The little-known story of Australia’s convict women

AFTER A HARROWING six month voyage across the sea to the newly established British colony dubbed New Holland, convict women were either sold off for as little as the price of a bottle of rum or, if sent to Tasmania, then known as Van Diemen’s land, they were marched to the Cascades Female Factory — a damp distillery-cum-prison. Yet, despite their harsh treatment and dark experiences, the story of Australia’s convict women is ultimately one of triumph.

It’s estimated that 164,000 convicts were shipped to Australia between 1788 and 1868 under the British government’s new Transportation Act — a humane alternative to the death penalty. Approximately 25,000 of these convicts were women, charged with petty crimes such as stealing bread.

“Half the women landed in mainland Australia and half in Tasmania. Less than 2 per cent were violent felons. For crimes of poverty, they were typically sentenced to six months inside Newgate Prison, a six-month sea journey, seven to 10 years hard labour and exile for life. Clearly, the scope of their punishments far exceeded the scope of their crimes,” Deborah Swiss, the author of The Tin Ticket: The Heroic Journey of Australia’s Convict Women, tells Australian Geographic.

Deborah became fascinated with the stories of Australian convict women following a trip to Tasmania in 2004. “Their stories immediately captured my heart when I learned that if you were a working-class girl in London or Dublin in the 1800s you had two choices: enter prostitution, which was not a crime or steal food or clothing to be able to live another day,” Deborah says. “And so I began my six-year journey of researching and getting to know these remarkable female convicts.”

The journey to Australia

According to detailed ship journals, most of the female convicts had never even travelled on a rowboat, let alone a large ship before, so most experienced extreme sea sickness during the voyage. “The women were housed on the orlop deck, the lowest and the smelliest where they slept on wooden bunks that measured eighteen inches wide,” says Deborah.

Prior to their voyage to Australia, most of the women were incarcerated at Newgate Prison in London, which Deborah says was often referred to as “the prototype of hell”. It was here that the women came into contact with Elizabeth Gurney Fry, the first internationally known female social reformer.

Elizabeth gained the nickname the ‘Angel of Prisons’ for her work with female inmates at Newgate, who she regularly visited for over three decades.

“Inside Newgate, [Elizabeth] set up a school room where children imprisoned with their mothers could learn to read and write. She also taught the female convicts how to sew so that they would have a skill once freed in Australia,” says Deborah.

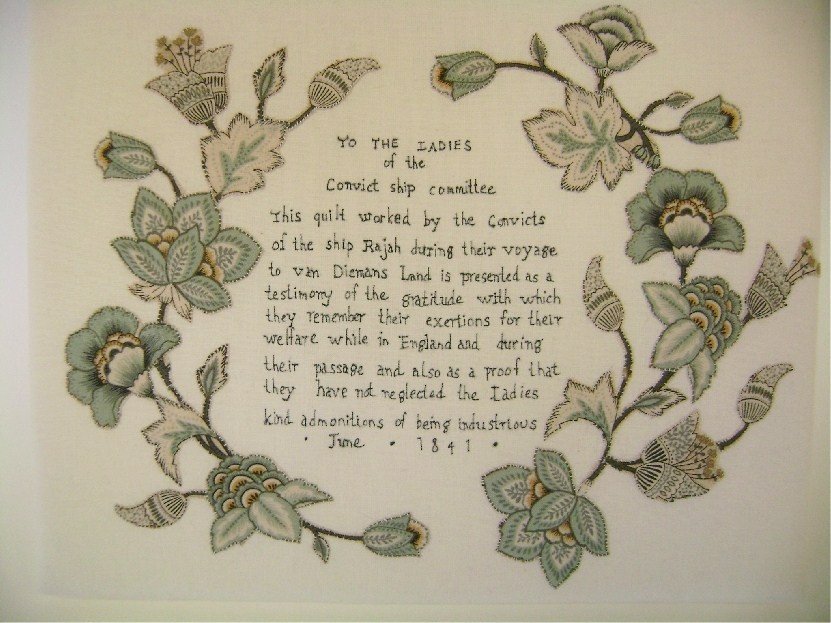

As they boarded the transport ships, Elizabeth and her volunteers gave each woman a bag that contained scraps of cloth, needles and thread. “Aboard ship the women could make a quilt which could later be sold in Australia for a few coins each.”

Only one convict-made quilt has survived the test of time. The Rajah Quilt – named for the ship aboard which the women prisoners and the materials for the quilt arrived in Hobart in 1841 – is now on display at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra.

Detail of the Rajah Quilt. (Image Credit: National Library of Australia Collection)

Life in Australia

Records of the lives of convict women living in Tasmania are well-preserved, while those documenting the lives of their counterparts in Sydney have been destroyed. According to the NSW Government many of the records were ordered to be destroyed by the military because they had no use, however some 20th century reports have led Deborah to believe that records may have been destroyed by convict descendants eager to wipe their past clean.

Based on arrest records, court transcripts, description lists, ships journals and newspaper accounts available to her, Deborah was able to create an accurate picture of Tasmanian women’s day-to-day lives.

“The newspapers in Van Diemen’s Land reported colourful escapades like the first female flash mob in 1840. They were known to sing and dance naked under a full moon, rebelliously removing their miserably scratchy shifts, which were purposely designed to be uncomfortable,” Deborah says.

And when it came to meeting their future partners, they were very creative.

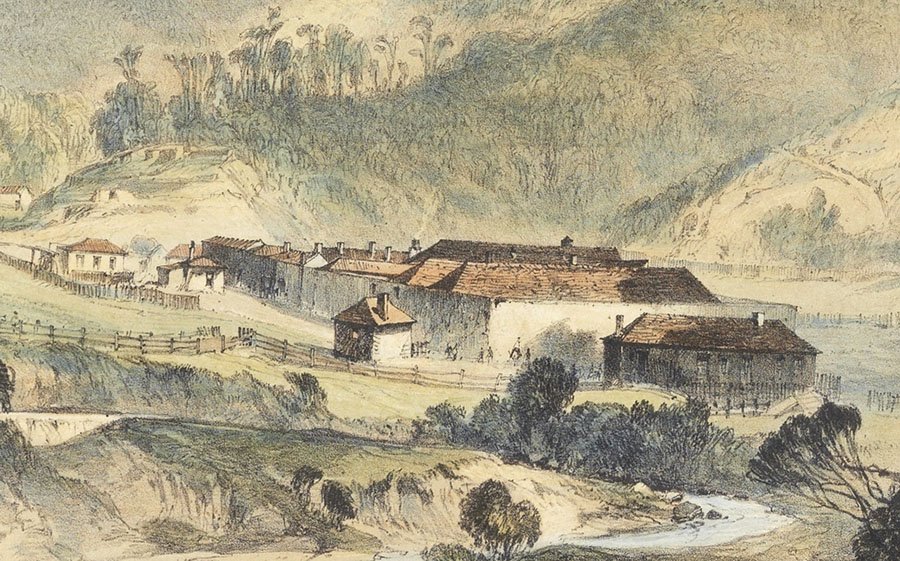

“At the Cascades Female Factory, one of the many rules was that the women were not allowed to speak to men. To find a way to communicate with prospective lovers, the women devised a scheme whereby they smuggled love letters inside chickens that were delivered to a corrupt warden.” Today, the Cascades Female Factory, located in Hobart, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and regularly holds exhibitions on the lives of the convict women housed there.

According to Deborah, the Transportation Act had a very clear economic motive. “The British wanted to beat the French to colonise Australia because it was rich in timber and flax. It was also social engineering in that the British government wanted to remove ‘the unsightly poor’ from their streets.

“The convict men were transported first and soon outnumbered women nine to one in Australia. You can’t have a colony without women so the female convicts were specifically targeted by the British government as ‘tamers and breeders’.”

The female factory from Proctor’s Quarry, Hobart. (Image Credit: John Skinner Prout)

Inspiring stories of convict women

During her research Deborah came across countless stories that she says exemplify the human spirit. “They were ordinary women who found the courage to become extraordinary because they had no other choice,” she says.

Deborah was particularly taken by the story of 12-year-old Agnes McMillan who was transported to Australia for stealing stockings.

“Agnes McMillan was left to fend for herself. Her story centres on how human beings find hope where none has the right to exist,” she says. “Her best friend and surrogate big sister Janet Houston was transported and imprisoned with Agnes. Surprisingly, The Tin Ticket also became a story about the power of women’s friendship to see us through the worst of times.”

Then there’s Ludlow Tedder, whose sad story has a bittersweet ending.

“As a widow and mother of four children she didn’t make enough to support them. She made the mistake of stealing eleven spoons and a bread basket that she pawned as a means to send her youngest child Arabella to school.

“For her crime, Ludlow received a 10-year sentence. Arabella was transported with her and Ludlow had to leave her other children behind who she would never see again. Once in Van Diemen’s Land, authorities took children away from their mothers and placed them in an orphanage because they wanted the children to be pure of their mother’s sins.

“By the time she was freed, Ludlow had cleverly saved enough money to essentially buy Arabella back from the orphanage. They left Tasmania for the goldfields in New South Wales and went on to become respected property owners.”

Changing perceptions

Many of the convict women’s descendants that Deborah interviewed for her book suffered from what they called the ‘convict stain’, which described the social ostracising that came with having convict heritage. However, Deborah says that revisionist history is starting to set the story straight.

“I was intrigued by the convict maids because women have been largely ignored in history as have the lives of the working class. I view the female convicts as heroic because they triumphed over tragedy as their lives transformed from desperation and injustice to freedom alongside a new start in a new land.

“The miracle of their story is that the vast majority of these women went on to become loving mothers and grandmothers. They became the founding mothers of modern Australia and 22 per cent of Australians today are descended from these remarkable convict women and men.”

READ MORE:

- The New Zealand convicts sent to Australia

- The story of Australia’s last convicts

- In pictures: love tokens from Australia’s convicts and soldiers