Dr Karl explores the shapeshifting world of worm blobs

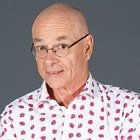

Dr Karl Kruszelnicki

Dr Karl Kruszelnicki

I was digging the compost pile into the garden bed recently when I noticed a reddish ball (about the size of a tennis ball) of entangled, shape-shifting worms.

Other critters will also form groups. Birds flock and fish school, giving the group a survival advantage over the individual solitary bird or fish.

Bees live in hives. If a big nasty hornet invades, they wrap their smaller bodies around it and beat their wings at very high speed. This kills the hornet by overheating it.

The semi-aquatic California blackworm is an expert at “blobbing”. It’s skinny and long, about 1mm in diameter and 20–40mm in length. It can form 3D soft blobs of up to about 500,000 worms. This worm blob can change its shape, and split and re-form, depending on its environment.

California blackworms love water. If you take them out of it, they’ll independently slither off by themselves, looking for water. If they fail, they’ll return to combine into a blob and then look for water as a group. The blob will survive 10 times longer than an individual worm.

Occasionally, the blob will manufacture and then stretch out a long skinny “arm” to search for water. It will retract this arm if none is found.

Scientists (especially those in artificial intelligence, physics and computational sciences) wanted to understand how animal grouping can sometimes spontaneously generate ‘intelligence’.

They used all kinds of mathematics, including: the Lennard-Jones Potential, which describes how atoms repel each other when they are too close but attract each other when they are too far apart; Brownian Motion – the jiggling of tiny particles in a blob of water, seen through a microscope; and more.

The main factor turned out to be a balance between two individual behaviours. These were the “stickiness” of individual worms (how firmly they stuck to each other) and how effective they were at travelling across the landscape.

Maybe the mosh pit at a concert is a human example of higher group organisation without central control. But certainly, there does seem to be strength – and intelligence – in numbers.