As the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment began its year-long deployment to South Vietnam in 1965, young Norman John Rowe thought he had the world at his feet. Blessed with a strong tenor voice, ‘Normie’, as the 18-year-old from Melbourne was known, had quit his trainee telephone technician’s job with the Postmaster-General’s Department (PMG) and set out to conquer the entertainment world as a rock-and-roll musician. Stardom came quickly; he enjoyed his first number-one hit in April that year. Normie Rowe had arrived on the music scene, but the lottery of life would soon disrupt the trajectory of his promising career.

Military conscription in Australia had been abandoned in 1959 but was reintroduced in 1964 to support the war effort in Vietnam. Controversially, this call-up of 20-year-old men now included the possibility of overseas service in the army. These national servicemen, or ‘nashos’ as they were colloquially known, were chosen by random ballot as each year’s eligible cohort came of age. Of some 63,000 nashos called up between 1965 and 1972, nearly 16,000 served in Vietnam.

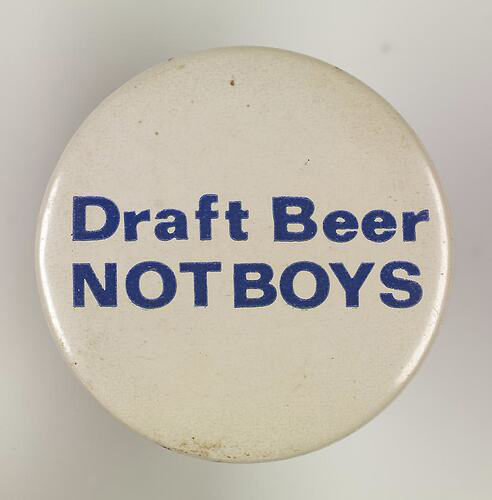

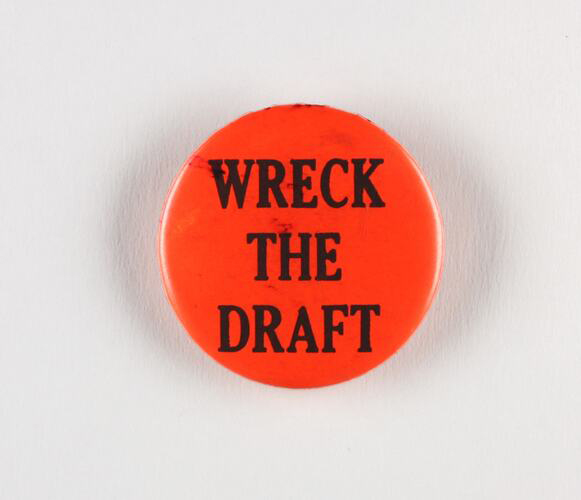

Both the war and conscription had widespread public support during the early days of Australia’s Vietnam War commitment. But this was a conflict like none before it. For the first time in history, each evening’s television news bulletin was headlined by graphic black-and-white footage illustrating the brutality of what was being perpetrated in our supposed national interest. And as casualty lists lengthened, public opinion soured. The issue of conscription was particularly fraught, and for many, the ballot came to be known as a ‘lottery of death’.

By 1966, with Normie’s career on the up, a crack at international stardom seemed the next logical step. He headed to England, but soon became aware of criticism being directed his way. “People [were] saying I was living [there] so I could get out of the draft,” he says. Normie was affronted by the suggestion, so he returned to Australia and registered for national service.

He was duly called up in late 1967, joined the 3rd Cavalry Regiment, Royal Australian Armoured Corps and served two years in the army. After four months in Vietnam, he was promoted to lance corporal and given command of an armoured personnel carrier (APC). It was a nerve-racking and stressful existence, living, sleeping and working in a mobile steel box in draining tropical heat, all the while in fear of mines and booby traps. In the lead on patrol, he had to be “really switched on to all the dangers” as the platoon’s engineers on foot probed gingerly for mines ahead of the vehicle. In Normie’s opinion, they were the bravest people he’d ever encountered.

“If I was to survive…I would have to be a good soldier,” Normie says. “The last thing I wanted was to be the cause of somebody else’s death.” Often lauded as a particularly Australian quality, the ethos of mateship remains precious to Normie. “You don’t fight for your country; you fight for each other,” he says. Mateship became a life raft on a troubled sea. But like many, Normie returned from Vietnam feeling aimless and alone.

