How Aussie scientists used cane toads to confirm pregnancies

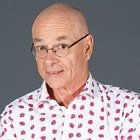

Dr Karl Kruszelnicki

Dr Karl Kruszelnicki

CANE TOADS WERE introduced into Australia in 1935 and by the 1950s were a pest in Cairns. In classic Aussie style, Cairns Base Hospital’s Louis Tuttle and Bill Horsfall found a use for the plentiful amphibians by developing a pregnancy test that used them.

A couple of decades before, in 1928, German gynaecologists Selmer Aschheim and Bernhard Zondek had discovered the presence of a distinctive hormone in the urine of pregnant women. They injected the urine of potentially pregnant women into mice, twice a day for three days then killed the mice 100 hours after the first injection and examined their ovaries. If the scientists could see new blood vessels on the ovaries, they were 99 per cent sure the woman who had supplied the blood was pregnant.

This evolved into the Friedman test for pregnancy, which involved injecting early morning urine from a woman into an ear vein of a virgin female rabbit, aged at least 12 weeks. The rabbit was killed after 36 hours so Its ovaries could be examined: characteristic changes in fern ale organs showed the woman was pregnant. One problem with using mice or rabbits was that they needed to be killed for a diagnosis. Toads, unlike mammals, didn’t.

Tuttle and Horsfall’s test involved separating male and female toads for a few weeks, to ensure the males were not generating sperm. At 9.30am, a woman’s urine sample was injected into the back of a male cane toad and the animal was then examined at 3pm and 5pm on the same day. If it produced sperm, the pregnancy test was positive. The mate toad did not have to be killed and could be used repeatedly.

Soon cane toads were being flown out of Cairns airport to hospital laboratories across Australia. The only down-side was that this didn’t really reduce cane toad numbers.

In 1960 an immunological test for pregnancy was developed. It became available over the counter in Canada in 1971 and its use soon spread worldwide.

READ MORE: