There’s a quote by fictional character Doc Tydon in the 1971 outback thriller Wake in Fright that says much about life in remote Australia: “Discontent is the luxury of the well-to-do. If you live here, you might as well like it.” The film, which is as much an ode to the Australian outback as it is a tale of small-town parochialism and the urban-rural divide, focuses on ingrained cultures of heavy drinking, gambling and masculinity that are synonymous with depictions of life in the outback. It premiered in 1971 at the 24th Cannes Film Festival, where it was nominated for the Palme d’Or – one of the festival’s highest accolades. Now revered as a great piece of Australian cinematic history, it was initially criticised by domestic audiences for its unflattering depictions of outback life. It was also one of the earliest and most influential films to bring Broken Hill, in far western New South Wales, to the silver screen – the first being Uncivilised in 1936. Wake in Fright’s portrayal of inland Australia’s searing heat, swarming flies and dusty, scrub-studded plains, presented a visual exemplar that countless films have since emulated.

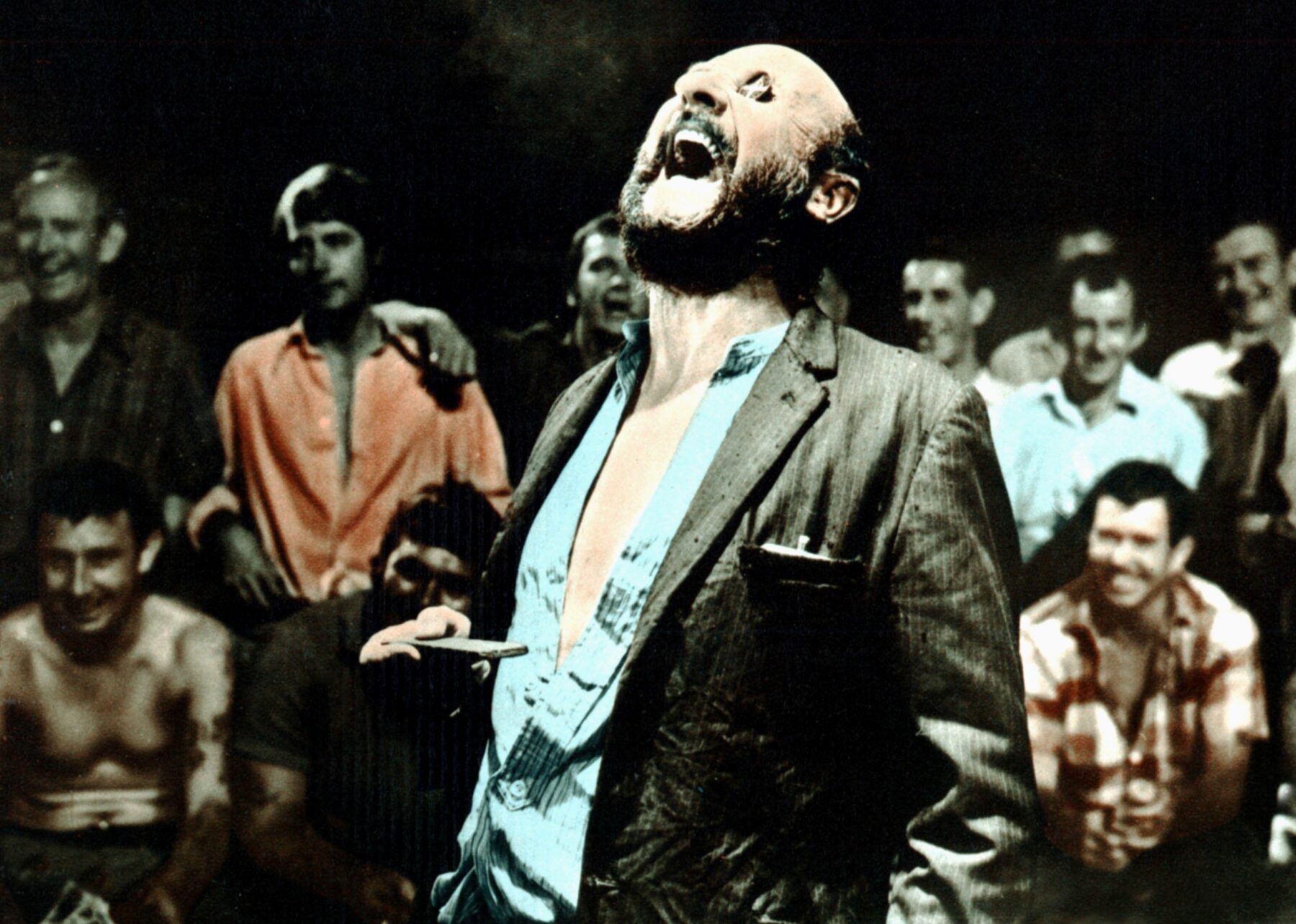

Based on the 1961 Kenneth Cook novel of the same name, Wake in Fright follows protagonist John Grant, a young schoolteacher from England, who’s fulfilling his bond to the education department by spending a two-year stint working in a one-room school in the fictional village of Tiboonda in the Horse Lake area. John, who dreams of escaping his dreaded post, is looking forward to spending the Christmas holidays in Sydney. However, on the way he finds himself stranded in the town of Bundanyabba – ‘the Yabba’. Here, he hopes to earn enough money to pay off his bond playing two-up but instead loses everything. In the sweltering heat of the dusty outback town, John finds himself at the mercy of the menacing locals, including Doc Tydon, who lead him on a journey of heavy drinking and debauchery, and on a particularly brutal kangaroo hunt. He spirals into despair, survives a suicide attempt, and eventually ends up back in the Tiboonda schoolhouse.

On location

The film was an international co-production between Australia, Britain and the United States, and was shot in and around the mining town of Broken Hill, one of Australia’s most isolated inland towns. Locations such as the Sulphide Street Railway Station, the Imperial Hotel, the RSL Club on Argent

