Heart of darkness: exploring the far reaches of the Jenolan Caves

I’M HUNDREDS OF METRES down into the waterlogged cave system, hours from the entrance. After squeezing myself down a tight underwater tube I’ve become stuck.

The air from each exhalation is stirring up a haze of orange silt in the water, which makes it impossible to see. I try to comfort myself by running my hand gently along the thin string that is my only lifeline to the surface, careful not to risk it cutting on the sharp limestone rock.

The sound is deafening as the bubbles from my regulator come faster with the effort, and the twin steel air cylinders clang off the rocks above and below that I am trapped between. I try to push forward, but I bang my head, forcing me to take a gulp of the murky 14ºC water.

I’ve trained for this, and for far worse, which means I remain calm, but I am frustrated at wasting my air supply. I close my eyes, relax in the comforting grip of the rock, and systematically grope behind me until I find the hidden rocky protuberance my diving suit is snagged against.

The Speleological Society crew carries heavy equipment through the bush before reaching the cave entrance. Cave entrances at Jenolan range from claustrophobic tubes to cavernous openings. (Image: Alan Pryke)

THE JENOLAN CAVES are nestled high in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales, 175km west of Sydney. They have been a magnet for tourists ever since a cluster of large, interlinked caverns was found here by Europeans in 1838.

Aboriginal people had already used these caves for many thousands of years, apparently referring to them as binoomea, meaning ‘dark places’. They travelled great distances across the mountains to visit the blue pools nestled within what is now the tourist cave complex. Local lore told of how mineral-rich waters had restorative properties.

From the outside there is little indication of the vast mysteries lying beneath the earth. But here are hidden tunnels and chambers – ‘wild’ caves that have been explored by members of caving clubs such as our Sydney University Speleological Society for nearly 70 years.

The aptly named Mammoth Cave is one still revealing its secrets to those willing to work hard to find them. Our current map of it (see page 100) took more than a decade to create, with nearly 9km of surveyed passages, and much yet left to find. On this 2016–17 expedition, supported by the Australian Geographic Society, we are attempting to explore and map this cave under water, including a tunnel that we believe will be Australia’s deepest cave dive. Our team of two primary cave divers and two backup divers is supported by the skilled dry cavers of the Speleological Society. In 2016 more than 50 arduous exploration dives were made over monthly trips.

There is only one known entrance to this vast system, which – like the other entrances to caves here – is protected by a heavy locked gate. Only those with a NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service permit are able to access the caves.

After entering Mammoth Cave it takes several minutes for our eyes to adjust to the total blackness. The only illumination here is from the battery-powered lights worn on our helmets. From there we descend into the cave, carefully negotiating slippery and uneven surfaces and helping each other down tricky sudden drops, and around dark pits in the floor that are seemingly bottomless.

A gigantic vertical pile of boulders blocks the path in one section. Sometimes we use a rolled-up wire ladder dangled through a narrow hole to climb down a 12m drop to the level below. A quicker option is to descend directly through the guts of the rock pile, contorting and twisting around tight corners, ‘posting’ the body through very tight gaps called ‘squeezes’, and hopefully coming out the other side of the vertical maze.

After a short reprieve, the passage narrows to the point where we must lie flat on our stomachs and push forward with our toes. Many cavers don’t fit on their first go, and must breathe out fully to compress their bodies enough to fit between the solid rock pressing in from all sides. The physical challenge often creates fear, anxiety and claustrophobia, even in those who don’t usually suffer from it.

All of this is a noisy affair with the constant rustle of heavy-duty waterproof suits, squelching of mud under gumboots, and moans and groans from complaining bodies being bumped and contorted beyond comfortable limits.

At one point, if you look up, there appears to be a solid roof – but careful climbers can wriggle into a round opening and slide upwards through a tube. Eventually you reach an immense chamber sparkling with massive sheets of glittering white and orange crystal. Here we remove our dirty gloves, clothes, and shoes to preserve the white crystal floor. Upwards further, those brave enough to tackle difficult climbs can reach chambers even more magnificent. These are not yet fully explored and we still have questions about what may lie beyond them.