Transition to normal life

From being on constant high alert to facing the ordinary preoccupations of civilian life, readjustment was a battle many Vietnam War veterans were ill-prepared to fight. Their world had changed irrevocably. Normie and all his close army friends, he says, felt different from the way they’d felt before they went overseas. To make matters worse, they “weren’t in the headspace to communicate all that” to those who hadn’t gone – not only those in the army who’d stayed behind but also their families, friends, and an Australian public that ranged from indifferent to openly hostile.

If you returned from Vietnam with a physical body more or less intact, senior command and the bureaucracy chose to do nothing. It was a response – or lack thereof – that now-retired Brigadier Adrian d’Hagé, who was a platoon commander in Vietnam and later the head of Defence Public Relations, describes as “nothing short of appalling”. Upon discharge, there was no help for nashos other than transport to their hometown or place of enlistment. The army gave them no counselling, no opportunities to debrief, and no help with the transition back to civilian life. “The army cast them aside, like redundant draughthorses,” Paul Ham wrote in his 2007 book Vietnam: The Australian War. They had fulfilled the onerous duties imposed on them by Australia, but it would be many years before Australia bothered enough to care adequately for them in return.

For a few weeks in early 1970, Normie whiled away time with one of his army mates, Tim Little. He and Tim were close. They’d trained together and had both chosen the cavalry for their deployment. Now they were rowing surfboats at the Torquay Surf Life Saving Club, near Geelong. With its own close-knit community, the club mimicked the army, and to some extent it offered a refuge – without the dangers of war. Soon though, Normie’s father was reminding him that his house was mortgaged and could be sold by the bank for less than he’d paid for it. Reality was hitting home.

With limited options, and his stardom now outshone by the likes of John Farnham, Normie decided to “go and do a show”. He sang at the Melbourne Velodrome, where “all the kids were calling out for the Zoot” – a popular band of the day that performed in pink outfits. Hardly a year before, Normie had been crowned the King of Pop by Go-Set magazine, but rather than adulation, all he now received was indifference. To the crowd, Normie represented what he called, the “anti, anti-war movement”. He was spurned because he “didn’t go to jail instead of going to war”, and as a consequence, he “literally died” on stage. Normie walked off dejectedly, resigned to finding another job. He even contemplated returning to the PMG.

From a unit of about 180 men, Normie had lost “about seven mates”. His year in Vietnam was the second-most deadly of the war for Australia, with 95 of our soldiers killed in battle. During his regiment’s entire deployment, “nearly 30” were killed or wounded, “most of them by mines”. Normie’s recent reality was a universe away from an audience of screaming young fans.

The deaths of two friends in particular – Keith Dewar and Bob Young, aged 21 and 22 respectively – Normie remembered most vividly. Both were nashos, like him. On 24 June 1969, after running over a “500-pound bomb” set as a mine, the pair’s 13-tonne APC was “thrown 20m in the air and fell back down on top of them”. Their bodies were crushed beyond recognition.

The casualties were mentioned in the troop’s next briefing. Normie’s response to the deaths was: “Shit, that’s bloody terrible!” A moment later, he asked, “What are we doing tomorrow?” The troop couldn’t look back, nor afford the luxury of introspection. Rather, they needed to always be “switched on to what was happening”. Dewar and Young could very easily have been any of them.

Two more friends – Bert Casey and Viv French – would die later in the year. In October, Bert’s APC was hit by rocket-propelled grenades (RPG). He was killed, and another trooper was mortally wounded. December would then prove particularly costly for the 3rd Cavalry Regiment. Among the dead that month was Viv. A regular soldier, he was only 19 when his APC hit a mine in the jungles of the May Tao Mountains, a stronghold of the Viet Cong enemy.

Moratorium protests

In 1970 the first of three moratorium protests saw about 110,000 people march against the Vietnam War in cities and towns across the country. The moratorium movement would become the largest protest campaign Australia had ever seen.

In the shadow of mounting public anger, Normie’s father said to him, “Look mate, you’re home now… Don’t make a big deal of it, don’t tell ’em where you’ve been…just try to forget about it.”

Perhaps that was well-meaning advice, but it was hard, so hard. “How could I forget Keith and Bob, or Bert Casey, Viv French, and all the other guys?” Normie exclaims. He couldn’t forget Vietnam – so he “just hid it” instead.

Such an impulse was common among veterans. The hurt they felt was profound. It was almost as if they were expected to keep a dirty secret. “It’s reinforced that you shouldn’t have gone in the first place,” says Gwen Cherne, the inaugural Veteran Family Advocate within the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA), and herself the daughter of an American serviceman who was in Vietnam. “You are ashamed, and that runs deep.”

