Sharks have dominated our oceans for 450 million years, ancient predators that have evolved into a remarkable diversity of species. For an upcoming exhibition at the Australian Museum, a team of model makers from CDM:Studio, Perth, were commissioned to create 11 sharks. From extinct prehistoric sharks to mysterious deep-sea species, this studio combined traditional model making with 21st-century technology to produce shark models more hyper-realistic and detailed than ever before.

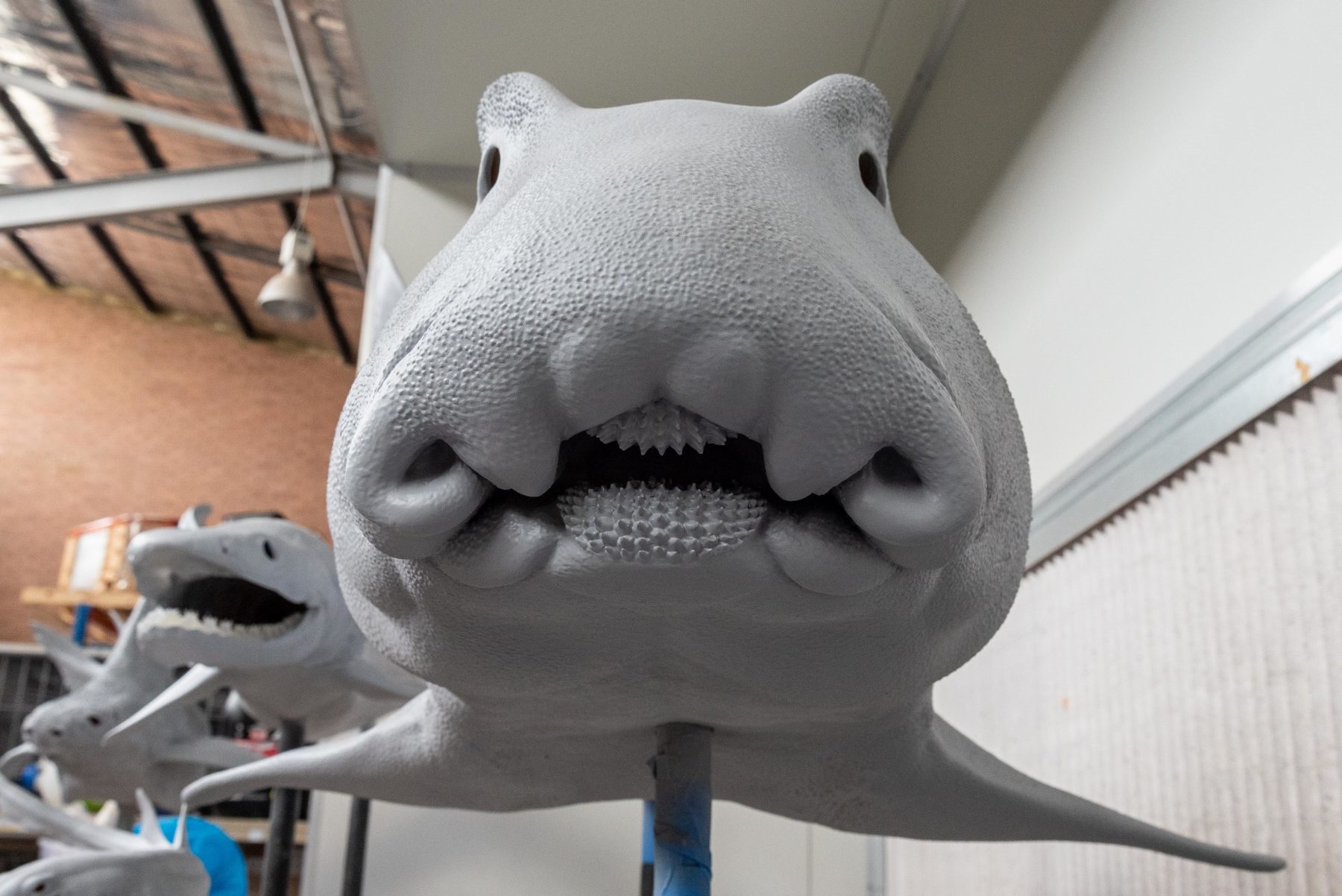

Daniel Browne, owner of CDM:Studio, has a background in sculpture. Referencing source material provided by the Australian Museum, Daniel and his team digitally sculpted the sharks in ZBrush, a software that combines 3D and 2.5D modelling, texturing and painting.

