All that glitters: the fossils of Lightning Ridge

John Pickrell

John Pickrell

I’D NEVER BEEN on an outback dig before, so travelling to the mining town of Lightning Ridge to spend a week working with Australian Opal Centre (AOC) scientists was an exciting proposition.

I’d first contacted palaeontologists Jenni Brammall and Dr Elizabeth Smith about opalised fossils in 2008, and I’d seen pictures of the eye-popping specimens in their collections, so I was looking forward to meeting them in person.

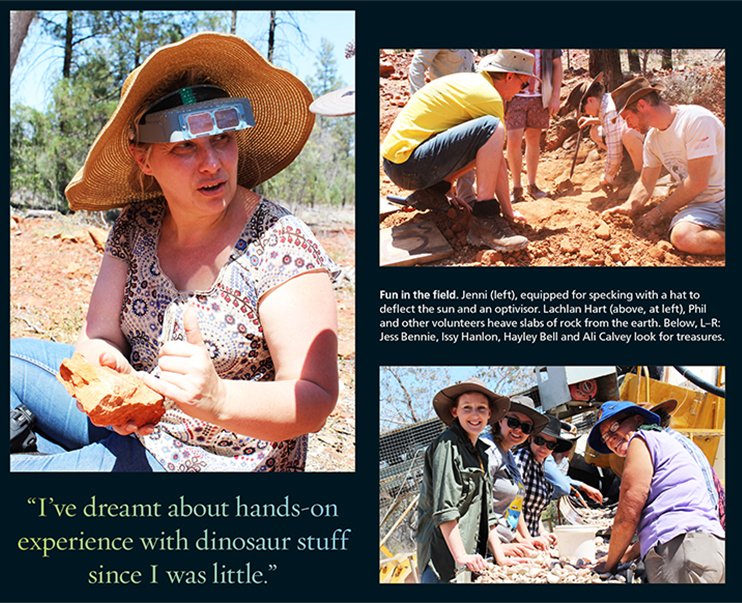

I arrived on a hot October afternoon in 2014 for a week of searching for, sorting and identifying fossils, alongside Jenni, Elizabeth, Dr Phil Bell – a palaeontologist at the University of New England (UNE) in Armidale – and an eager group of volunteers from all walks of life.

It sounds like something from fiction, but found across Australia’s opal fields are the fossils of dinosaurs and other creatures preserved as precious opal – some are incredibly beautiful, gem-quality specimens worth tens of thousands of dollars.

Opalised fossils are found around other opal field towns, such as White Cliffs in NSW and Coober Pedy in South Australia, but Lightning Ridge has the greatest number and diversity. It is one of the most productive and scientifically significant fossil sites in the country, and the only major site in NSW with dinosaurs.

Lightning Ridge is also a working mining town with a frontier atmosphere, unusual heritage and almost lunar landscapes, where people toil for decades in small-scale mining operations, hoping to make the big find that will set them up for life. The town sits on one of Australia’s major opal fields and produces black opal, the most valuable variety.

Massive opalised fossil collection

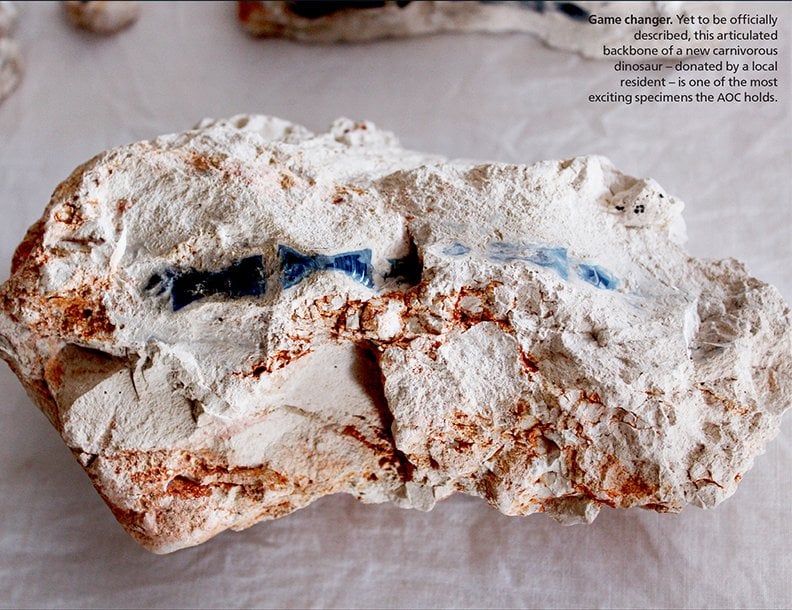

Three Australian dinosaur species have been described from Lightning Ridge material, but there are many more dinosaur specimens in the AOC collection that have not yet been studied or named. Other fossils include: turtles, crocodiles, fish, birds, early mammals, mussels, snails, giant marine reptiles, pine cones, plant stems and seeds.