Street and the Broken Hill Hospital all feature in the movie. Scenes of the outback, which is the unofficial star of the whole production, were shot at locations within proximity of the town, including Silverton, Horse Lake and Menindee Lakes.

The interior scenes were mostly shot in Sydney, including at the Palace Hotel on George Street in Haymarket. Scenes of the Yabba’s two-up school were shot on a set constructed in an abandoned warehouse in Paddington, with regulars from Surry Hills’ illegal gambling hub, Thommo’s Two-Up School, called in to play some of the gamblers.

The movie was directed by British-based Canadian director Ted Kotcheff, who was born in Cabbagetown, in central Toronto, to Bulgarian immigrants. Ted once said that feeling like an outsider in his country of birth helped him breathe life into the film, his life experiences helping to shape how protagonist John Grant, an English outsider, was portrayed. According to Ted, being an outsider in Australia also helped him see character traits that locals displayed but took for granted. Many Australian viewers did not see this angle, telling the director, “You come here to rubbish us”. British actor Gary Bond, best known for his role in the 1964 film Zulu, played disgruntled teacher Grant. Needing a star to help sell the movie internationally, producers hired British character actor Donald Pleasence to play Doc Tydon, who marvelled many on set with his bang-on Aussie accent. The rest of the key cast positions were filled with established local names, including Australian film icon Chips Rafferty who was, in fact, born in Broken Hill. Rafferty played local law enforcer Jock Crawford. Making a strong screen debut in one of the supporting roles was up-and-comer Jack Thompson, who went on to become a major figure in Australian cinema.

Shooting commenced in January 1970 and wrapped up by April. When Ted Kotcheff arrived at Sydney Airport for his flight back to London, he was given a send-off by Jack and the film crew. When Ted was asked whether he wanted any souvenirs to take back to England, he answered, “Yeah, can I have the whole crew please?” It was a testament to the skill of the Australian film technicians working in a very untried industry.

Post-production took place in both Australia and the UK. Australian film editor Anthony Buckley cut the film together in Sydney, with sound editors Keith Palmer and Tim Wellburn recording true-blue truck and outback sounds, including the revving noises of Fords. Upon the film’s completion, Ted screened the Australian cut to top British film editor Thom Noble. Impressed by the Australian team’s craftmanship, Noble said: “I wouldn’t touch a frame of it.”

