Check out the melon on the megamouth bee

Bec Crew

Bec Crew

With massive jaws jutting out of an equally massive head, the megamouth bee cuts a rather intimidating figure – for an insect. And while you’d be forgiven for assuming those fearsome gnashers are there for nefarious purposes, the reason these bees have them is actually very sweet.

The megamouth bee (Leioproctus muelleri) was first discovered in 2010 by Dr Terry Houston, curator of insects at the Western Australian Museum, and museum volunteer, Otto Mueller. Found in bushland in the suburb of Forrestdale, about 20 kilometres from Perth, it’s surprising that such a unique species went unidentified for so long.

Unlike honeybees, which congregate in busy colonies in a hive, megamouth bees prefer a more solitary life, just like the iconic blue-banded bee. They spend a good amount of time in underground burrows. In fact, that’s how Mueller first spotted one it was scurrying into its burrow, trying its darndest to disappear.

What’s special about these bees, which are only about the size of honeybees, is that those giant heads are mostly a feature of the males – the females don’t tend to have such oversized features.

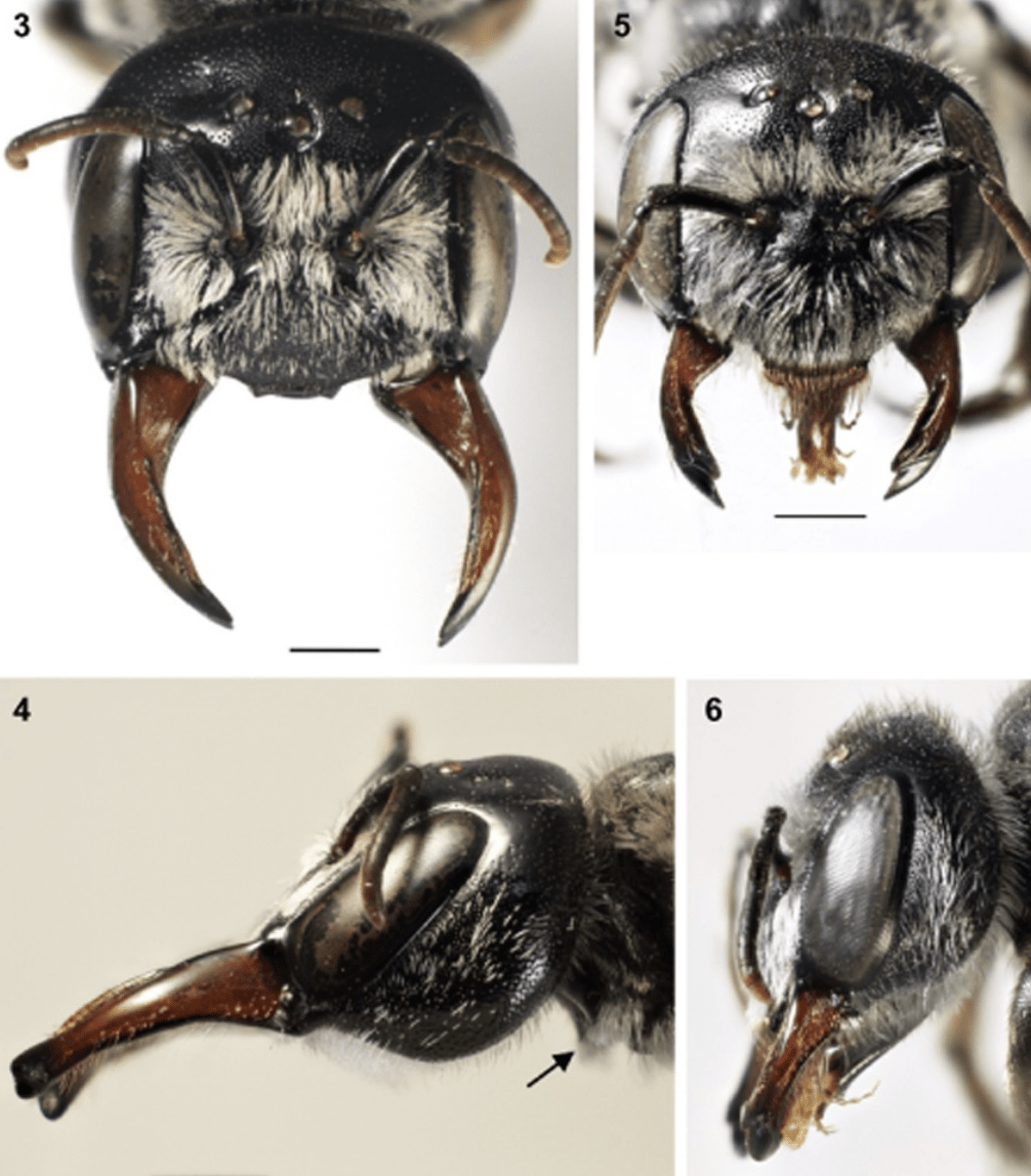

Check out a comparison between the male (3,4) and female (5,6):

On its own, this isn’t all that unusual – in some other species of bees, the males have large heads to help them attract multiple females. But in the megamouth bee’s case, the male’s large head is there to protect the one female he’s chosen to mate with.

These females spend a lot of time in their burrows, tending to their eggs, while male positions himself inside the mouth of the burrow, his head poking up just below the surface. Only the female is permitted to leave and enter– anything else is fiercely fended off by those huge jaws.

“Patrolling males stopped frequently to inspect burrow entrances and occasionally entered, but usually backed out quickly apparently repelled by occupant males,” Houston and his colleague Glynn Maynard, a bee taxonomist from the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry in Canberra, report in a 2012 paper describing the species.

“Skirmishes observed and photographed at nest entrances revealed that fighting males grasp their opponent’s head in their mandibles.”

This not only serves to protect the female and her eggs from rival males, it also helps to protect the eggs from parasites, such as the cuckoo wasp.

Cuckoo wasps infiltrate the nests of other wasps and bees and lay their eggs alongside the hosts’ eggs. Once these eggs hatch, the cuckoo wasp larvae will feed on pollen stored in the nest for the host’s offspring. They might even eat the offspring alive to fatten themselves up. And with that said, I think I speak for all of us when I say, GIVE THE MEGAMOUTH BEE EVEN BIGGER JAWS.