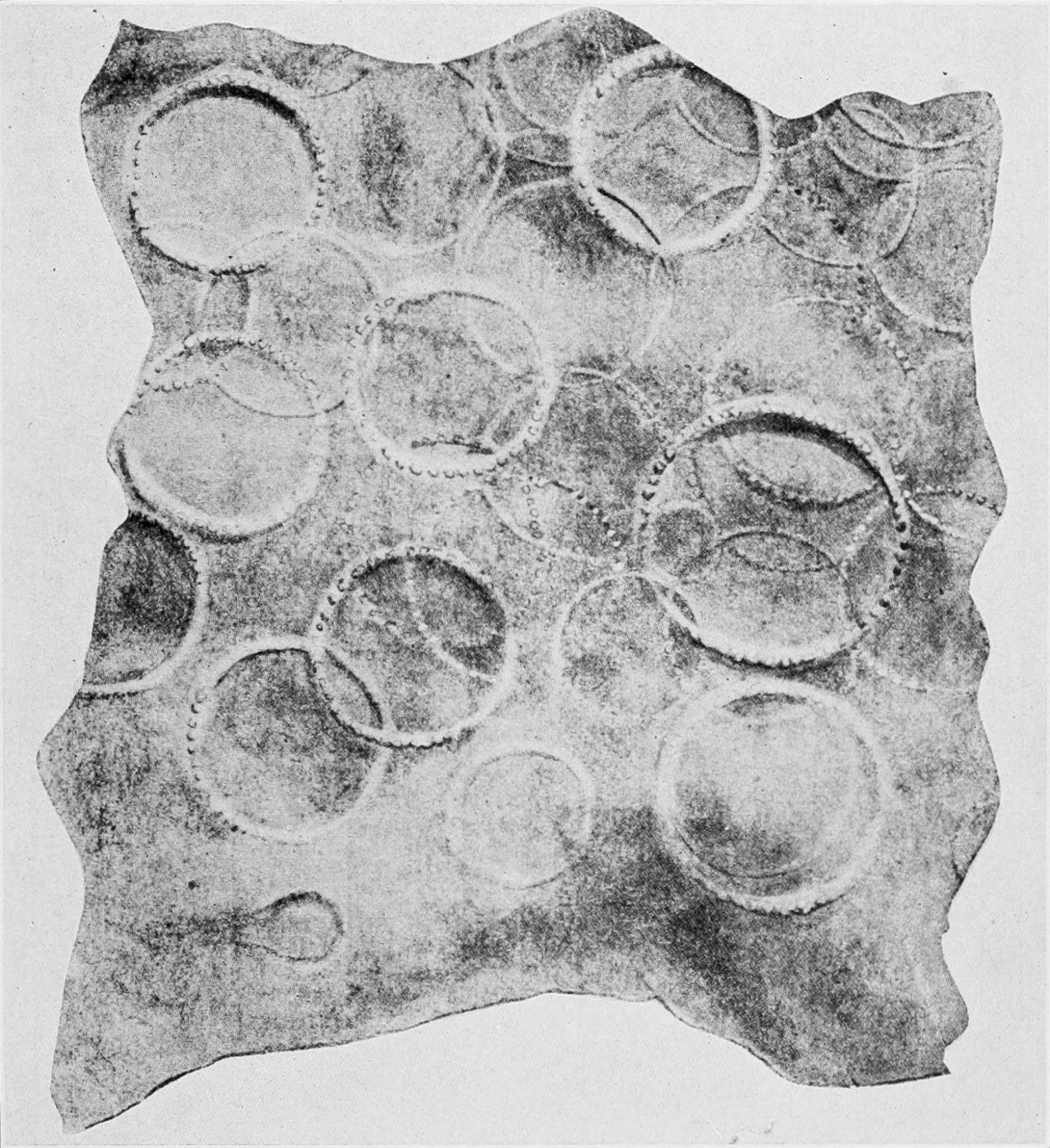

Hints of epic undersea battles came in the form of sucker marks that brand the bodies of sperm whales, and the giant macaw-like beaks salvaged from whales’ stomachs indicated the giants grew as large as 20m.