Transforming the source material into 3D models required a bit of detective work. According to Daniel, sharks are usually photographed from similar angles, a head-on shot or three-quarters profile that visually distorts their body proportions. He says it’s difficult to find images of modern-day sharks that haven’t been doctored or altered in some way.

Then there’s the helicoprion, an extinct species that lived 290–270 million years ago. The helicoprion’s “tooth whorls” – a spiral of fossilised teeth – have puzzled scientists since their discovery in 1899.

“The museum has done its homework, reviewing all the evidence to make our best assumption about what this shark might have looked like,” says Daniel.

Modern-day sharks can be equally as elusive. The goblin shark is a deep-sea species that has only been photographed a handful of times.

“Once we feel we’ve got the proportions correct, we hone in on the detail with further revisions, all the time flicking it back to the museum for approval,” says Daniel. “When we reach a point where we’re all happy, we get the digital sculpture, take it out of symmetry and pose it.”

Daniel and his team viewed the digital sculptures within a virtual gallery provided by the Australian Museum. Visualising the models hanging within the gallery space allowed the model makers to choose the best pose for each shark.

There’s another upside to using the ZBrush digital sculpting tool. Because it’s a digital asset, the software provided Daniel and his team with the model’s volume, allowing them to calculate weights for the engineering certificates in advance.

