Indigenous fire management began more than 11,000 years ago, new research shows

Wildfire burns between 3.94 million and 5.19 million square kilometres of land every year worldwide. If that area were a single country, it would be the seventh largest in the world.

In Australia, most fire occurs in the vast tropical savannas of the country’s north. In new research published in Nature Geoscience, we show Indigenous management of fire in these regions began at least 11,000 years ago – and possibly as long as 40,000 years ago.

Fire and humans

In most parts of the planet, fire has always affected the carbon cycle, the distribution of plants, how ecosystems function, and biodiversity patterns more generally.

But climate change and other effects of human activity are making wildfires more common and more severe in many regions, often with catastrophic results. In Australia, fires have caused major economic, environmental and personal losses, most recently in the south of the country.

One likely reason for the increase of catastrophic fires in Australia is the end of Indigenous fire management after Europeans arrived. This change has caused a decline in biodiversity and the buildup of burnable material, or “fuel load”.

While southern fires have been particularly damaging in recent years, more than two-thirds of all Australia’s wildfires happen during the dry season in the tropical savannas of the north. These grasslands cover about 2 million square kilometres, or around a quarter of the country.

When Europeans first saw these tropical savannas, they believed they were seeing a “natural” environment. However, we now think these landscapes were maintained by Indigenous fire management (dubbed “firestick farming” in the 1960s).

Indigenous fire management is a complex process that involves strategically burning small areas throughout the dry season. In its absence, savannas have seen the kind of larger, higher-intensity fires occurring late in the dry season that likely existed before people, when lightning was the sole source of ignition.

We know fire was one of the main tools Indigenous people used to manipulate fuel loads, maintain vegetation and enhance biodiversity. We do not know the time frames over which the “natural” fire regime was transformed into one managed by humans.

A 150,000-year record of fire and climate

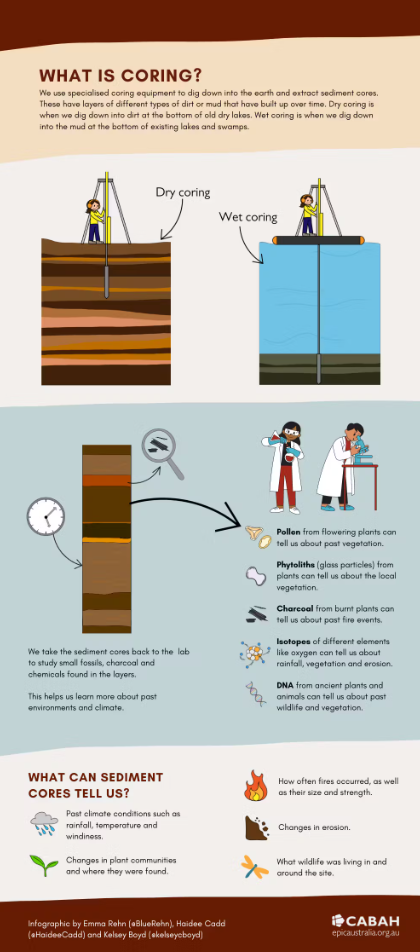

To understand this transformation better, we took an 18-metre core sample from sediment at Girraween Lagoon on the outskirts of Darwin. Using this sample, we developed detailed pollen records of vegetation and charcoal, and paired them with geochemical records of climate and fire to reveal how fire patterns have changed over the past 150,000 years.

Now surrounded by suburbs, Girraween Lagoon (the “Place of Flowers”) is a significant site to the Larrakia and Wulna peoples. It is also where the crocodile-attack scene in the movie Crocodile Dundee was filmed.

The lagoon was created after a sinkhole formed, and has contained permanent water ever since. The sediment core we took contains a unique 150,000-year record of environmental change in Australia’s northern savannas.

The core records revealed a dynamic, changing environment. The vegetation around Girraween Lagoon today has a tall and relatively dense tree canopy with a thick grass understory in the wet season.

However, during the last ice age 20,000–30,000 years ago, the site where Darwin sits now was more than 300 km from the coast due to the sea level dropping as the polar ice caps expanded. At that time, the lagoon shrank into its sinkhole and it was surrounded by open, grassy savanna with fewer, shorter trees.

Around 115,000 years ago, and again around 90,000 years ago, Australia was dotted with gigantic inland “megalakes”. At those times, the lagoon expanded into a large, shallow depression surrounded by lush monsoon forest, with almost no grass.

When human fire management began

The Girraween record is one of the few long-term climate records that covers the period before people arrived in Australia some 65,000 years ago, as well as after. This unique coverage provides us with the hard data indicating when the natural fire regime (infrequent, high-intensity fires) switched to a human-managed one (frequent, low-intensity fires).

The data show that by at least 11,000 years ago, as the climate began to resemble the modern climate that established itself after the last ice age, fires became more frequent but less intense.

Frequent, low-intensity fire is the hallmark of Indigenous fire regimes that were observed across northern Australia at European arrival. Our data also showed tantalising indications that this change from a natural to human-dominated fire regime occurred progressively from as early as 40,000 years ago, but it certainly did not occur instantaneously.

Unlocking Girraween’s secrets with modern scientific techniques has provided unprecedented insights into how the tropical savannas of Australia, and their attendant biodiversity, coevolved over millennia under this new Indigenous fire regime that reduced risk and increased resources.

The rapid change to a European fire regime – with large, intense fires occurring late in the dry season – abruptly regressed patterns to the pre-human norm. This ecosystem-scale shock altered a carefully nurtured biodiversity established over tens of thousands of years and simultaneously increased greenhouse gas emissions.

Reversing these dangerous trends in Australia’s tropical savanna requires re-establishing an Indigenous fire regime through projects such as the West Arnhem Land Fire Abatement managed by Indigenous land managers. By implication, the reintroduction of Indigenous land management in other parts of the world could help reduce the impacts of catastrophic fires and increase carbon sequestration in the future.

Cassandra Rowe, Research Fellow, James Cook University; Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Matthew Flinders Professor of Global Ecology and Models Theme Leader for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Flinders University, and Michael Bird, JCU Distinguished Professor, ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.