But these morbid clues only got us so far. We needed Architeuthis alive.

Sea monk, devilfish or chief of all squids?

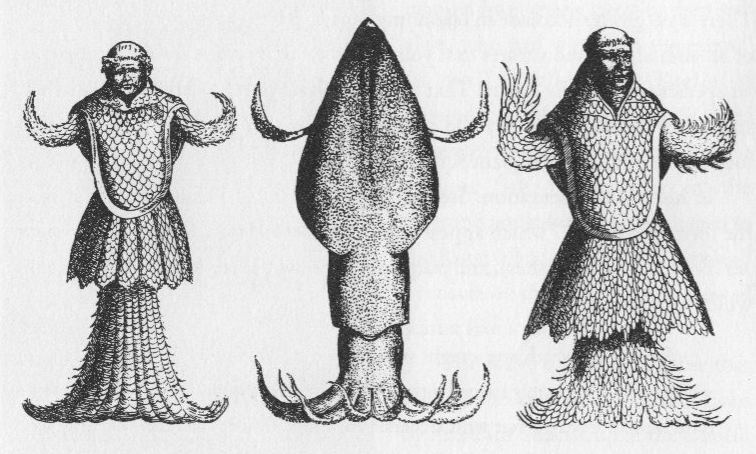

The giant squid was bequeathed its scientific name Architeuthis – ‘chief squid’ – by Danish zoologist Japetus Steenstrup in 1856. He had discovered records of Danish men catching a creature in 1550 that was described to the king as a ‘sea monk’, because it resembled the flowing scarlet robes of holy men. Steenstrup deduced that they were describing the pale pink mantle of a giant squid.

In 1861, a French warship approached an 18ft giant squid languishing on the surface of the ocean off the Canary Islands and pelted it with shells before it could give them the full kraken treatment. The body split in half as the crew hauled it aboard and they were left with a mess of arms and tentacles sprawled across the deck. This was a significant encounter that inspired the giant squid attack scene in Jules Vernes’ Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

Another notable encounter occurred in 1875, when a giant squid allegedly laid siege to a small fishing boat off the coast of St John’s in Newfoundland, Canada. According to one version of the events, the squid looped a tentacle around the gunwale of the boat. A small boy grabbed a tomahawk and hacked into the tentacle, severing it from the squid’s body.

They brought the 6m tentacle to shore and it became the first part of a giant squid formally examined on land. The Reverend in St John’s who came to possess the tentacle wrote: “I was now the possessor of one of the rarest curiosities in the whole animal kingdom – the veritable tentacle of the hitherto mythical devilfish, about whose existence naturalists had been disputing for centuries.”

