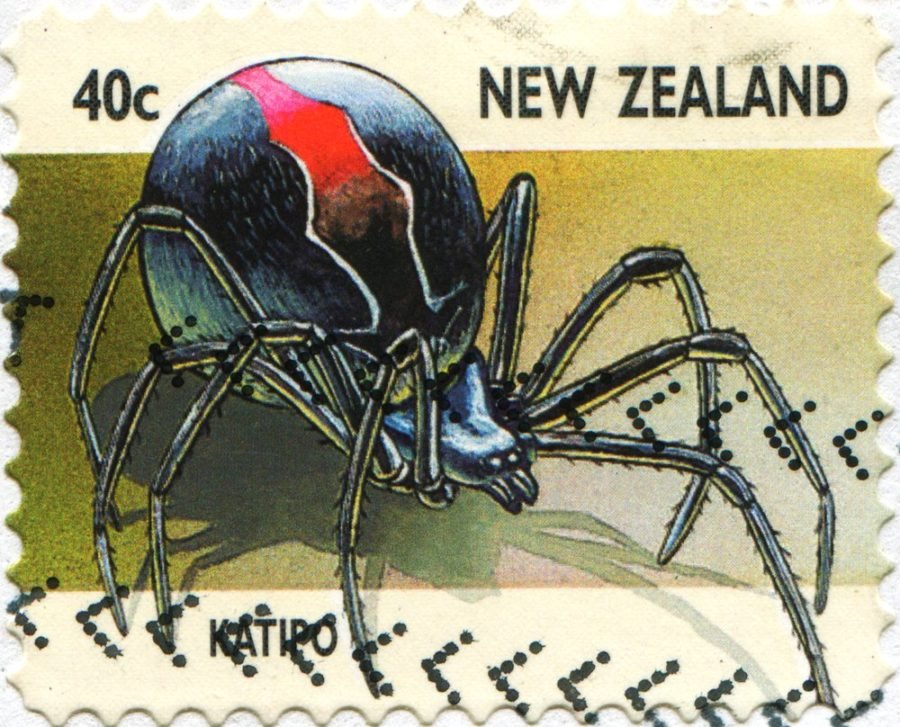

New Zealand’s sole venomous spider is the stuff of legends

Bec Crew

Bec Crew

Here in Australia, we’re feared for our deadly snakes, spiders, jellyfish, and drop bears, but our neighbours across the Tasman Sea have managed to maintain a rare utopia, free from the various nasties that keep some of us up at night.

Well, almost free, because the legendary katipō is the sole native venomous species living in New Zealand, and it’s a small but mighty critter with a bite that can pack a serious punch.

Named after the Māori word, katipō, which translates to “night-stinger”, the Latrodectus katipo spider has gained an almost mythical status in New Zealand, where it’s notorious but rarely seen, and so fiercely protected due to its rapidly declining population, it’s illegal to catch or deliberately kill one.

With just a few thousand katipō left in roughly 50 areas on the North Island and eight on the South Island, these dangerous little beauties are now rarer than a kiwi.

(Image Credit: Jon Sullivan/Flickr)

While their closest relative, the Australian redback spider (Latrodectus hasseltii), makes a nuisance of itself by living in close proximity to humans, katipōs keep to themselves on the seashore, living in driftwood, grass, and discarded bottles and cans on the sand dunes.

Which is of course one reason for keeping your shoes on when you’re exploring the dunes, and if you’re going to leave your clothes and towel somewhere while you swim, just don’t choose the driftwood:

It’s thought that this unique and specialised habitat is the reason for the katipō’s catastrophic decline in recent decades.

Its sand dunes have been shaped and reshaped for decades by agriculture, forestry, and urban development, and invasive grasses and recreational horse-riding and biking haven’t helped either.

It’s a worry, because the katipō is a real force of nature, and to see it endangered is to see a real New Zealand icon under threat.

The females are quite a bit larger than redback females, but they’ve both got very similar markings:

(Image Credit: Jon Sullivan/Flickr)

In fact, these two species are so similar, the katipō was for a time thought to be a redback subspecies.

And similar to its Australian counterpart, when it comes to the katipō, it’s all about the females.

The females grow to be six times larger than the males, and they’re the only ones with the iconic red and black markings – the males are caramel and cream-coloured, and look a whole lot less intimidating.

Seriously, I know which one I’d rather be locked in a room with:

(Image Credit: Arnimactrix/Wikimedia)

Fortunately for hypothetical me in my room of horrors, male katipō spiders aren’t just smaller than the females – it’s unclear if they’re even able to inflict a venomous bite.

While the females do have the capacity to mess up a human with their venomous bite, which can cause a condition called latrodectism, featuring pain, muscle rigidity, vomiting, and sweating, no human death by katipō has been recorded in the past 100 years.

Because these little guys would really rather flee than fight.

If want to hear something almost cute about these spiders, they’ll do practically anything to avoid biting a human. If threatened, a katipō will roll up into a ball, drop to the ground, and run for cover. If it’s cornered, it might even spit silk at its aggressor.

Only as a last resort, if it’s literally getting squished by an unsuspecting bare foot, for example, will the katipō bite. And, well, fair enough.

We’ll leave you with this weirdly charming cartoon of the katipō, which is so strangely adorable, we’re not really sure what to make of it. Team moth?