In May 2018 Murray Silvester made a confession: he’d killed hundreds of wedge-tailed eagles while working as a farmhand in Tubbut in Far East Gippsland, Victoria. Instructed by his boss, John Auer, Silvester laced animal carcasses with a concentrated pesticide and left them out for eagles to feed on and ingest the poison. Between October 2016 and April 2018, Silvester illegally killed more than 400 native eagles – and kept a detailed record of his actions.

At the time, I was working as a teacher not far from where this occurred. When the story broke, I was shocked and so too was the local community, and in response to the crimes and the court case that followed, there was also a huge outpouring of anger across the nation.

Wedge-tailed eagles (Aquila audax) are Australia’s largest birds of prey. These animals have historically had a tense relationship with pastoralists, who believed the birds were a threat to their lambs. For many decades, eagles were classed as vermin and legally trapped, shot or poisoned. Some states even had a bounty system that encouraged the killing of the birds. This changed in Victoria in 1975 when the state’s Wildlife Act provided protections for native animals.

Victoria’s Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning responded to Silvester’s confession by launching an investigation. Officers searched John Auer’s properties and discovered hundreds of eagle carcasses scattered across 2000ha. In September 2018, the Sale Magistrates’ Court issued Silvester a $2500 fine and sentenced him to 14 days in jail, making him the first person in Victoria to be jailed for wildlife-related crimes. Silvester’s boss was slapped with a $25,000 fine and ordered to complete 100 hours of unpaid community work.

A similar case

It’s now 2024 and I’m sitting in Shepparton Magistrates’ Court in northern Victoria, waiting to hear the verdict of a comparable crime. Dorothy Sloan initially faced 342 charges of animal cruelty, killing and possessing protected wildlife on her property in Violet Town in north-eastern Victoria. She’s spent the past three years defending her case in court.