After arriving home, most were reluctant to wear their uniforms in public. They were treated without compassion by a community either too lazy, or too preoccupied with its own concerns, to distinguish the government from the soldier who was compelled to do its bidding. Even the Returned Services League was known to shun Vietnam veterans. Some among the old guard who had served in the world wars described Vietnam as simply a police action and not a real war. For Adrian d’Hagé, such an attitude deserved “absolute condemnation”. “When I had bullets whizzing round my ears, they didn’t feel any bloody different to those of World War II,” he says.

The pain of rejection could also extend to family members. As recently as 2018, a veteran’s wife told Gwen Cherne: “I had to endure this. I couldn’t get a job… No one would speak to me, and I’m still being traumatised for being the wife of a Vietnam veteran.”

In 1973 Normie’s father died, aged 59 – an early death in part blamed on the stress of Normie’s absence in Vietnam. Life took more tragic turns, including the accidental death of his eight-year-old son, Adam, in 1979. Two failed marriages followed, and it all got too much. More than 30 years after returning from Vietnam, Normie Rowe was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Unable to cope with the anxiety brought on by the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” – to quote Hamlet – he was admitted to hospital in 2001. It was the day before 9/11. Numbed by his pain, all he could say when told of that horrendous event was, “Oh, shit. That’s a shame.”

“It had to do with this PTSD thing,” Normie admits with impressive candour. He had previously been in denial, insisting he couldn’t be suffering from PTSD as he thought he “never did anything dangerous” in the army. As if driving an APC didn’t constitute an ever-present danger, and as if one in seven soldiers from Normie’s regiment didn’t become battle casualties during the course of the war.

Three months in a psychiatric ward laid bare the true depth of Normie’s suffering. Just moving became a near-impossible battle; he spent the “first six weeks in the foetal position”. He minimised his trauma by saying: “There was only one time I was even in a firefight.” He might have continued to cling to such a dismissive narrative had his hospital carers not explained to him that “[every day in Vietnam] you knew that you could be killed… Every inch of that road could be mined, there could be boobytraps up a tree, there could be snipers… In the bunker up ahead, there could be someone there with an RPG.” As an APC commander, Normie felt an added burden. “It was a 24/7 job, and if you [made] one mistake – everybody dies,” he says.

According to Adrian d’Hagé, jungle fighting is “right up there in terms of stress”. The enemy, the Viet Cong, “knew the jungle like the backs of their hands” and were poised to spring an ambush or a surprise attack at any time. They appeared and disappeared as if by magic, silently fading into the jungle or merging with the villagers the Australians were there to defend.

Psychological trauma

Of the physical casualties from Vietnam, more than 3000 Australians were wounded in battle or injured in accidents. For a further 523, including 200 nashos, the war cost them their lives. For some, their physical health was permanently compromised, either from their wounds or from exposure to chemicals used by the Americans to strip the jungles bare and deny the enemy cover. For those unfortunate survivors, a cancerous cloud of Agent Orange and other noxious cocktails still lingers.

Many more suffered psychological trauma and moral injury. Normie is just one of the estimated 35,000 veterans alive today who carry, to varying degrees, a lifelong burden borne of their service in Vietnam. In 2021, nearly 70 per cent of veterans lived with at least one government-accepted disability, and almost 48 per cent suffered from mental health conditions. PTSD has unwelcome bedfellows including anxiety, depression, panic attacks, paranoia, alcohol and substance abuse, domestic violence, suicide, and a range of other social and psychological maladjustments.

For those men – and it was overwhelmingly men who were placed in harm’s way in Vietnam – the war didn’t end when Australia withdrew its last battalion in 1972. The war continues as a never-ending personal struggle, affecting their immediate families and even succeeding generations.

Known as ‘shell shock’ from the horrors of World War I and ‘battle fatigue’ in World War II, PTSD has existed for as long as humans have died fighting one another. Yet the condition’s stubborn persistence long after war’s end wasn’t fully appreciated until the 1980s, when PTSD officially became recognised as a psychological disorder.

But Gwen Cherne says the trope of the broken veteran is in many ways erroneous. “They are a tough bunch of individuals… They are still fighting for their community,” she says. “They established the only mental health service for Vietnam veterans and then expanded it to families. That exists today [as] Open Arms… [They] are taking responsibility for their own healing. It started as a peer-based support program and turned into a clinical mental health service, and now has peers back in to support veterans who are experiencing trauma.

“They are the ones still who are jumping up and down and holding the DVA to account. [Even as they age] they are still out there, advocating for younger veterans.”

On Normie’s road to confronting his PTSD, his old army mates – ones he described as “wonderful friends” – stood beside him. Tim Little was there, as was Brian Griffin, another from ‘3 Cav’. Both gave “stoic support” to Normie. “They helped [make] my journey bearable, [as] I might’ve helped make theirs,” he says. The bond of mateship forged in war remained unbroken in civilian life.

From those years travelling the long and uneven road to recovery, one event in particular stands out in Normie’s memory. In 1987 he was asked to do a public concert with an army band at the Lavarack Barracks in Townsville, Queensland. After the show he bumped into his “old mate” Jim Canuto, a First Nations regular soldier from Yarrabah in Far North Queensland. Jim had stayed in the army. He had risen to be regimental sergeant major and was therefore able, on the spot, to offer Normie the chance to take control of an APC once more.

The offer was too tempting to refuse. After many years out of the driver’s seat, Normie was delighted to find that his off-road skills hadn’t deserted him. But before Normie left the barracks, Jim said, “I’ve got one other thing I want to show you.” He took Normie to the edge of the parade ground and gestured to a large granite rock. “On the rock was a plaque with the names of all the 3 Cav guys who lost their lives, [listed] in chronological order,” Normie recalls.

The names before and after his deployment were mostly unfamiliar, but reading down to 1969 they almost appeared “to be larger in relief”; to protrude more visibly from the surface of the memorial plaque. As he saw those names he knew – especially Bob Young and Keith Dewar, and the date of their deaths – Normie began to shake. Jim put his arm over his friend’s shoulder and asked quietly, “Are you okay, mate?” Choking back tears, Normie said, “Jim, you know… from the day I heard that Bob and Keith had died, all of a sudden, this is the first moment I’ve felt like I’m a good person.”

Jim was perplexed. “What do you mean?” Normie tried to explain, recounting his perfunctory response to the news his troop had received that June day, 17 years before. Through all the intervening years, Normie hadn’t forgiven himself for what he considered to be a lack of respect for his fallen comrades. Even now, 50 years on from the end of the war, his voice quivers and the tears well up as he remembers those two mates. “That was my coming home moment,” he says. “I finally came home after 17 years.”

There would be setbacks and tragedies in the following years, but this encounter with Jim Canuto marked a turning point for Normie – his first steps out from the shadow of the Vietnam War. Speaking metaphorically, but no less powerfully, he continues: “That’s when I absolutely galvanised my resolve to bring as many of my mates – that is, 50,000 Vietnam veterans – [and] bring…those mates home, get ’em home.”

Normie’s visit to Townsville coincided with preparations for a National Reunion and Welcome Home Parade, which was to be held in Sydney on the first weekend in October 1987. The event was organised not by the government or senior command, but veterans – particularly those in the lower ranks. The organising committee on which Normie served was headed by his nasho friend Peter Poulton, whom Normie describes as a “baggy-arse” (private soldier) mate from 1969.

After Vietnam, Peter worked as a sergeant with the New South Wales Police Force in Goulburn. In 1970, he was the first responder to the suicide of a veteran wearing a full army uniform and medals. He was resolute in doing all he could to help his fellow veterans and stop such tragedies from occurring again.

Finally, a welcome home

The Welcome Home Parade had been a long time coming. Adrian d’Hagé says the attitude of the public had previously been a “black mark on the history of this country” – but here, finally, was a chance for the nation to come together and properly acknowledge the sacrifice of those who had served in Vietnam.

The Royal Australian Air Force organised what Normie described as a “milk run”, flying veterans from the remotest parts of the country, while commercial airlines ferried thousands to Sydney from more accessible towns and cities. And by car and bus and train they came, until some 25,000 men and women marched through the city streets on Saturday 3 October. More than 500 Australian flags – each representing a serviceman who had died – were carried at the head of the parade, watched on by a cheering crowd of about 100,000 people.

The following day, thousands of veterans and their families descended on The Domain in Sydney. At the same site where, 17 years before, protesters had rallied to the chant of “Hell no, we won’t go!”, the crowd bellowed its appreciation for the folk-rock band Redgum’s 1983 hit ‘I Was Only 19’. Lead singer John Schumann’s haunting lyrics and hard-edged voice combined in tribute to his veteran brother-in-law; a powerful image of a soldier fighting bravely in the jungles of Vietnam, only for the personal war to continue long after his return home. Released at a time when Australians were still squeamish about discussing the war, the song jolted the national psyche. By 1987 it was an anthem of commemoration and respect for those who had died or were blighted by the conflict.

