New genetic data reveals five distinct koala groups

Nestled in the eucalypt forests of the You Yangs, in Victoria’s East Gippsland, lives a small colony of 100 or so koalas.

To the untrained eye, they look pretty much the same as any other koala in Australia – grey fur, big button nose and the fuzziest of ears.

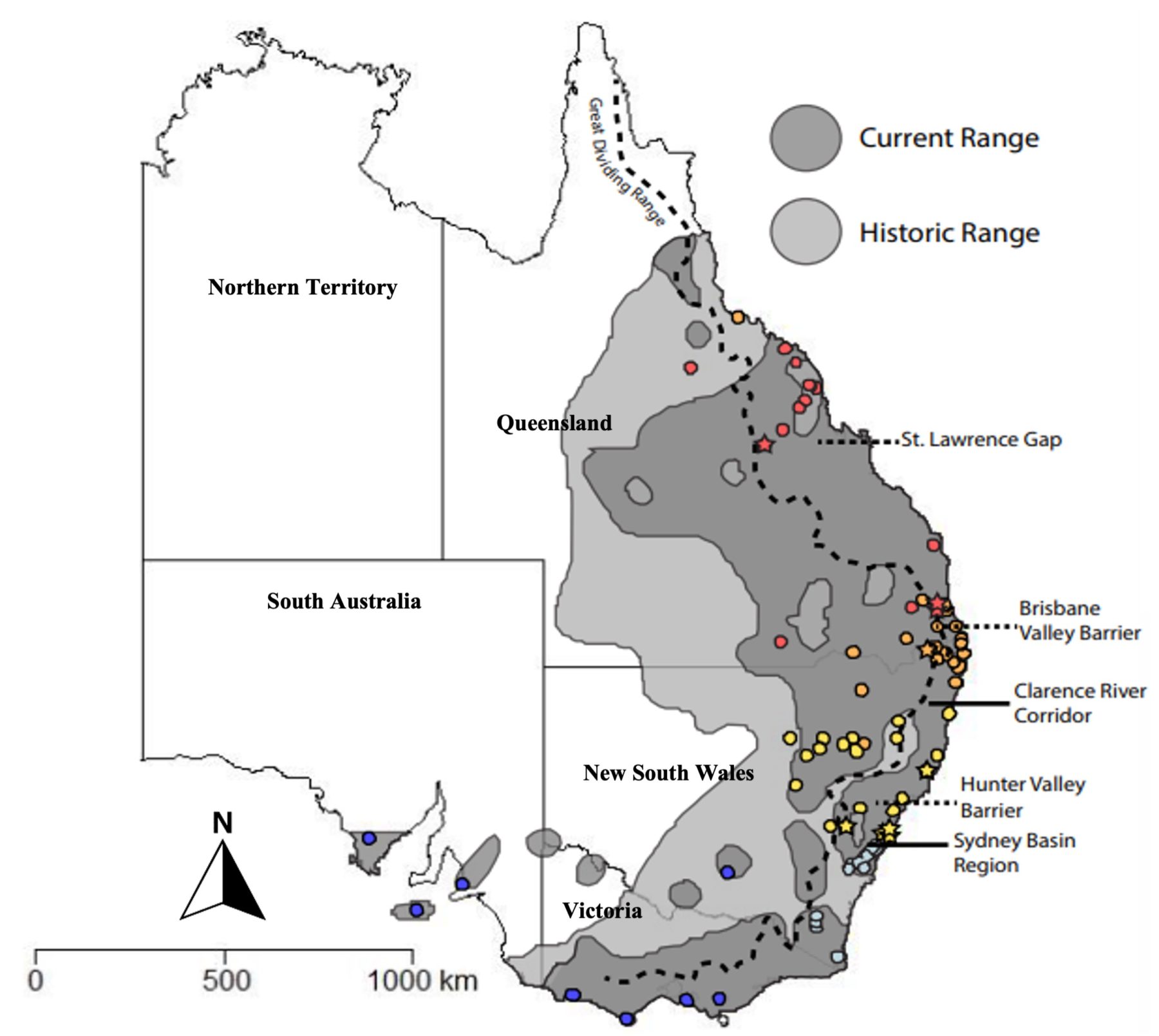

While the koala is one species, new research reveals that there are actually five distinctly different genetic groupings or population clusters across Australia’s east coast.

This discovery, published today in Molecular Ecology, was made by a group of scientists led by Australian Museum geneticist Dr Matthew Lott, using recent advances in the fields of genomics and bioinformatics on museum collections.

“We sequenced the protein coding gene regions, or ‘exons’, of 259 koalas from 92 locations across the species’ geographic range, representing the most comprehensive investigation of koala genetics to date,” says Dr Lott.

“While there are a few studies that have analysed a larger number of samples, our collection sites span nearly the entire modern distribution of the koala. By using museum specimens we’ve also been able to fill in some sampling gaps where it’s literally impossible to find koalas anymore.”

It is estimated these population clusters first diverged approximately 300,000–430,000 years ago, during a major climatic shift in the middle to late Pleistocene period.

Since then they have experienced periods of both connectivity and isolation as the Australian environment has changed over time.

Ensuring genetic diversity into the future

The loss of genetic diversity from small, fragmented koala populations has been shown to increase their risk of extinction due to both inbreeding and a reduced ability to adapt to rapid environmental change.

Australian Museum’s Terrestrial Vertebrates Principal Research Scientist, Dr Mark Eldridge, says as natural habitat continues to be lost, and dramatic events like natural disasters wipe out large numbers of koalas, the survival of the species is going to depend on maintaining gene flow between increasingly isolated populations.

“Therefore, the maintenance of genetic diversity by maintaining large, interconnected natural populations, or its augmentation through artificially assisted gene flow (i.e. wildlife translocations), is critical for conserving threatened koala populations in the face of existing and emerging threats,” says Dr Eldridge.

“There are currently no nationally recognised guidelines for koala translocations. However, the data from this research can be used to guide future translocation efforts.”

Dr Lott adds “our results are robust and wide-reaching, and can be used to help develop better, more evidence-based management paradigms, which will help mitigate koala decline.”

An initiative of the Australian Museum, this latest research was led by lead author Dr Matthew Lott, with the AM’s Dr Mark Eldridge, Dr Greta Frankham and Dr David Alquezar, along with Dr Rebecca Johnson from the Smithsonian Institution (formerly Director of AMRI), and researchers from the University of Sydney and the Australian National University.