Wake In Fright made its debut alongside another outback film, Walkabout, at the 1971 Cannes Film Festival. Both received high critical praise. French newspapers in particular singled out Wake in Fright for its honest portrayal of brutality and the art of making ugliness beautiful. Upon its screen premiere, the film certainly had an impact on one viewer, American filmmaker Martin Scorsese, who later left his own mark on the film industry with his use of artistic screen violence. The film went on to play for 10 months in Paris, based on its success there. Tragically, Chips Rafferty died of a heart attack the same month the movie premiered and didn’t get to witness what many thought was one of his best roles.

Despite critical acclaim abroad, the film’s reception at home was not so rosy. It was released in Australian cinemas in October 1971. With cinematography by Brian West and a haunting film score by John Scott, it offered a portrayal of outback life that audiences had never seen before. It presented an unpolished, uncomfortable portrait that left many viewers mortified. “That’s not us!” some shouted back at the screen. Wake in Fright was gone from cinemas almost immediately after it debuted and when it later aired on television, it received an abundance of hate mail.

Showing the way

Although nobody knew it then, Wake in Fright would become a cornerstone of Australian cinema, influencing generations of local filmmakers. Acclaimed directors Fred Schepisi and Peter Weir credited Wake in Fright for “showing the way”, giving filmmakers inspiration to tell interesting and dynamic Australian stories. Journalist, broadcaster and film producer Phillip Adams once said, “If it hadn’t been for these invaders telling us something about what we looked like and what our landscapes looked like, our cultural anonymity would have been utter”. The die was cast. The Australian film industry, which was in its infancy when Wake in Fright was released, was to go full throttle.

Ted Kotcheff continued using cinematographer Brian West in his follow-up projects. He received critical success once again with the 1974 comedy drama The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, which put an international spotlight on the Canadian film industry. In 1982, the director returned once again to the theme of the outsider in a small town with survival thriller First Blood, the first film in the Rambo franchise. To this day, after directing 19 feature films, Ted still rates Wake in Fright as his favourite from his extensive body of work, and the Australian crew he used for the 1971 thriller as the best he ever worked with.

Digital restoration

For many years after its release, Wake in Fright was out of circulation. By the late 90s, the film’s master negatives were believed to be lost and although some prints of the film still existed, they were in poor condition. Between 2002 and 2004, the film’s editor, Anthony Buckley, found the original film materials at a CBS storage facility in Pittsburgh in the USA, in a box marked, “for destruction”.

The lost classic received a full digital restoration and in 2009, it was screened at the 62nd Cannes Film Festival in the Cannes Classics section. Championed by none other than Scorsese, it received great praise once again. The lost gem finally found captive audiences when it hit Australian theatres, garnishing legions of fans, including musician and writer Nick Cave. Many hailed it as a darling of national cinema and as one of the greatest Australian films ever made. With themes that are still relevant today, Wake in Fright was remade as a two-part miniseries that aired on Australian television in 2017.