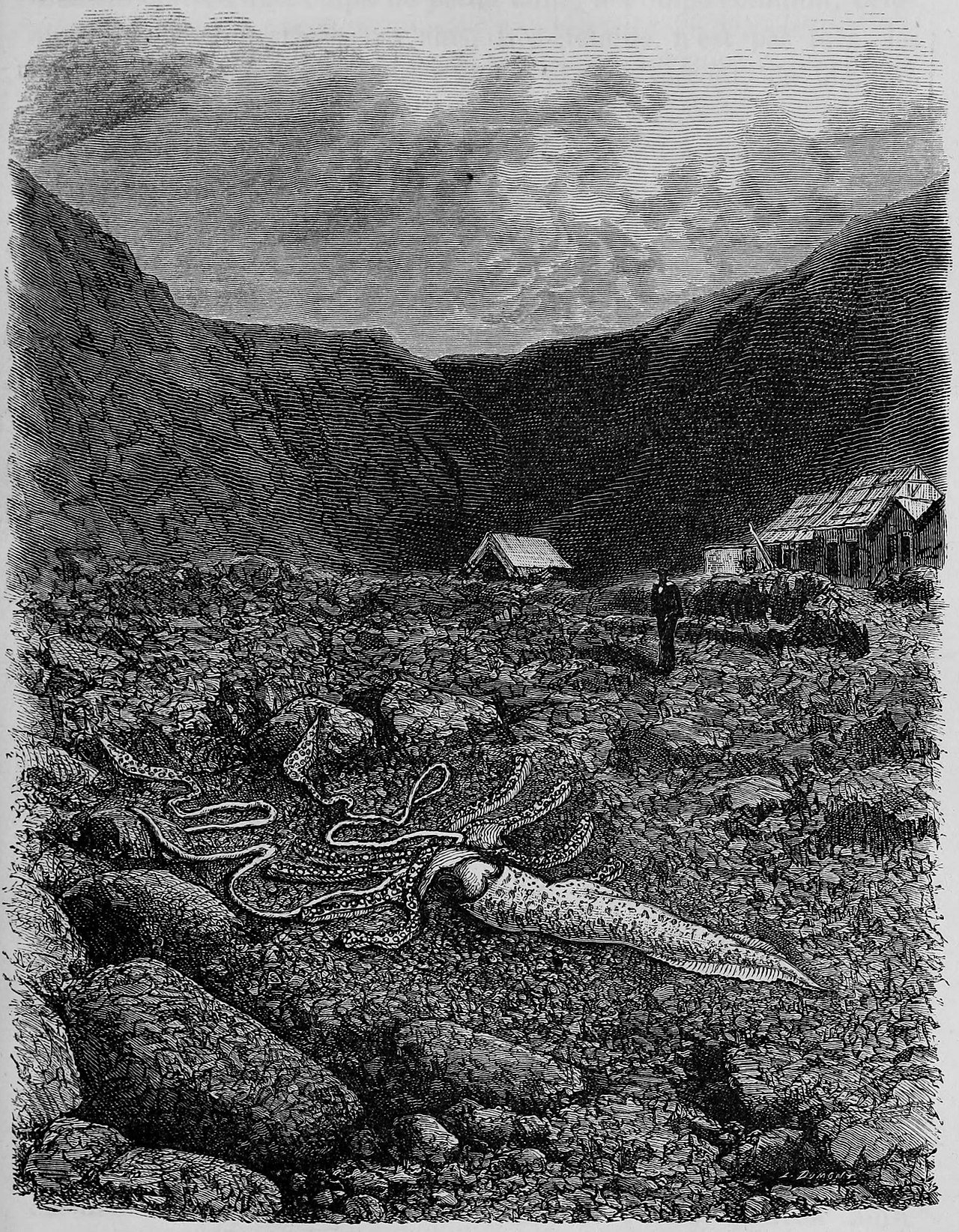

Little did the Reverend know it was the beginning of a time period Ellis describes as the ‘Architeuthis decade’. Between roughly 1870 and 1890, a record number of giant squid corpses washed up on the beaches of Newfoundland, accelerating our understanding of the squid’s anatomy.

Marine biologist Frederick Aldrich hypothesised that fluctuations in the Labrador current that pushed cold water closer to the Newfoundland coastline was responsible for bringing more squids into the area. He predicted another crop of strandings would occur throughout the 1960s – and when nine tentacled giants washed up between 1961 and ’68, it seemed he was proved right.

The antipodean Architeuthis decade

In the 1980s and 90s, Australia and New Zealand had their own boom of giant squid encounters.

In 1995 a 10m long female with a gashed mantle was found dead five kilometres off Mount Gambier. It had six-inch eyes (they can grow the size of basketballs) and carried eggs.

In 1996 three giant squid were caught around Tasmania and another four females were dragged from the waters of New Zealand by trawlers.

Scientists converged on New Zealand in 1997, like punters to a goldrush.

The Smithsonian’s Clyde Roper teamed up with National Geographic, planning to enlist Architeuthis’s arch nemesis, the sperm whale, to capture the first-ever images of the giant squid. They planned to affix a camera to a sperm whale’s back before it went plunging into the Kaikoura Canyon, off the east coast of New Zealand’s South Island, in search of its favourite food. It was to no avail.

In 2003, New Zealand scientist Dr Steve O’Shea tried a different approach. He filled his freezer with giant squid gonads, planning on blitzing the genitals into a paste that would attract a giant squid and elicit a sexual frenzy in front of the cameras. This idea, too, yielded no footage of the elusive squid.

