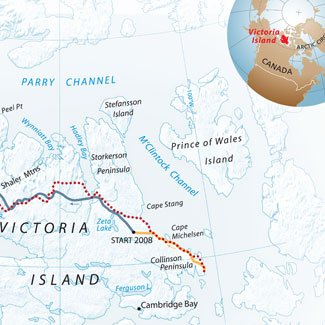

Crossing Victoria Island, Canada

Watch the documentary trailer

The Inuit have a saying: Ayuuknakmat, “It can’t be helped.” Right now, though, we had to at least try. “Come on! Paddle! Paddle!” Rearing above the tumbling water, dark rocks tear past our bobbing cart. Bleary eyes wide, Clark Carter and I bark futile advice at one another as the edge of a carbon-fibre wheel rim splinters against another submerged boulder.

“Have we got a puncture?” I shout, tearing my eyes from the situation unfolding ahead, flashing a glance at the four 1.5 m diameter wheels that are keeping us afloat as we’re swept broadside down the rapids. We’ve been alone in the Arctic for 43 days and we’re still 350 km from achieving our goal of walking 700 km across Victoria Island in Arctic Canada. Surely it isn’t about to end here.

The cart lurches violently. If a wheel fails, we’ll sink into the ice-strewn water, along with our 16 drybags of supplies. We dig furiously at the current, helpless against the flow of the Kuujjua River (translation: Big River). Finally, after bucking over river waves and troughs, we’re spat out the end and left spinning gently in a back eddy.

The historic crossing route

For several moments, we sit there, shaking, listening to the mournful cries of a pair of rough-legged hawks wheeling overhead. At least it isn’t the cold making us shake: it’s now midsummer, the 1 a.m. sun is shining down brightly and the temperature is a balmy 7°C.

Our expedition’s beginning, six weeks earlier, had not been so temperate. Snow flurries scurried across the frozen lake as we stood at our 2005 journey’s end-point (AG 82).

Piled around us collecting snow lay our dismantled Paddleable Amphibious Carts (PACs), along with everything we needed to survive 100 days in the Arctic, including 25 kg of chocolate and our new and improved camp-perimeter tripwire polar bear alarm. Fully laden, each PAC weighed 250 kg.

After recovering the Australian Geographic Society flag we’d buried in 2005, we loaded up, and turned on our GPS tracking system, which was linked to our website. “This is it!” I shouted. “Let’s go!”

We shouldered our harnesses and leaned forward. A wave of relief washed over us as our PACs started rolling – at last we were on our way.

Clark raised an approving eyebrow: “Not too hard, hey!” Two hundred metres later, as we tried to climb the snow bank out of the basin, excitement was replaced by reality. It was brutal.

“In theory,” I gasped, exhausted, into my video camera, sweat dripping from my face, “the PACs…can only get lighter and we can only get fitter…but…right now, I’m struggling not to just…fall to my knees and vomit.”

After just six days of hauling, something made me stop in my tracks. “Clark,” I said with a croak, “there are tears in our Kevlar wheel covers.”

This couldn’t be happening so early. Folds in the inner layer of Kevlar had created wear lines on the outside, and the sickening realisation sank in: we’d be lucky to have covers for a week. Unprotected, our balloon tyres wouldn’t last.

“I guess we just keep on hauling, until…”. Clark’s voice trailed off. “We’ll see how far we can get, anyway.”

Cold, hungry and eating painkillers for blistering feet and painfully strained Achilles tendons, we found the following days as much a mental struggle as they were physical. Step by step we pushed ourselves forward, bandaging the shredding covers with tourniquets of webbing.

The increasing summer warmth was a double-edged sword as the melting snow turned our world into one giant slushy. Each snowshoed step broke through the ice into water that froze our pants into a solid mass. In desperation Clark suggested linking the carts together and hauling in tandem, like a dog team. It made a big difference, and our moods lifted.

To our genuine surprise, on Day 19 we stumbled into Hadley Bay – we had made it, somehow, to the first milestone. To try to prolong the life of our wheels, we decided to head for the Kuujjua River, 75 km to the west, and attempt to raft down a 200 km section flowing in vaguely the right direction.

