‘Deeper than Mt Everest is high’: Diving the Mariana Trench

ON 28 APRIL, after three years of intensive preparation, Victor Vescovo finally reached what’s now the deepest-known part of the planet: 10,928m under the ocean in the Pacific.

Nestled inside a purpose-built deep-submergence vehicle (DSV) called Limiting Factor, he dived to the bottom of the deepest ocean trench, reaching 16m further than anyone before.

The previous record for a solo dive was 10,908m, set by filmmaker and explorer James Cameron in the Deepsea Challenger in 2012.

Victor’s record-breaking dive took him deeper than Mt Everest is high, to a cold, lightless, high-pressure place as inaccessible as outer space.

It was the fourth successful leg of his Five Deeps Expedition, which was designed to send a human to the very bottom of each of the world’s five oceans: the Puerto Rico Trench in the Atlantic, South Sandwich Trench in the Southern Ocean, Java Trench in the Indian Ocean, Challenger Deep in the Pacific and Molloy Deep in the Arctic.

The latter was the last left to reach at the time of going to press. A five-part documentary series filmed by Atlantic Productions is due to be shown on the Discovery Channel at the end of this year.

More: Purchase your award tickets! This year’s guest is ocean explorer Victor Vescovo

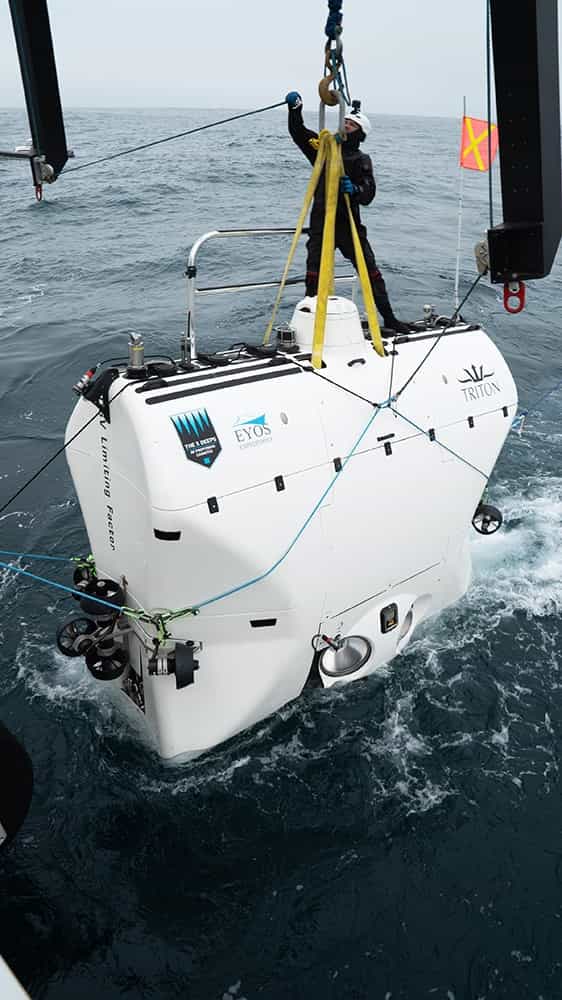

Launching the Limiting Factor submersible into the wild and frigid Southern ocean from the stern of DSSV Pressure Drop was like a finely choreographed ballet for humans and heavy machinery.

The decision to embark on the Five Deeps Expedition was made by Victor in 2015 while undertaking The Explorers Grand Slam – climbing the highest mountain on each of the seven continents and skiing to both the north and south poles.

After exploring Earth’s highest peaks it seemed natural he should seek its lowest depths. But he’d been mulling over the concept well before that and already knew there was a huge problem: he’d need a submersible craft capable of repeated dives to some of Earth’s most inhospitable places and such a thing didn’t yet exist.

And so Victor partnered with Triton Submarines, based in Florida, to design, build and test the next generation of deep ocean research and adventure vehicles.