And then, in 2012 – eureka! A human finally laid eyes on a giant squid in its natural habitat.

“Undoubtedly the most-significant moment was when Dr Tsunemi Kubodera observed the live animal from within a submersible, in situ, for an extended period of time, in waters off the Ogasawara Islands, Japan, in 2012,” says Steve. “Everything else pales in significance to this moment.”

Steve, Tsunemi and American oceanographer Dr Edith Widder had joined forces with different strategies for coaxing Architeuthis from the deepsea gloom and into the lights of a camera (a specialised device with an appropriately mythological name – Medusa). Steve opted for his pureed squid technique. Tsunemi used another whole squid as bait.

Edith went with the technique she became famous for engineering. She devised a lure based on a deep-sea jellyfish in distress. Some deep-sea jellies set off a spectacular light display when they are under attack, intended to attract a larger predator to dispatch of whatever animal is eating the jelly – a deep-sea version of a scream. Edith hoped that an artificial contraption that replicated this distress display – dubbed the ‘e-jelly’ – would attract Architeuthis to the Medusa.

All three methods would yield results, but Tsunemi was in the submersible when a giant squid first revealed itself to humanity. Out of the darkness materialised a creature worlds apart from the white, dead mounds of flesh found on Newfoundland beaches.

Muscular arms pinched together in a tight arrow before flaring open in a splay of tooth-rimmed suckers. The whole animal gleamed in ripples of bronze and burnished silver. Its two-storey body moved powerfully through the water but it nibbled the bait cautiously – a squid’s donut-shaped brain is wrapped around its esophagus, so too large a bite can inflict brain damage.

Here was Architeuthis in all its bizarre deep-sea glory. The footage lit up news stations globally when it was released and only ignited more questions from scientists and the public alike.

Architeuthis in capitvity?

“Despite the number of occasions that this animal has now been filmed or photographed when alive, there is still considerable debate as to its behavior,” says Steve.

“Some allege that it is an intelligent, fast-moving and active denizen of the deep, a scaled-up version of the Humboldt squid, propelling its tentacles out to catch prey at distance before withdrawing them to shred some hapless prey with its (often-cited razor-sharp) beak.

“Others, including myself, believe that it is a sluggish animal that as an adult is more an ambush predator and drifter, and not a very intelligent one at that, with a tendency to eat soft flesh much like someone with false teeth would do, because its beaks aren’t all that strong.”

And what of the creature’s lifespan?

While some estimate a giant squid lives to the age of five, Steve believes they lead much shorter lives (around a year and a half) and have a ‘phenomenal’ growth rate. He says their mantles could grow up to 2.75cm in a day.

Many of these uncertainties could be addressed by raising a squid in captivity. Steve, who has kept other species of deep-sea squid alive in captivity, says this is an entirely feasible exercise.

For decades he attempted to capture giant squid in its paralarval stage with the intent of raising Architeuthis in a tank. But finding the giant squid when they were no bigger than a fingernail was gruelling and expensive work. In 2001 Steve caught a handful of paralarval Archeteuthis using nets “soft as pantyhose”, but tragedy struck as he raced back to shore to deposit the squid into special aquariums he had made.

“When they all died on me years ago, I am afraid that it destroyed me,” he says.

But the dream of watching a giant squid twirl in an aquarium tank still lingers.

“I for one would dearly love to watch these animals grow, and would be a frequent paying visitor to watch, even if I wasn’t the one to finally achieve this. Everyone could enjoy it and experience the thrill of seeing this animal alive in person, rather than vicariously through the television screen.”

It was only recently discovered that 21 different species of giant squid all shared the same DNA and were in fact the same species – does that suggest their population plunged and then recovered from a genetic bottleneck? If they’re an animal affected by currents, as Frederick Alrich suggested, how is climate change affecting the Architeuthis? We know the male probably injects sperm directly into a female’s arms with a penis as long as its mantle, but what happens after that is mostly a mystery.

Richard Ellis wrote that the giant squid is “the last sea monster to be conquered”. If by ‘conquered’ he meant fully understood by science and demystified to humanity, then for now, Architeuthis has yet to be bested.