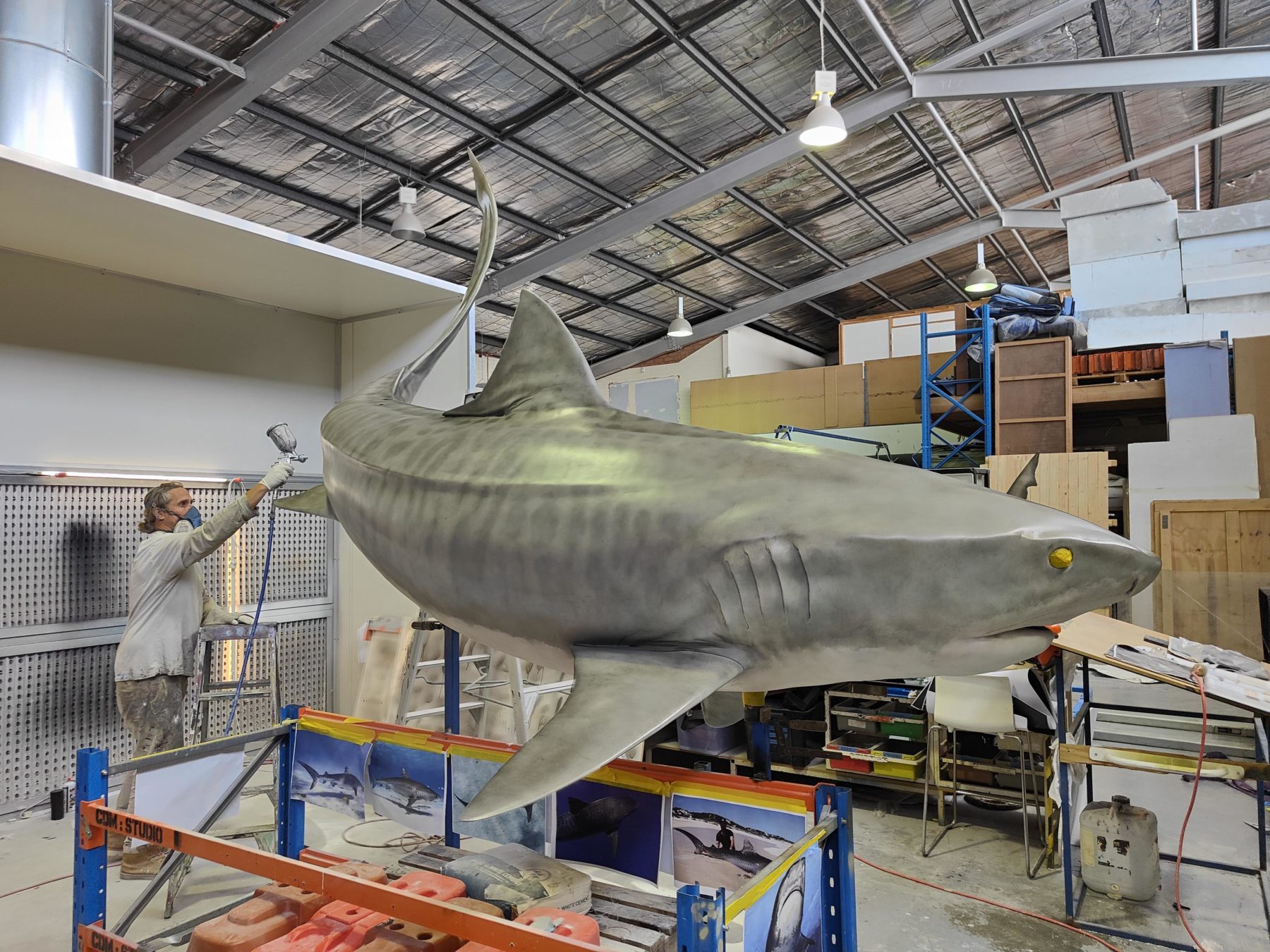

Once approved, the sharks were ready to be printed. The sharks were allocated to different fabrication pipelines, depending on their size. At 8m long, the whale shark was the largest model in the collection. Its sheer size made it impractical to 3D print, so it was CNC milled. The epaulette shark, the smallest model at 400mm, was SLA resin printed in one piece. Bigger models, such as the 4.5m long tiger shark, were digitally cut up and printed in sections.

“When you’ve got all those segments on the floor, it feels like [putting together] a giant toy,” Daniel says. “It’s fantastic.”

According the Jason Kongchouy, studio manager at CDM Studios, 3D printers have divided model makers within the industry. But he sees it as the future, believing everything has its place.

“3D printing just a tool that we use, in the same way you use as a hammer or a saw,” says Jason. “It’s a way for us to get to the end result. You don’t have to be a purist about it.”

Model making is physically exhausting, but 3D printing has compressed the labour-intensive process. That’s not to say it’s reduced their workload; instead, it’s freed them up so they can focus on other elements of the build.

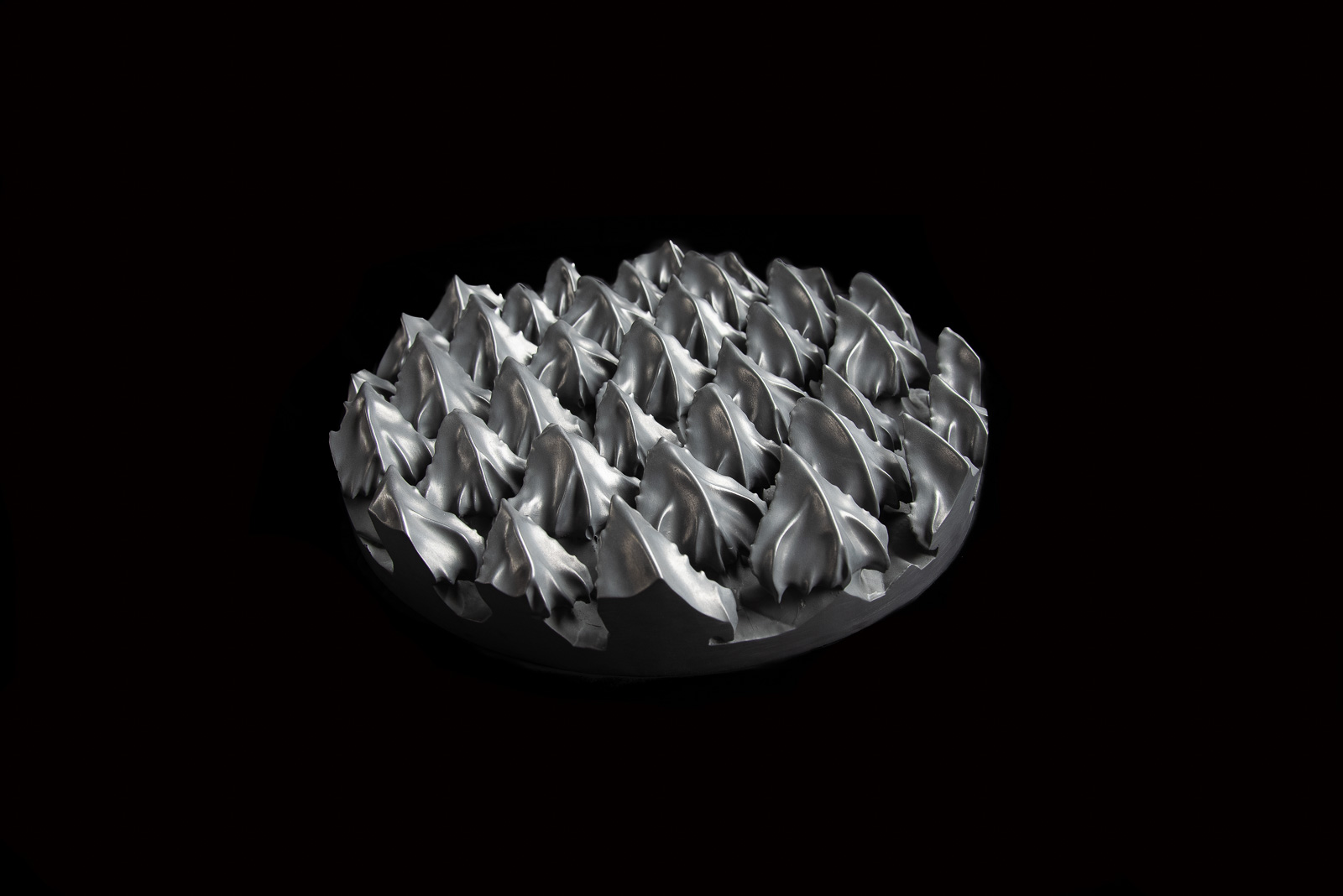

For example, the team at CDM were able to recreate shark skins. Shark skin is covered in flat, V-shaped scales called dermal denticles, whose rough texture decrease drag and allow the shark to swim faster and more quietly. With images of these shark sins at the micro level, Daniel and his team digitally sculpted the shark skins. Using these moulds, they poured aluminium powder with resin. Once it had set, the model makers took it out the mould and buffed the surface, giving the shark skin its distinctive grey-scale, metallic appearance.

“We’re not a print shop,” Daniel explains. “Printing is part of the process, but you can’t just ask a 3D printing company to make this for you. It’ll come off the 3D printer, it will look lovely, but it’s not a finished shark. The studio really shines because it’s backed up with 20 years of model-making experience before the printer came along.”

There’s another significant upside to these new technologies; it has created a cleaner and healthier work environment.

“One of the hangovers from the 70s was lots of fibreglass and polyester-based [materials],” says Daniel. “It’s that horrible smell of fibreglass resin, which is really quite offensive. Not having clay dust, toxic fumes and polystyrene everywhere makes a big difference. Anything you can do to remove those carcinogens and toxic fumes makes your workplace a healthier and better place to go to.”

Once the sharks have been 3D printed and assembled, they were assessed by an engineer to ensure it was safe and secure to hang in a public space. Then, the models were ready for painting.

According to Daniel and Jason, it’s an internal joke within the industry that painters receive most of the glory. But their importance cannot be underestimated; Daniel says he’s seen models made or broken depending on the quality of a paint job.

Similar to the digital sculpting process, the painting stage was accompanied by continuous debates, scrutinising source material and back-and-forth consultations with the museum. With its translucent skin, the prickly dogfish shark was one of the most difficult models to produce, as the team couldn’t agree what colour it was.

“Your perception of how things look in and out of the water is actually a bit off,” explains Daniel. “Sharks look greyer and bluer [in the ocean] because there’s no red spectrum, but when you take a shark out of the water, they’re brown.”

With some overlap, the fabrication process took Daniel and his team around four months to complete. The final stage was figuring out how to effectively package the sharks away for the museum.

“The museum doesn’t want to end up with 11 giant crates,” Daniel explains. “We ‘ying and yanged’ them for days on end, looking at the way they fitted together. Looking into these packing crates was like looking into a squashed-up aquarium.”

The Australian Museum’s Sharks exhibition opens 24 September.