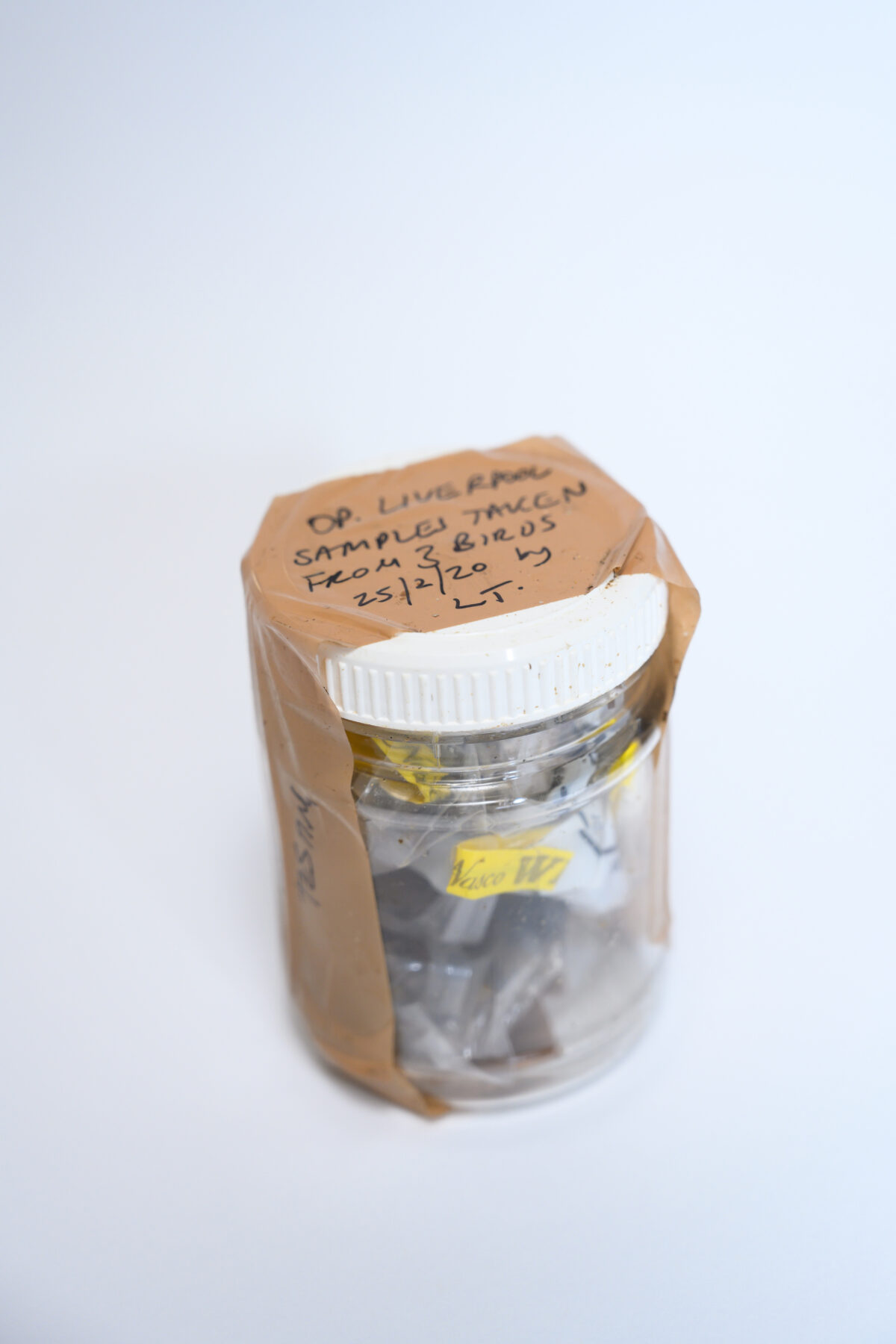

Sloan’s case bears many similarities to Silvester’s. Authorities found dozens of eagle carcasses on her property, including several stored inside her freezer with shotgun pellets still lodged inside. There’s also evidence she purchased large quantities of pesticide, which she used to bait and kill the eagles. And just like the Gippsland case, the community is upset and angry.

The Office of the Conservation Regulator (OCR) is the body tasked with investigating alleged breaches of environmental laws and, when necessary, taking enforcement action.

Greg Chant is the OCR’s manager of regulatory operation in the Hume region and has played a key role in both investigations. He says most investigations begin when a concerned member of the public makes a report. Perhaps they’ve noticed dead birds, seen someone laying baits or heard their neighbour talking about shooting eagles. It’s Greg’s job to assess these reports and decide if an investigation is warranted.

The purpose of an investigation is clear; to find out what’s going on, if it’s illegal and if so, who is responsible. But these questions often take years to answer. Requesting warrants, conducting interviews, calling for witnesses and producing toxicology reports are all routine procedures in criminal investigations. But investigating potential crimes against wildlife comes with its unique set of challenges, namely because wildlife is a ‘silent witness’. Greg says that, compared with humans, who “leave traces everywhere” – by talking with friends or family, maybe being seen on CCTV – animals simply do not produce that weight of evidence.

“It’s like a murder trial. We have to prove that there is guilt beyond all reasonable doubt,” Greg says. “Knowing [someone is guilty] is different from proving it.”

This is why investigations and court cases can take so many years. Proving that an individual human harmed an individual animal (let alone hundreds) requires a very strong basis of evidence.

“It’s not like CSI. It takes a lot of time,” Greg says, when explaining the amount of labour required to develop a water-tight case. “[There are] no quick wins.”

It took Greg and his team years to build a case against Sloan. They pieced together evidence by obtaining warrants to search her property, organising toxicology tests, keeping thorough records and partnering with other agencies.

A community witness provided valuable evidence in Sloan’s trial. Their testimony linked her to the eagles that were poisoned and shot, and led to the magistrate concluding Sloan had intentionally harmed the animals.

It can be hard to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that an individual committed a crime against an animal or plant. In these cases, local witnesses can make a difference by being the voice the environment needs. “The community is a key partner in ensuring those who commit environmental crimes are held accountable,” Greg says.

How common are these sorts of eagle killings? Greg believes these actions are the products of “a bygone practice”, and that crimes of this scale are, fortunately, now rare. He’s hopeful that prosecutions will deter people from committing such crimes in the future.

Community witnesses carry weight while investigating environmental offences. And the court documents and facts of these recent cases show that those who care about the environment can play a significant role in assisting the justice system – both through reporting incidents and providing testimony.

On 23 July 2024, Sloan was found guilty on 73 charges relating to wildlife crimes. The 84-year-old died before her sentencing, which was scheduled for last September.