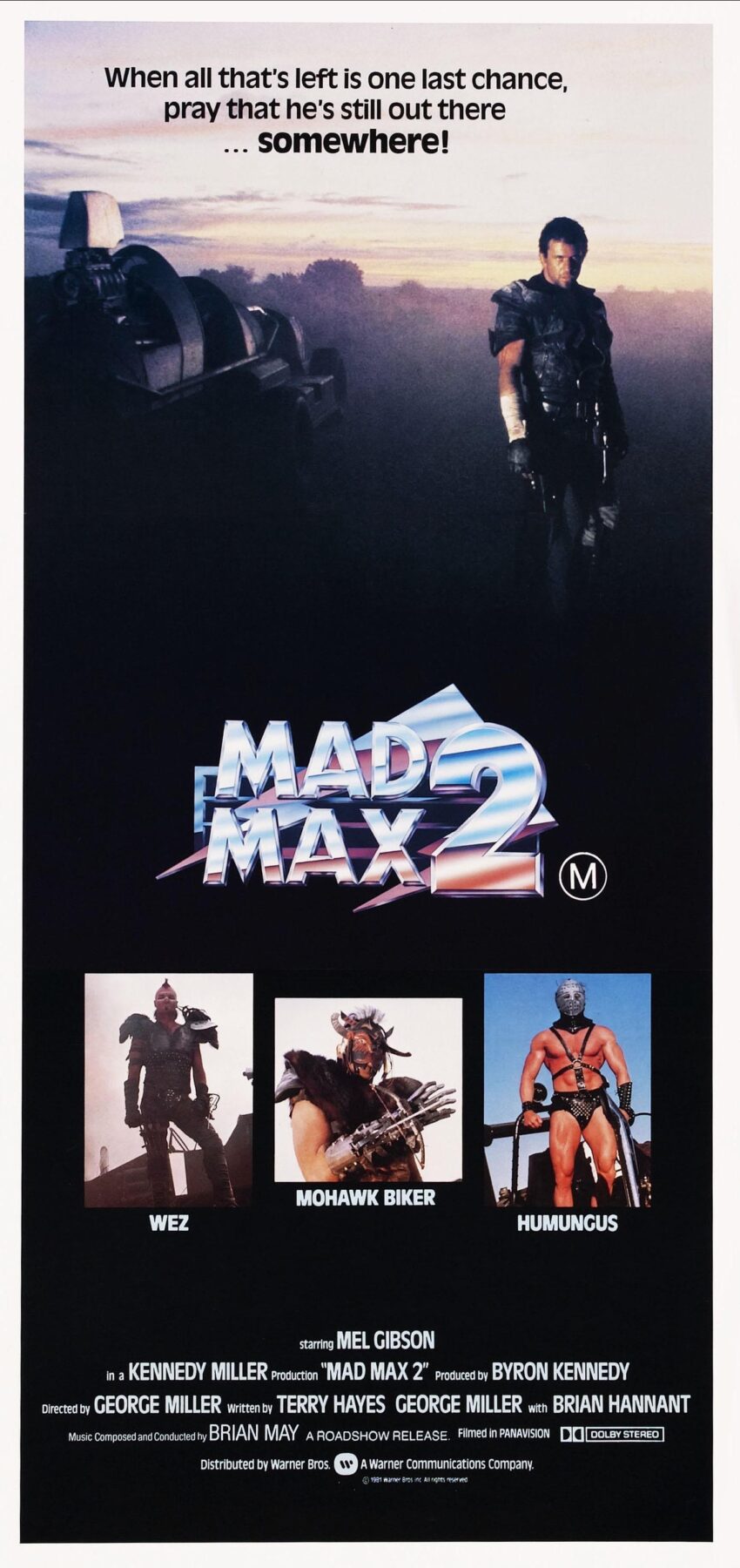

Broken Hill, the unofficial star of Wake in Fright, reaped the benefits of being in this cinematic gem. Today, the town is no stranger to the big screen, with many iconic films having been shot there, including Mad Max 2 (1981), Razorback (1984), and The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994).

The 2017 Wake in Fright miniseries was also filmed in the town, almost half a century after its predecessor.

Many of the key landmarks that featured in the original movie are still easy to find, with some seemingly unchanged since 1971. The Sulphide Street Railway Station, where scenes depicting the Bundanyabba train stop were filmed, is now a museum. The shack where shots of Doc Tydon’s home were filmed – off a small road on Piper Street East – has since been torn down but metal remnants of the former structure still remain on the vacant lot.

Scenes of the schoolhouse and the hotel at the fictional Tiboonda were filmed at Horse Lake, south of Broken Hill. The structures where these scenes were shot have also since been destroyed. In Sydney, in the historic Palace Hotel on George Street, you can still see where John Grant downed his beers under Jack Crawford’s disapproving eye.

Mentioning the film to Broken Hill locals can still garner a wary reaction, a tribute to the shock value it still has. Despite this, Wake in Fright gets an honourable mention in the local Visitor Information Centre and at the airport, which is one of the main production locations for RFDS: Royal Flying Doctor Service, a television drama series that began airing in 2021.

The legacy of Wake in Fright for the town has been profound. Ted Kotcheff’s love for this picture, and the hard work of the local film crew, placed them and the city firmly on the map of Australian film culture.