Dry cavers Dean (front) and Greg Ryan sometimes wait for hours for the divers to return. The group wears protective equipment, including safety helmets, waterproof gumboots, thermal undersuits and strong kneepads. (Image: Alan Pryke)

CAVING HAS TRADITIONALLY been a male domain, but Australia has produced several high-profile, female, dry-cave and cave-diving explorers who have become expedition leaders. Gender and job count for little once our helmet-clad groups are underground, with everyone treated equally regardless of the wide range of ages and professions.

Hypothermia is an ever-present risk and there are no navigational aids in these underground mazes, so local knowledge is essential to avoid becoming lost. Cavers must be entirely self-sufficient in these areas of no natural light, and ensure that they have the equipment required to stay underground for up to two days in an emergency.

“There are a lot of caves where it would be almost, if not absolutely, impossible to get you out of if you were badly injured,” says caving legend Alan Warild, captain of the NSW Cave Rescue Squad and an 2016 Australian Geographic Trailblazer. “Cave rescues in the past have taken two weeks or more.”

Jenolan is one of the most complex cave systems in the world, having undergone many distinct formation and destruction events across a brutal geological history. Scientists have determined these caves are at least 340 million years old, which means they predate dinosaurs by more than 100 million years. When the limestone was laid down 420 million years ago, the area was a coastal shelf teeming with prehistoric sea life, including coral and crinoids, today seen as fossils frozen into the limestone walls.

Cave divers such as Deborah (above) use the latest techniques to maximise depth, distance and safety. Experienced volunteer dry cavers such as David Reuda (above, behind) are integral to the success of these projects. (Image: Alan Pryke)

AFTER TRAVELLING FOR an exhausting hour into the system, we begin to hear a rumbling in the distance. Eventually our conversation is drowned out by the noise of an underground river violently bursting from a hole in the wall the size of a car tyre. The crystal clear water gushes along a rocky streambed and through a chasm before disappearing again through the floor. Speleologists have shown chemically that the underground water courses of these caves are interlinked, but most routes and destinations are mysteries that we are still slowly unravelling.

It is intense curiosity about that unseen world that motivates our cave divers to pack up to 80kg of scuba equipment into protective caving bags, which they push, drag and lower through the tunnels, relying on the help of others to reach each site.

Special care must be taken not to damage the equipment, because even small malfunctions could prove fatal. Although they are exceedingly beautiful, the delicate crystals of the caves become an obstacle that slows divers down, because we must take extra care not to damage them.

At the water’s edge, our divers struggle into ragged and torn diving suits and specialised scuba equipment modified to suit harsh cave environments. It is configured so that air tanks can be removed under water to pass through small holes called restrictions and redundancy is added by taking multiple tanks and lights.

Diving upstream here is only possible for strong and streamlined divers, because the water erupting from the pressure tube is constantly forcing the diver back out. With no point large enough to turn around, divers must back in feet first, finding protrusions on the rock to grip, pushing and pulling themselves deeper down the submerged passage.

With each body length, they reach ahead to pull closer the two cylinders of breathing gas being dragged along unattached. It is so tight in some places that one diver emerged with cuts on her face, while another had his mask smashed off when he tried to turn around to face the flow.

The furthest point of our upstream exploration is 55m below the water level, and about 150m below the surface above. We could see that the passage continued deeper still, but decided not to continue on when we reached an unstable sandy slope, which threatened to bury us alive.