The AOC has 4000 or more fossils in its collection, worth an estimated $3 million, but with Jenni and Elizabeth the only palaeontologists on site, much of it has yet to be studied.

Phil recently returned to Australia after a decade studying dinosaurs in Canada and gladly took up the opportunity to work with the AOC.

“Dinosaur palaeontology has limped along for the last 80–100 years in Australia, hindered by the fact their bones are very rare here,” he says. “When I returned in 2013, top of my list of places to visit was Lightning Ridge. I had no idea of the diversity or richness of the fossil material, but I knew it was unstudied. When the AOC opened up its vaults I was gobsmacked. I immediately saw I would be spending the rest of my career here.”

He hopes that in the near future we might double the number of known Australian dinosaur species based on fossils in the AOC’s collections. “This is the best preserved ancient ecosystem in Australia in terms of the diversity of species. It just requires people to study them,” he says. This is where the volunteers can help.

Unusual fossil dig

‘DIGGING’ FOR DINOSAURS here at Lightning Ridge is not exactly what you might expect. For a start, there’s not a great deal of digging involved. The opal miners have already done most of the heavy lifting, excavating the Cretaceous-era sediments and bringing them to the surface. On the old fields, this is left as mullock heaps, and it’s in these that we set about searching for fossils that miners have missed or ignored.

On a series of days we go out ‘specking’, which involves lying or kneeling on the ground, carefully turning over rocks looking for the flash of colour or unusual shape that suggests a fossil; we do this at various sites around ‘The Ridge’, each of which has subtly different deposits.

Similarly painstaking work involves picking through mine tailings; promising sediments brought up from the mines are run through agitators, which are modified cement mixers that wash away soft sediments leaving larger lumps to be searched for opals and fossils.

We sit at tables in the AOC’s shed and, over a number of days, learn how to spot fossils in the tailings and identify them. I find this meditative and oddly enthralling and it quickly becomes my favourite activity. We also get a series of interesting lectures about the opalised fossils, dinosaurs, and opal mining history. On other days we also team up to make moulds and casts of carnivorous dinosaur vertebrae and spend a couple of hours down a real opal mine.

The most exciting moments are when somebody finds an unusual fossil and everybody gathers around for a closer look. As there are 20 of us picking through the tailings, this is common, and some of the most exciting finds we make are sauropod teeth, dinosaur toe bones and vertebrae, fish jaws and pieces of turtle shell. The most beautiful fossils are tiny pine cones and spiral snail shells.

Dinosaur tragics

The volunteers I spend the week with are a diverse bunch – from students to seniors and botanists to accountants – and everyone I ask has found something different to love about the experience.

Lachlan Hart, 30, is a primary school teacher in Sydney and is about to embark on a PhD in palaeontology at UNE. “I’ve dreamt about hands-on experience with dinosaur stuff since I was little and it’s not something everyone gets to do,” he says. “We’ve also had a great insight into the lives of opal miners and what really drives them and how hard the work is.”

Ali Calvey, a retired nurse from Grafton, NSW, describes herself as a “dinosaur tragic” but says she never imagined she’d have an opportunity to dig for dinosaurs and opals.

“It’s difficult to get involved in finding opal out here because the sites that the public can speck on change from year to year, so if you’re only coming up for a few days it makes it difficult knowing where to go.” She says she was impressed with how the AOC worked hard to make the experience as safe and comfortable as possible for older members of the group, keeping people well fed and watered, and out of the sun during the hottest parts of the day.

Jan Haverfield, 54, an amateur gemmologist from Elsternwick, Victoria, came along because she was fascinated by opal. “One of my favourite TV programs is Time Team…but not being in the academic world, I didn’t know how you go about getting involved in that sort of thing,” she says. “[The dig] was a combination of something I’d really like to do, and opal, which is something I’m interested in. But I’d never have gone prospecting on my own.”

