Bats pollinate like bees – and this fruity tropical plant depends on it

Bec Crew

Bec Crew

We’ve heard about the importance of bee pollination – it supports roughly one-third of the world’s food production. But some plants, such as the beautiful Fijian Dillenia biflora tree, cannot live without a very different kind of pollinator: the blossom bat.

Bats are known to pollinate a variety of plant species. And, as you can see in the image above, they do it with nothing but aplomb.

For example, the tube-lipped nectar bat (Anoura fistulata) from Ecuador has an extraordinarily long tongue, which helps it to access the nectar inside the flowers of the Centropogon nigricans plant.

These flowers have petals that grow in the shape of a trumpet and extend for about 9 cm – way too long for most creatures to be able to access the nectar inside.

But with an 8.5-cm-long tongue – about 150% the size of its overall body length – and a slender, elongated snout, the tube-lipped nectar bat has no problem getting a feed from these flowers. In fact, this bat has the longest tongue, relative to body size, known to science. Its tongue is so long, it has to store it inside its rib cage.

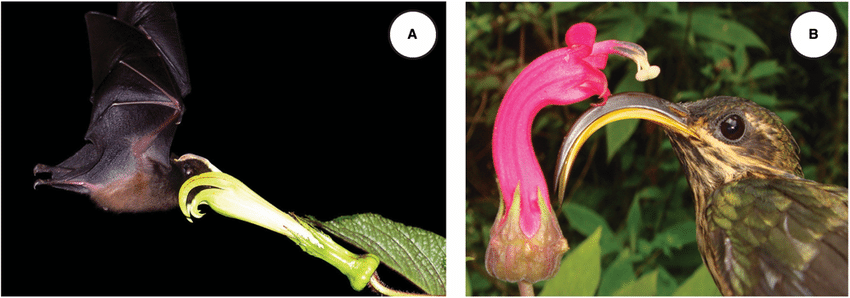

Here’s a tube-lipped nectar bat feed on a C. nigricans flower, alongside a buff-tailed sicklebill hummingbird (Eutoxeres condamini) from South America, with its nectar-siphoning beak:

The Fijian blossom bat (Notopteris macdonaldi) (seen here in the top left corner, looking like it just got caught with its fingers in the cookie jar) might not have the longest tongue in the world, but for it to get its fill of nectar from the D. biflora plant, it doesn’t need to.

The pollen-covered anthers of D. biflora flowers – called kuluva flowers – are covered by an elegant dome of petals. For many years, scientists assumed that this prevented anything larger than a bee from accessing the pollen.

But a world-first discovery, announced by scientists at the University of South Australia, describes how kuluva flowers are actually being pollinated by Fijian blossom bats.

Turns out, these clever little critters have learned to chew through petal dome to effectively ‘lift the lid’ off kuluva flowers and access the goods inside.

And it’s just as well that the blossom bats have figured this out – the researchers found that the D. biflora plant cannot reproduce without their help.

“We discovered that the kuluva flowers never opened on their own, and instead were being pulled off by blossom bats that were after the sugar-rich nectar inside,” says biologist Sophie ‘Topa’ Petit from the University of South Australia, first author of the paper describing the discovery this month.

“The bat lands on a whorl of leaves, removes the corolla, and licks the nectar, covering its nose with pollen in the process. The pollen on the bat is then transported to other flowers of the same species, which are pollinated and produce fruits containing seeds,” says Petit.

“Kuluva flowers have only one chance of being pollinated. Each is mature and receptive for one night only. But because the petals of kuluva flowers are permanently closed, if their corolla is not removed, the flower will die without reproducing.”

Petit and her colleagues have called this new pollination system chiropteropisteusis, taken from the Greek for “reliance on bats”.

We’ll leave you with this video of the lesser long-nosed bat (Leptonycteris yerbabuenae), which pollinates cactus flowers. Let’s just say, tequila-lovers owe a lot to this little bat: