Unlocked: the genome of the mysterious marsupial mole

Native to Australia’s north-western deserts, marsupial moles are known as wonders of evolution. Cloaked in lush golden fur, their tiny pink vestigial eyes are covered by skin, and their powerful claws allow them to ‘swim’ – rather than tunnel – through desert sand.

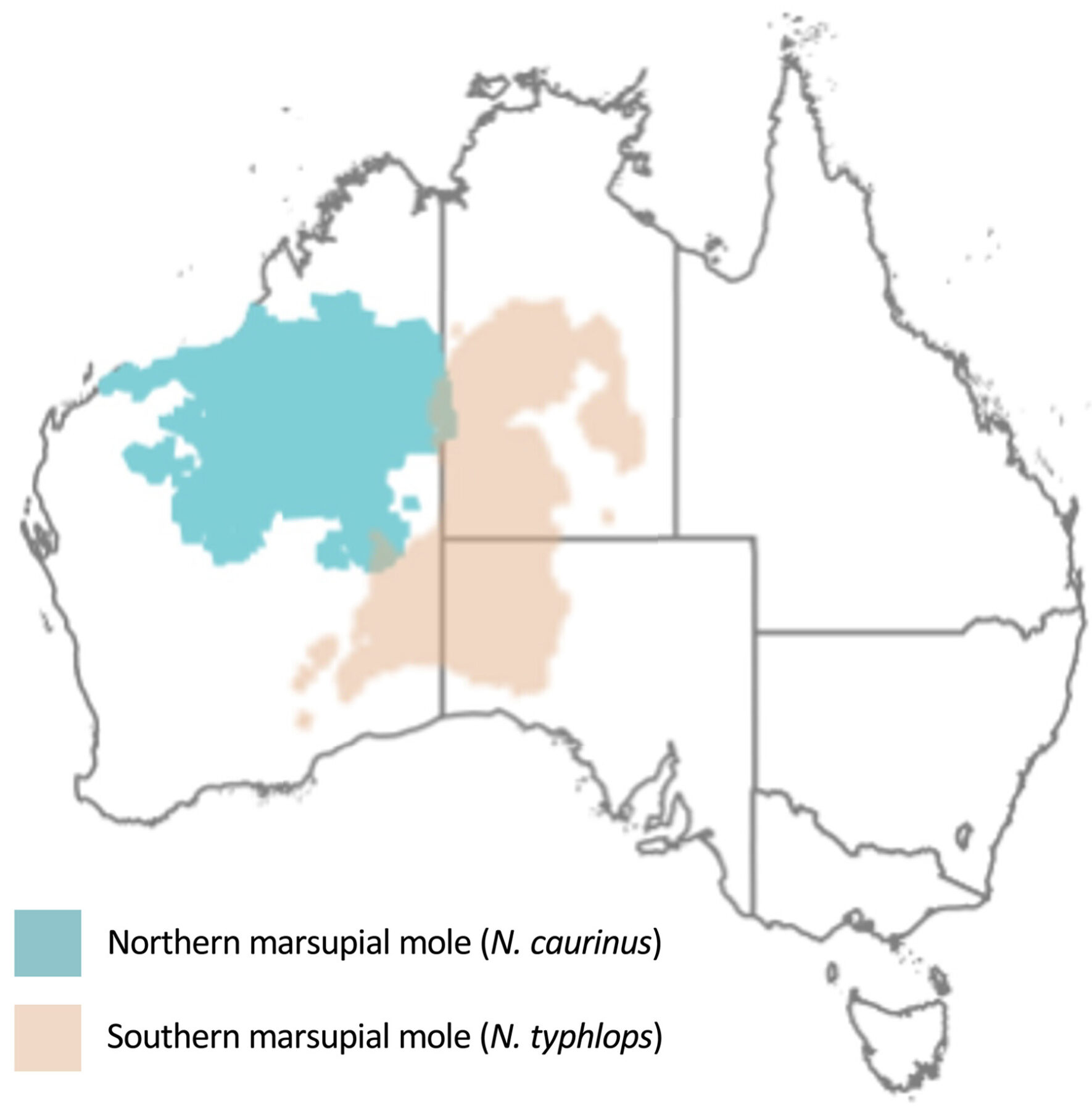

There are two living species. Known as ‘itjaritjari’ to the Anangu people of the Red Centre, the southern marsupial mole (Notoryctes typhlops) occurs in central Australia. The northern marsupial mole (Notoryctes caurinus) is found in north-western Australia.

These burrowing marvels are so rarely seen they are difficult to study, and it’s not known how many survive in the wild.

The genome was unlocked by an international team of researchers from The University of Melbourne analysing frozen cells from a South Australian Museum specimen of the southern species.

The results of their research were published in Science Advances, offering a window into the evolutionary history of this little-known marsupial.

It’s a breakthrough that brings science closer to understanding one of Australia’s most captivating creatures.

Burrowing into their genome

Analysis of the genome has revealed that marsupial moles have an extra gene for haemoglobin – the protein in red blood cells that transports oxygen around the body.

This may boost survival rates of pouch young in low-oxygen underground environments. It also indicated that bandicoots and bilbies are the closest living relatives of marsupial moles.

Tunnel vision

The study found that marsupial moles’ degenerating eyesight occurred in three stages, beginning with loss of the eye lens – important for creating a clear image – about 16 million years ago (mya).

This was followed by a loss of genes for cone receptors (9 mya), important for colour vision, and then rod photoreceptors (3 mya), which help with low-light or night vision.

“When you’re underground, in a dark environment, [vision] becomes less important,” said study co-author Dr Stephen Frankenberg, from The University of Melbourne. “The genes for the lens versus the genes for the cone and rod cells started to accumulate mutations at different stages during the moles’ evolution, which you’d expect would be the order of loss of different functional parts of the eye.

“The rod cells are the ones that are most important for [creating] an image in very dim light. And that was the functional part of the eye that was retained for the longest.”

Dr Frankenberg said the ancestors of marsupial moles were ground-dwelling animals that dug around in soil searching for food.

During the course of evolution, they began digging burrows – but not living in them – before they gradually swapped their above-ground home for a subterranean one.

Private investigation

Non-functioning eyes and an ability to swim through sand aren’t all that’s unusual about this creature.

The male marsupial mole’s testes are located inside its body, making it the only Australian marsupial without a scrotum.

The study revealed that a key gene for testicular descent – RXFP2 – isn’t functioning properly in the mole genome, possibly explaining why its testes are in its abdomen.

Dr Frankenberg said this adaptation is common in mammals living in subterranean and aquatic environments. However, it raises interesting questions about why this trait isn’t more commonly observed in ground-dwelling animals.

“If it’s possible to have evolved to produce sperm without having external testes, why don’t all mammals just do it?” he said. “Having a scrotum and testes that are outside the body is important for temperature regulation [because] there’s an optimum temperature for sperm production. But clearly, it’s not a game changer…because marsupial moles can still breed.”

Population crash

Genomic analysis also revealed the marsupial mole population declined sharply about 70,000 years ago – before the first humans arrived in Australia.

This suggests marsupial moles were affected during the late Pleistocene by climate change, including the cooler temperatures and dropping sea levels of the last Ice Age.