Dr Karl: The truth about Uluru

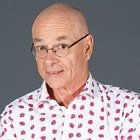

Dr Karl Kruszelnicki

Dr Karl Kruszelnicki

Overseas, Uluru is the essential symbol of Australia. It also has enormous significance to the local Anangu people. The story told to tourists, and to Australian school kids, is that Uluru is the world’s largest monolith. A monolith is a ‘single stone’, so this implies that Uluru is a giant pebble partly buried in the desert sands. But the geologists tell us that this is a mythconception.

The Anangu have known Uluru for tens of thousands of years. The first European here, explorer Ernest Giles, sighted Kata Tjuta from a distance in 1872, but could not get closer, because he was blocked by Lake Amadeus. Another explorer, W.C. Gosse, reached Uluru on 19 July 1873. He wrote, “The hill as I approached, presented a most peculiar appearance, the upper portion being covered with holes or caves…coming fairly into view, what was my astonishment to find it, was one immense rock rising abruptly from the plain; the holes I had noticed were caused by the water in some places forming immense caves.”

Uluru is impressive, rising more than 300m above the surrounding sands, with a circumference greater than 9km. But Uluru is not the biggest Australian rock rising above the local flat plains. Mt Augustus in Western Australia is bigger. Also, Uluru is not a giant isolated boulder, rising from the desert sand. Instead, it’s part of a huge and mostly underground series of rock formations – 100 or so kilometres wide, and perhaps 5km thick. The only parts visible are Uluru, the domes of Kata Tjuta and Mt Connor. Geologists Sweet and Crick write that “the huge vertical ‘slab’ of rock, of which Uluru is but the exposed tip, extends far below the surrounding plain.”

The phrase ‘world’s largest monolith’ makes a nice story for tourists. Just don’t say it near a geologist.

This article was originally published in the Sep-Oct 2016 issue of Australian Geographic #135.