While in the army, Normie was committed to his regiment and therefore rarely performed, but he sang his heart out on Sunday 4 October 1987. That day, along with Normie and Redgum, The Domain pulsed to the sounds of Col Joye and the Joy Boys, Lorrae Desmond, Dinah Lee, Don Lane and Little Pattie – performers who, as volunteers two decades before, had all entertained the Australian troops in Vietnam. The Domain concert instantly took the veterans back to the shows they’d so loved. Yet as one man remarked to The Canberra Times: “This was better… In Vietnam we had to go back into the jungle after the shows. Tonight, I can go home to my wife and kids.”

Veterans return

The diminutive Little Pattie (Patricia Amphlett) was just 17 years old when she toured Malaysia and Vietnam with Col Joye and the Joy Boys in 1966. She’d been a regular singer at Sydney surf club dances, and her first single recording ‘He’s My Blonde-Headed, Stompie Wompie, Real Gone Surfer Boy’ was a hit in 1964.

Ahead of the tour, a determined government official was repeatedly rebuffed by her anti-war father. “No child of mine will go to that place. That war has nothing to do with us,” Pattie recalls him saying. But following assurances that she would be safe, her parents relented and gave their permission. Perhaps indicative of a certain 1960s naivety, Pattie’s mother concluded: “I reckon we can trust that man. He’s from the government.” That trust would soon be sorely tested.

For Pattie, her first overseas trip was a grand adventure – the “biggest event” in her short life to date. (“It pretty well still is,” she admits.) More than 50 years on, the surviving audience members from the Vietnam shows are now grappling with old age, but in 1966 their faces were so young. “They looked like my brother,” Pattie says. “They were just like the kids in our street.” The tour had a profound effect on her and laid the foundations for a lifelong affinity with veterans.

Staging up to three concerts a day, the entertainers performed wherever the Australians were located. Nui Dat in Phuoc Tuy Province was the centre of operations for the 1st Australian Task Force (1ATF). At any time, Nui Dat might be home to upwards of 2500 personnel, and it was there on the afternoon of 18 August that Pattie, Col and the Joy Boys performed.

During the second show, the performers became aware of “bang bangs and explosions nearby”. The show stopped abruptly, and Pattie was whisked away in an Iroquois helicopter. The drama is still vivid in her memory; the normally jovial atmosphere among the troops was sombre and subdued. “We were flying over the battle,” she says. Out the open side door, the only thing she could see through the gloom of a late-afternoon tropical downpour was “all these red lights”. They were tracer bullets.

The battle Pattie witnessed from the air was unfolding at a rubber plantation at Long Tan, just a few kilometres from Nui Dat. There, an isolated Australian infantry company was outnumbered 10 to one by the Viet Cong. After fighting heroically and at great cost, the enemy was repelled, but 17 men from the 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment died that day, while an 18th succumbed to his wounds a week later. The youngest was 19. Eleven were nashos, all aged just 21. The Battle of Long Tan would prove to be Australia’s most costly action of the war.

To bolster the morale of the 24 soldiers wounded at Long Tan, Col and Pattie, still shaken from the events of the previous day, visited a military hospital at nearby Vung Tau. As they moved through the ward singing, one soldier in particular – a First Nations man – caught Pattie’s attention. He was lying near the door, his broken limbs swathed in plaster. She remembered that her “eyes kept going back to him”, and instinctively, she went over and gently held his hand until it was time to leave.

In August 1996, some 30 years after the battle, Pattie accompanied a government-sponsored pilgrimage of veterans to Long Tan to pay homage and remember their fallen mates. The journey was cathartic, Pattie recalls, but also troubling. “Visiting graves and seeing names that they knew – can you imagine the torment?”

On the bus to the battlefield, one man quietly asked, “You don’t remember me, do you?” Pattie looked him in the eye and began to cry. “Dave Cook… Bed one as I walked in that side entrance. You had plaster all over you.” Up until his recent death, Dave and Pattie would meet up from time to time. “He was a very special man. He meant a lot to me, and I meant a lot to him.”

To the veterans, Pattie remains their adored “little princess” of 1966. She has accompanied them on several more pilgrimages to Vietnam, where they “were able to get rid of some ghosts”. Life was now very different for the survivors of Long Tan. “They had a good time and for the first time in their lives they were treated like heroes,” she says.

There are profound lessons in the experiences of a 17-year-old girl who so bravely opened her heart to suffering all those years ago. As Pattie movingly concludes: “My life changed because of them. They helped me become the person I am. You can be an activist pacifist at the same time as loving these men. Sometimes governments don’t get it.”

Special thanks to Norman J Rowe AM; Brigadier (ret’d) Adrian d’Hagé AM MC; Gwen Cherne; and Patricia Amphlett OAM for their generous help with this story.