Unfortunately, another effect of the melting snow was our reacquaintance with two old foes: Victoria Island’s thick, sticky mud that sometimes forced us to unload and carry gear across it, one bag at a time, and good old “death terrain” – expanses of ice-shattered, razor-sharp limestone that slashed at the fraying Kevlar as we climbed the plateau of the western, hilly half of the island.

The lopsided rolling motion caused by our bulging tyres started to fatigue our PACs, and rolling down a slope on Day 30, one of the axles buckled. The repair took a full day in the rain as we cut off the bent part, shortened the other axle, chopped the PAC down the centre and riveted it back together so that it fitted the new axles – all with one brittle 5 cm fragment of hacksaw blade and a Leatherman multi-tool. Well, Ayuuknakmat. Making do with limited resources is half the fun.

Five days later, we somehow reached the river. As we triumphantly rolled the last metres into the water – the safe zone – we got our first puncture. Patching it with a bike repair kit, we had to laugh – Victoria Island wasn’t giving up her kilometres easily.

The first day of drifting lazily downriver – sun sparkling, relaxing to suitably grand classical music while enjoying the scenery moving past at 4 km/h – was Clark’s 24th birthday. We slid past Arctic wolves tearing into a musk-ox carcass on the banks and even managed to catch several enormous lake trout. We air-dried them the Inuit way and they lasted us for more than a week.

Buoyed, we decided to switch to non-stop river travel, living in our drysuits for days on end, which also helped protect us from the billowing clouds of mosquitoes. We ate, cooked and rested on our floating platform. It couldn’t last, and as the number of rapids increased, our time asleep decreased. By the time we reached our exit point on Day 45, we’d slept only three hours in as many days. We collapsed into the tent for a quick one-hour nap, and woke 18 hours later.

Each day, while Clark cooked dinner, I wrote updates for our website on our laptop, uploading them on our satellite phone. More than 13,000 people from around the world followed our progress, and we drew inspiration from their thousands of emails. We even had whole school groups following online.

The final leg of our journey was the biggest unknown – 200 km of tangled contour lines on our topographic map. Adopting blind faith and an excess of TLC for our Frankenstein wheels – now decorated with 18 tourniquets and large patches of unprotected rubber – we nursed the PACs towards the far side of the island.

Determined to stop us, Victoria Island threw up every conceivable obstacle, from hail, twister clouds and bucketing rain, to intimidating musk-ox bulls and fields of metre-deep moss, mazes of canyon-like valleys and jumbled boulder patches. By the time we crossed the 100 km-to-go mark on Day 62, our struggles had turned into a crusade – we would get there, even if we had to make a dash with nothing but backpacks.

Seventy days and 700 km after starting – 128 days and 1000 km if you include the 2005 component – we limped into the waves of the Arctic Ocean at the westernmost tip of Victoria Island and gave each other a hug. That moment was four years in the making, during which the journey had become our lives.

The things we’ve learnt and experienced between the two coastlines have set our personalities, taught us what to value, how to endure and enjoy, and engendered one hell of a friendship.

While trying to arrange a pick-up (the person we had originally organised was in jail), our bodies began to shut down. We’d pushed beyond our limits, and the instant we took the pressure off, our joints swelled and an overwhelming lethargy consumed us.

Worryingly, we had set up camp on a polar bear highway – and had a sticky moment when one, walking directly towards us, towered 4 m tall on his hind legs to get a good whiff before heading off. When the tug Jock McNiven steamed past five nights later and skipper Steve McKnight launched an inflatable dingy to ferry us and our gear out to her, we were ready to go home.

Stepping inside, warmth seeped into us and the smell of coffee hung in the air. “Welcome aboard!” Steve said. “There’s hot showers below and our cook will look after you.” She certainly did. “We’re going to get fat!” I said, laughing. “Oh well,” said a grinning Clark. “Ayuuknakmat – pass us another chocolate brownie.”

Source: Australian Geographic Jan – Mar 2009