The result was a submersible that resembled a white-bread sandwich. It was officially dubbed Triton 36,000/2 (for 36,000-foot capable, with two persons) or FOD Triton (Full Ocean Depth). Victor, however, christened it Limiting Factor after the name of a spaceship in a book authored by the late science fiction writer Iain M. Banks.

Limiting Factor is a revolutionary craft but to explain why, it’s necessary to recap some deep sea history and marine physics.

Earth’s deep ocean trenches have been, and are still being, formed as the planet’s tectonic plates crash into each other: one slipping beneath another during a process known as subduction. Trenches are the deep furrows formed at the boundaries between subducting and overriding plates.

The deepest is the Mariana Trench, near Guam in the North Pacific and its deepest part is known as the Challenger Deep, nearly a gobsmacking 11km below the surface.

The pressure at this depth, due to the massive weight of the overlying water, is 1100 times that at sea level: about 16,000psi (pounds per square inch) compared with 14.7psi at the surface.

It’s like the weight of a locomotive engine stacked onto your fingernail. Extraordinary engineering is therefore required to construct a vehicle that can reach the so-called hadal depths and return in one piece.

The first of the three piloted vehicles to visit the Challenger Deep was the bathyscaphe Trieste, in 1960, piloted by Swiss engineer Jacques Piccard and US Navy Lieutenant Don Walsh.

To the astonishment of the world, the ground-breaking expedition reached 10,911m down – the deepest any vessel, crewed or uncrewed had reached.

Trieste was a large steel sphere attached to a gasoline-filled ‘steel balloon’. Because gasoline is lighter than sea water, it provided sufficient lift to bring the bathyscaphe back to the surface.

Trieste was designed and built by Jacques and his father, Auguste, a fellow explorer, and was bought by the US Navy.

It took five hours to reach its destination and a further three to return to the surface.

Trieste didn’t carry any scientific research equipment or external cameras that could withstand the pressure.

When it touched down on the bottom it raised a silt cloud so dense it was impossible to see out. Trieste spent less than 30 minutes on the bottom, but proved it could be done.

The US Navy persisted with the Nekton program, featuring further Trieste dives, for another six months before winding it down.

For the next 50 years, deep ocean science was the domain of ‘landers’ – unpiloted robot vehicles that can collect biological and geological samples and record video.

The next piloted DSV capable of reaching such depths was the James Cameron-designed Deepsea Challenger, built by Australian engineer Ron Allum and his team (see Legend of the deep, AG 110).

Technologically, it was a quantum leap from Trieste.

The core of both vehicles was a steel sphere to protect the occupant from the crushing pressure, but that’s where the similarities ended.

Unlike Trieste, Deepsea Challenger could hold only a single pilot, in somewhat cramped conditions, but the technology was remarkable.

Allum had developed and patented a form of syntactic foam called Isofloat to provide buoyancy for the 12-tonne vehicle.

Isofloat contains millions of tiny air-filled glass spheres embedded in an epoxy resin – as strong as steel, yet it still floats.

Deepsea Challenger was orientated vertically to descend more easily through the water column. And it was decked out in lights and 3D cameras so James could record his historic dive in vivid detail.

The vessel was designed to make repeated dives, but, after completing just one mission to the Challenger Deep and suffering some damage, Cameron donated it to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, in Massachusetts in the USA.

In 2018 the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney hosted a collection of objects from the Deepsea Challenger project, which recognised Australia’s significant involvement in deep ocean research.

While the technological change from Trieste to Deepsea Challenger took 52 years, the next leap, to Limiting Factor, came in only six. Its pressure sphere is made from titanium, not steel, and it’s large enough to seat two people in relative comfort.

Designed and manufactured to be fully reusable, it’s the only submersible to gain Full Ocean Depth (FOD) commercial certification. This means it can safely carry passengers, scientists and crew to any part of any ocean.

It’s why Limiting Factor is perfectly suited to reaching the bottom of the world’s oceans like no vessel ever before.

A moderately sized mother ship, plus a launch-and-recovery system and support team are needed, but the science and adventure possibilities are endless. The unexplored territory in deep ocean trenches is estimated to be about the size of Australia.

THE First of the Five Deeps to be achieved was the Atlantic Ocean’s 8376m Puerto Rico Trench, which Victor reached on 20 December last year.

This was swiftly followed by the Southern Ocean’s 7434m South Sandwich Trench on 3 February 2019.

The third was the Indian Ocean’s 7192m Java Trench on 10 April this year.

Victor and Glenn.

The Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench was the fourth. And the final and fifth record was to be broken as we went to press, when

Limiting Factor was expected to head to the bottom of the Arctic Ocean’s 5670m Molloy Deep.

The Southern Ocean expedition was the most challenging in terms of remoteness and weather.

The South Sandwich Trench is about 850km south-east of South Georgia, which is itself 1390km from the Falkland Islands.

Most of the South Sandwich Trench has never been sonar-mapped, so the goal was to thoroughly map the trench before diving to its deepest points.

The expedition’s mother ship is a 68m ex-US Navy Stalwart class Cold War submarine hunter now called DSSV Pressure Drop.

Its quiet diesel electric motors permit communication between the surface and Limiting Factor by using high-tech underwater acoustic communications systems.

The wild card in any Southern Ocean expedition was always going to be the weather. Compounding already sub-zero air temperatures, the high-speed westerlies of the Screaming Sixties whip up monster swells and a vicious wind-chill.

Massive icebergs up to 20km across dotted the ocean, while humpback whales breached, chinstrap penguins screeched and albatross lazily swooped around the ship.

The crew complement included marine engineers, electronics and communication specialists, scientists, filmmakers, sonar operators, submarine life support engineers, an ice pilot and a doctor (myself).

Launching a submersible into the Southern Ocean is not for the faint-hearted. To be prepared, the team practised the launch-recovery system in the relative safety of Cumberland Inlet on South Georgia.

With practice, a complex manoeuvre involving the ship, the tenders, the cranes, the crew, the communications systems and the film crew was fine-tuned.

Mt Paget (2934m) and the other mountains of the Allardyce Range towered over the team as they worked in the calm waters of the inlet.

Like most visitors to South Georgia, the crew paid their respects at the grave of the great 20th-century polar explorer Ernest Shackleton near the ruins of the Grytviken whaling station.

The Southern Ocean is home to Earth’s highest waves, strongest currents and most powerful winds.

The expedition plan was to sonar-map the South Sandwich Trench while waiting for a weather window to dive.

As it happened, the weather window came sooner than expected. Almost as soon as the deepest point in the Southern Ocean was mapped, Victor decided to dive.

The launch sequence was repeated flawlessly in open ocean and at 1.15pm on 3 February, Limiting Factor was on its way down to the 7433m bottom.

The very cold water created some problems – a large thermocline at 4000m prevented acoustic communications – and the deck crew suffered in the bitter cold. But after a three-hour descent, Victor reached the bottom, becoming the first human to visit the deepest point of the Southern Ocean.

Dr Alan Jamieson holds amphipods retrieved from the science landers that supported Limiting Factor in the South Sandwich Trench. (Image credit: Glenn Singleman)

YOU MIGHT THINK there would only be emptiness and desolation here, but patience and careful observation revealed life-a-plenty to Victor, as has been the case in the other trenches too.

On video, amphipods – a type of crustacean – can be seen darting around Limiting Factor, and one of the landers filmed three new species of snailfish.

Worldwide more than 9950 species of amphipod have been described and Dr Alan Jamieson, Five Deeps Expedition chief scientist, is confident more were discovered in the South Sandwich Trench.

Alan is concerned about the human pollutants such as PCBs, micro plastics and lead that have been found in deep-sea fauna in other trenches. He and his colleagues are analysing the samples obtained from the South Sandwich Trench.

When Victor returned to the surface, he had to be careful not to come up under an iceberg. Fortunately, communications were re-established when the submersible was above 4000m and he was given the all clear to surface. Like the record-breaking Mariana Trench dive that would follow nearly three months later, the Southern Ocean dive was a spectacular success.