The frog that looks like a turtle

Bec Crew

Bec Crew

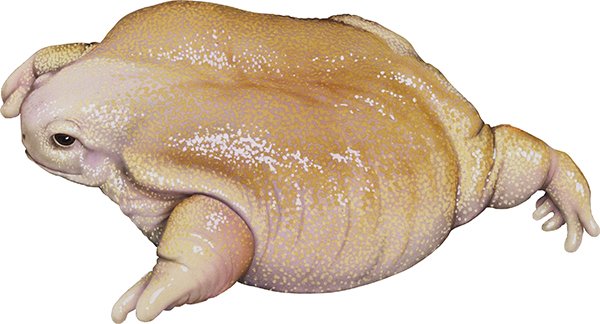

Oh where do I begin? That swollen, bright pink flesh, flecked with gold. Those black, beady eyes and mouth stretched out in a straight line just like a Muppet. That blunt nose and that oddly distinct, unfrog-like head. Those stumpy legs, attached to a flattened body that looks like it’s just slipped out of its turtle shell. Oh and did I mention that it has claws on its legs? No? This swollen pink thing has claws on its legs.

Endemic to Perth in Western Australia, its range extending between Geraldton and the Fitzgerald River, the 5cm turtle frog (Myobatrachus gouldii) is found in sandy soils wherever there are termites to eat and burrowing to be done.

Turtle frogs aren’t like most burrowing frogs from arid regions; rather than using its hind legs to ease itself backwards into an underground hideout, the turtle frog uses its clawed and muscular front legs to dig headfirst into the sand. And it won’t stop till it’s about at least a metre down.

If it’s a female turtle frog, once she gets down there, she’ll be able to lay a clutch of firm, round eggs, sometimes up to 50 of them at a time. And here’s where the species really sets itself apart from many of its peers – the offspring will totally skip the tadpole part of growing up and transition straight from egg to fairly-well-developed tiny frog baby.

(Illustration: Kevin Stead)

Turtle frogs have “unusual sex life”

According to turtle frog expert, Nicola Mitchell from the School of animal biology at the University of Western Australia, this species has “probably the most unusual sex life of all the frogs”.

Talking to ABC radio, Mitchell describes how these frogs engage in courtship behaviours every spring, the males coming up to the surface to call to the females, but they won’t actually mate for another four months after that.

Describing this separation of courtship and mating as unheard of in most frog species, Mitchell adds, “If you want to put it crudely, they may have about a four-month foreplay before they actually mate.”

It’s thought that this strange wait has to do with the frogs needing to mate in the late summer, because their eggs take around two months to develop, and their hatching has to be timed with the rains of winter so the froglets don’t dry out.

So why do they start courting in the spring if that means everything else has to be dragged out?

Just like their young, adult turtle frogs don’t want to risk frying on the surface, so they only leave the safety of their burrows in the spring rain.