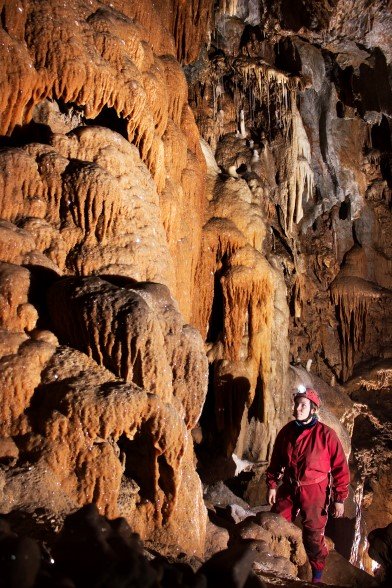

Deborah is dwarfed by Mammoth Cave’s crystal formations, deposited by mineral-rich rainwater that has seeped deep underground over hundreds of thousands of years. (Image: Alan Pryke)

THE FIRST AUSTRALIAN cave divers were hardy Sydney University cavers in the early 1950s, who ventured under water in the tourist system using homemade gear including garden hoses, waterproofed car headlights and hand-pumped bellows.

Success then was restricted by the lack of equipment and knowledge, but advances in technology and specialised training today allows divers to remain under water for many hours at depths previously thought to be impossible. We dive here to appreciate its beauty but also to answer questions about the cave geology, hydrology and biology.

There is another way to reach the waterway our divers have explored. The alternative entrance is an extra hour deeper into Mammoth Cave at the unfortunately named ‘Slug Lake’. From here, in 1998, Ron Allum, a diving legend and the AG Society’s 2016 Lifetime of Adventure winner, explored a passage to a staggering 96m below the surface before finishing in the roof of a chamber where it was too deep to see the bottom. His bright lights showed that the passage continued deeper out of sight, to what is possibly the deepest chamber in Australia. This is something we are continuing to explore.

Hydrogeologist Ian Lewis, based in Adelaide, did pioneering exploration dives at Jenolan in the 1970s. He explained to me why the caves here are so deep. “The Jenolan limestone layer has been tilted from horizontal, to near vertical, during the mountain building of the Great Dividing Range, with water filling old caves deeper down in the limestone,” he says. “The way the rock has been flipped means Slug Lake could potentially be several kilometres deep…this dive may intersect with an immense underwater aquifer, which is, of course, extremely exciting”.

Traditionally the goal of cave diving is to go furthest and deepest, but our team has spent much of 2016 exploring a new dry vertical cave found after diving down a tight tube to 30m and then surfacing in a subterranean lake further along the underground river known as Gargle Chamber.

In mid-2016 the divers broke into a previously unseen level of dry cave after reaching the top of a difficult climb 30m above the lake. This discovery revealed new dives even deeper into the cave system. It is hoped that further climbing will reveal a new pathway to the surface that will allow easier transportation of diving equipment. Once these new levels are fully mapped, the divers will return to the water, seeking the bottom of the so-called bottomless pit.

“It’s the only item on my bucket list,” says Sydney-based David Apperley, an award-winning expedition diver who has been integral in pushing the limits of our exploration of these caves. “I simply have to know where it goes.”

Returning to the surface after each exploration trip is difficult, because we must navigate a huge underwater void with limited visibility. Here, the only navigational marker is the thin orange string placed as a guideline to the surface at the entrance pool peppered with occasional plastic arrows that point the fastest way to air. There is a tight restriction to pass at the deepest point of this dive, where you have to wriggle through with difficulty. This is where I got stuck, but with a good grope in the dark for the rock snagging my suit, I was able to free myself.

There’s no space for ego on these exploration projects. The best results are gained through us working collaboratively. Success is rewarded in small doses and requires the repeated, methodical fortnightly or monthly trips, sometimes for years at a stretch. Cave-diving progress is often incremental with many setbacks before we begin to understand each cave system. Physical fitness and mental calm is essential to survive, but patience and passion is also necessary to last the distance.

Some say the desire to explore is innate but it is hard to articulate what continually draws us back. For some it is often a deeply personal feeling of satisfaction, for others, it is the combination of overcoming physical challenges and satisfying scientific curiosity. For those who have succumbed to ‘virgin cave fever’, it is the thrilling feeling of being the first to discover new caverns and seeing something no human has ever seen before – all here at the Jenolan Caves, just a couple of hours from Sydney’s CBD.