Feathered dinosaur tail found in amber

John Pickrell

John Pickrell

In Jurassic Park scientists found mosquitoes trapped in amber that had traces of dinosaur blood and DNA inside them. That was a fictional scenario, but researchers have now found what is, arguably, a much more exciting piece of prehistory trapped inside fossilised tree resin – the tail of a small carnivorous dinosaur covered in fluffy feathers.

Every week or so these days a new species of dinosaur is revealed to the world, but this specimen – dug up by amber miners in in Myanmar (Burma) – has to be one of the most exciting discoveries of the past few years.

I first heard hints of this fossil when I interviewed its discoverer, Chinese palaeontologist Dr Lida Xing, for my book Weird Dinosaurs early in 2016. Since then I have been waiting with great anticipation to the see these images.

Today an international team of scientists – led by Lida, based at the China University of Geosciences in Beijing, and amber fossil expert Dr Ryan McKellar at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Canada – reveal the details of the fossil in the journal Current Biology. What they have found is the tail of a small carnivorous dinosaur – it’s from a juvenile animal would have been about the size of a sparrow.

“Blown away” by the fossil

“I was blown away,” says Ryan of the discovery. “As soon as you look and realise those are individual vertebrae that you’re looking at, and that they have feathers coming off of them, it’s pretty obvious that you’re dealing with dinosaur material. It’s one of those stunning moments when you go ‘holy cow! How did this wind up on my desk?’.”

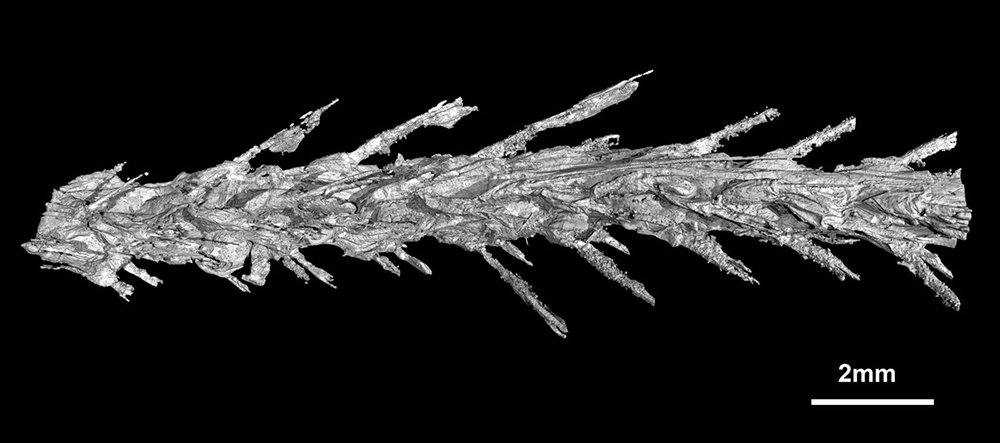

The fossil is made up of eight vertebrae surrounded by mummified flesh and skin – and feathers preserved in three dimensions and microscopic detail, much as they would have appeared 99 million years ago when this animal was scampering through Myanmar’s Cretaceous forests.

This little dinosaur became trapped in amber above the forest floor either while it was still alive, or shortly after it died, but before decay could set into the remains.

The feathers appear to form two keels on either side of the tail; they still retain some colour and it may originally have been chestnut brown on its upper surface and white on its underside. As the tail is long and flexible, it can only be that of a dinosaur, as the bones of modern bird tails are fused into rigid rods or plates known as pygostlyes.

Feathers in amber

Previously isolated feathers have been found in amber which were thought to be those of dinosaurs, but their precise origins were difficult to establish. No other parts of dinosaurs have been found preserved in tree resin before – and although there are many fossils of feathered dinosaurs from China, they are usually compressed nearly flat, making observations of 3D structure difficult.

Lida (who has been illustrating dinosaurs for Australian Geographic since 2010) first spotted the incredible specimen for sale at an amber market in the city of Myitkyina in the Hukawng Valley in 2015.

Many of the remarkable fossil specimens he has found in amber in the last few years were destined for jewellery until he spotted them and recognised their significance. Lida persuaded the Dexu Institute of Palaeontology in Chaozhou, China to purchase the specimen for research.

“Wow, this is like the stuff of dreams!” exclaimed Dr Phil Bell, a dinosaur palaeontologist at the University of New England in Armidale, NSW, when I showed him the images and paper. “There was nothing to say that a dinosaur couldn’t be trapped in amber, but the possibility of it in my mind seemed so ludicrously small, that we would never actually see it.”

“Straight out of Jurassic Park”

“Discoveries like this usually only occur in the movies, and this one is straight out of Jurassic Park,” agreed Dr Steve Salisbury a vertebrate palaeontologist at the University of Queensland in Brisbane.

“Although we’ve known for a while that many non-avian dinosaurs were fuzzy or feathered, details of the nature of their covering have been hard to decipher, mainly because most of the relevant fossils are so squashed. Feathered dinosaur fossils from… north-eastern China are spectacular and clearly show soft-tissue preservation. But with sediments from lake and volcanic deposits, they end up looking like Cretaceous road-kill.”

Phil noted that the fossil is a “fascinating addition” to our understanding of how feathers evolved. It reveals a previously unknown stage in the development of how tiny features called ‘barbs’ formed ‘barbules’ and eventually fused to form a central quill called a ‘rachis’ seen in modern bird feathers. “Being able to see these things in three dimensions just makes the evidence so much more compelling.”

Steve adds that: “discoveries such as this not only provide novel insights into the evolution of feathers, but also highlight the diversity of feather types that occurred in non-avian dinosaurs.”

Baby bird wings in amber

This tail is not the only exciting Cretaceous fossil specimen to come out of the amber deposits of the Hukawng Valley in northern Myanmar. Earlier in 2016 Lida and Ryan published some similarly stunning specimens of baby bird wings and we can expect that in coming years we will see further incredible remains.

Roughly 10 tonnes of amber has been extracted from this one valley in the last year alone, they say.

Preservation in amber is unusual in that it records soft tissues that would normally easily decompose, as well as the 3D shape of these structures.

“This is a new source of information that is worth researching with intensity, and protecting as a fossil resource,” Ryan says. “We are eager to see how additional finds from this region will reshape our understanding of plumage and soft tissues in dinosaurs.”

Sadly – despite the apparent similarities to the scenario in Jurassic Park – the new tail specimen is very unlikely to contain DNA, as genetic material of that kind has never been found in fossils older than a few million years before.

John Pickrell is the author of Flying Dinosaurs and Weird Dinosaurs. You can follow him on Twitter @john_pickrell.