She says her highlights for the week were finding opalised turtle shell and going down into a mine. “I’d do this again at the drop of a hat,” she adds. “I was born and bred in the city, but I’m a country girl at heart.”

Self-taught palaeontologist

ELIZABETH SMITH, now a world authority on opalised fossils, first arrived at ‘The Ridge’ with her husband, Robert, in 1973. They came on a whim in a campervan but loved the atmosphere and decided to stay. While he searched 20m beneath their claim for ‘nobbies’ of black opal, Elizabeth – who then had no training as a palaeontologist and knew little about fossils – set about specking in mullock heaps.

She soon found small treasures, sometimes in gem-quality opal. “On hands and knees, nose to the opal dirt, I was enchanted. There were shreds of forests and fragments of long-extinct animals,” she says. “Fascinated, I began to collect fossils immediately – a raw amateur, overwhelmed with curiosity and furious with my own ignorance.”

At this time, next to nothing was known about the fossils of Lightning Ridge and few scientists had studied them. Elizabeth sometimes sent small parcels to palaeontologist Dr Ralph Molnar at the Queensland Museum, and he identified one find as a tooth of herbivorous dinosaur Muttaburrasaurus. Aside from Elizabeth and Bob, however, other miners had started to amass small collections of fossils.

Dave and Alan Galman’s fossil collection

By 1984 brothers Dave and Alan Galman had one of the largest. They decided to sell it, and approached Dr Alex Ritchie at the Australian Museum in Sydney. He came to see their collection in a motel room, where it was spread on every surface. One tiny translucent fossil in particular caught his attention. “The hair stood up on the back of his neck and his hands began to shake,” Elizabeth recounts. “He was holding the jaw of Australia’s oldest mammal.”

By 1984 brothers Dave and Alan Galman had one of the largest. They decided to sell it, and approached Dr Alex Ritchie at the Australian Museum in Sydney. He came to see their collection in a motel room, where it was spread on every surface. One tiny translucent fossil in particular caught his attention. “The hair stood up on the back of his neck and his hands began to shake,” Elizabeth recounts. “He was holding the jaw of Australia’s oldest mammal.”

Prior to this discovery no Australian mammal fossils older than 22 million years were known. This piece of primitive platypus relative, later named Steropodon galmani, would push that figure back to more than 100 million years ago, during the early Cretaceous. The find was so significant that in 1985 it made the cover of top scientific journal Nature.

In the 1990s Jenni Brammall – now AOC manager – was a postgraduate student in palaeontology under Professor Mike Archer at the University of New South Wales (UNSW).

“Someone was writing to the university with drawings and descriptions of fossils and asking for information,” she says. “It was Elizabeth.” Led by Henk Godthelp, the university sent teams of experts, including Jenni, for field trips. Elizabeth used her local knowledge and contacts to help get access to mining claims potentially harbouring fossils.

For many years the finds went to the Australian Museum and UNSW. But many important fossils were in private hands in Lightning Ridge and locals were understandably reluctant to send them 800km away to Sydney. From the late 1990s, a public collection began to be assembled by the Lightning Ridge Opal and Fossil Centre.

In 2007, as the collection’s national significance became evident, this became the Australian Opal Centre, today run by Jenni, Elizabeth and a board under president, Rebel Black. Many of the centre’s specimens have been gifted by locals, and donations have been encouraged by the federal government’s Cultural Gifts Program, which offers tax concessions.

Great treasures of the world

“The opal fossils of the Australian opal fields are up there with the great treasures of the world,” Jenni tells me on my last day. “Every object in the collection is packed with stories, not just of the ancient life and the geology, but the history and the stories of the miners who discovered these things.” Plans are afoot for a huge underground museum, rather than the current shop front and shed. Although they’ve acquired the site and have a grand plan, millions of dollars need to be raised.

Having a crew of volunteers in the field for a week “has been an incredible boost of energy”, Phil says. “There are not enough palaeontologists in the world and we rely on volunteers to get this work done.”

“Although we’re amateurs, we’re here to do a professional job – to help the AOC develop their stockpile of specimens,” volunteer Ali Calvey tells me. “What they really need are people prepared to get their hands dirty and go out there and find fossils for them – and then help them identify and prepare the specimens. The more we do, the more research can be done.”