Coral bleaching has struck Lord Howe Island

THE 145,000ha marine park contains the most southerly coral reef in the world, in one of the most isolated ecosystems on the planet.

Following early reports of bleaching in the area, researchers from three Australian universities and two government agencies have worked together throughout March to investigate and document the bleaching.

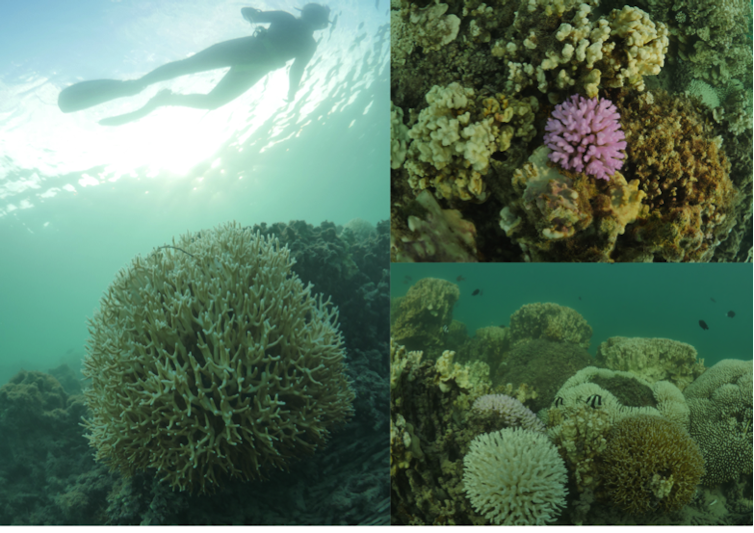

Sustained heat stress has seen 90 per cent of some reefs bleached, although other parts of the marine park have escaped largely unscathed.

Bleaching is uneven

Lord Howe Island was named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1982. It is the coral reef closest to a pole, and contains many species found nowhere else in the world.

Two of us (Tess Moriarty and Rosie Steinberg) have surveyed reefs across Lord Howe Island Marine Park to determine the extent of bleaching in the populations of hard coral, soft coral, and anemones. This research found severe bleaching on the inshore lagoon reefs, where up to 95 per cent of corals are showing signs of extensive bleaching.

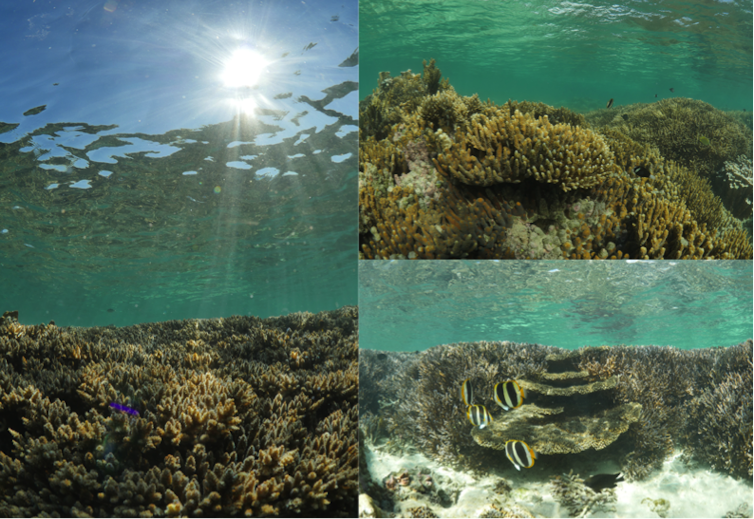

However, bleaching is highly variable across Lord Howe Island. Some areas within the Lord Howe Island lagoon coral reef are not showing signs of bleaching and have remained healthy and vibrant throughout the summer. There are also corals on the outer reef and at deeper reef sites that have remained healthy, with minimal or no bleaching.

One surveyed reef location in Lord Howe Island Marine Park is severely impacted, with more than 90 per cent of corals bleached; at the next most affected reef site roughly 50 per cent of corals are bleached, and the remaining sites are less than 30 per cent bleached. At least three sites have less than 5 per cent bleached corals.

Over the past week heat stress has continued in this area, and return visits to these sites revealed that the coral condition has worsened. There is evidence that some corals are now dying on the most severely affected reefs.

Forecasts for the coming week indicate that water temperatures are likely to cool below the bleaching threshold, which will hopefully provide timely relief for corals in this valuable reef ecosystem. In the coming days, weeks and months we will continue to monitor the affected reefs and determine the impact of this event to the reef system, and investigate coral recovery.

What’s causing the bleaching?

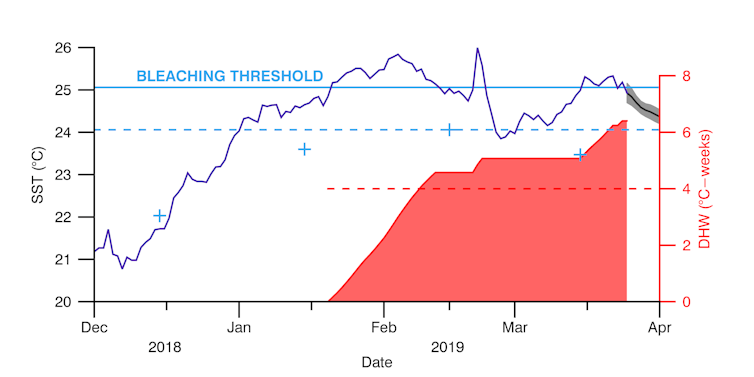

The bleaching was caused by high seawater temperature from a persistent summer marine heatwave off southeastern Australia. Temperature in January was a full degree Celsius warmer than usual, and from the end of January to mid-February temperatures remained above the local bleaching threshold.

Sustained heat stressed the Lord Howe Island reefs, and put them at risk. They had a temporary reprieve with cooler temperatures in late February, but by March another increase put the ocean temperature well above safe levels. This is now the third recorded bleaching event to have occurred on this remote reef system.

Satellite monitoring of sea-surface temperature (SST) revealed three periods in excess of the Bleaching Threshold during which heat stress accumulated (measured as Degree Heating Weeks, DHW). Since January 2019, SST (purple) exceeded expected monthly average values (blue +) by as much as 2°C. The grey line and envelope indicate the predicted range of SST in the near future. Source: NOAA Coral Reef Watch

However, this heatwave has not equally affected the whole reef system. In parts of the lagoon areas the water can be cooler, due to factors like ocean currents and fresh groundwater intrusion, protecting some areas from bleaching. Some coral varieties are also more heat-resistant, and a particular reef that has been exposed to high temperatures in the past may better cope with the current conditions. For a complex variety of reasons, the bleaching is unevenly affecting the whole marine park.

Coral bleaching is the greatest threat to the sustainability of coral reefs worldwide and is now clearly one of the greatest challenges we face in responding to the impact of global climate change. UNESCO World Heritage regions, such as the Lord Howe Island Group, require urgent action to address the cause and impact of a changing climate, coupled with continued management to ensure these systems remain intact for future generations.

The authors thank ProDive Lord Howe Island and Lord Howe Island Environmental Tours for assistance during fieldwork.![]()

Tess Moriarty, Phd candidate, University of Newcastle; Bill Leggat, Associate professor, University of Newcastle; C. Mark Eakin, Coordinator, Coral Reef Watch, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Rosie Steinberg, PhD Student, UNSW; Scott Heron, Senior Lecturer, James Cook University, and Tracy Ainsworth, Associate professor, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.