The evolution of Anzac Day from 1915 until today

On the morning of of Sunday, 25 April 1915, Australian and New Zealand troops entered their first major engagement of World War I, stepping into battle on a small Turkish beach – in a moment that continues to ripple through Australian society more than 100 years on.

On that date in every year since, Australians have in some way commemorated the actions of those men on the Gallipoli Peninsula, on a beach that would become known as Anzac Cove.

Looking back at the ways Australians have marked Anzac Day in years gone by offers a frank reflection of changing Australian society and cultural identity over the past century, says Dr Carolyn Holbrook, an historian at Deakin University in Victoria.

“These kinds of myths and legends, they’re a mirror,” she says. “If you want to get a picture of Australian society, you can look at things like this, because they reflect contemporary values.”

1915: The dawn landing

Anzac Cove after the 1915 landing. Image credit: Imperial War Museum/Wikimedia

The first Australians to approach Gallipoli were infantrymen from Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia. In the darkness before dawn, they left the battleships behind in the Aegean Sea and rowed toward the shores of ‘Z beach’. Turkish forces opened fire before the boats reached land, forcing many of the men to launch themselves into the ocean to avoid the onslaught of bullets; the element of surprise lost.

When the survivors from this first wave eventually stepped onto the sand they were sopping wet and disoriented – a state which would propagate throughout the day, and the entire Gallipoli campaign.

By mid-morning around 8000 Anzacs (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) were ashore and had begun scrambling up the cliffs surrounding the beach to battle for the ridges. The day’s actions resulted in minimal gain for the Allies and the Anzacs were forced to consolidate in the cove, with months of fighting ahead.

When the Sun set on 25 April 2015, more than 600 Australians had lost their lives and over 1000 had been injured. The list of the dead would grow to over 11,000 Anzacs by the end of the Gallipoli campaign.

Once news reached Australia that the Anzac troops had entered the war, excitement flowed through communities, and there were murmurings of the birth of the nation onto the global stage at last. The Great War played a definitive role in the formation of Australia’s identity, more so than Federation in 1901.

1916: The first Anzac Day

Australian and New Zealand soldiers marching to Westminster Abbey, London, to commemorate the first Anzac Day, 25 April 1916. Image credit: National Library of Australia

On 25 April 1916, small ceremonies were held around the world and throughout Australia to commemorate the Anzacs’ entrance into the war, and the lives of their fallen comrades. The details of these first Anzac services are slim but historians suggest that services may have taken place in Albany in Western Australia and Brisbane and Rockhampton in Queensland, as well as on the Western Front.

There are also reports of a small service in Egypt, where the Anzac forces had been training before being summoned to Gallipoli one year earlier. Australia and the British Empire were still at war, so while Anzac events in 1916 commemorated those who fought and died at Gallipoli, there was also emphasis on Australia’s pride in entering the war –with continued recruitment in mind.

“It has always been political,” says Dr Martin Crotty, an historian at the University of Queensland. Anzac commemorations have “suited political purposes right from 1916 when the first Anzac Day march was held in London and Australia, which were very much around trying to get more people to sign up to the war in 1916-1918,” he says.

The first dawn services began in the 1920s, driven by returned soldiers and their families, with few other attendees. In the years after the war, “Anzac Day was about commemoration and remembering the dead and fallen mates, combined with a sense of pride for being soldiers and proving themselves,” says Carolyn. “[The day] was very much tethered to the idea of the British Empire.”

Early morning services were solemn, giving way to more upbeat afternoon celebrations, reflecting the pride felt by returned soldiers for their contribution on behalf of Australia to the Great War. By 25 April 1927, all states and territories had legislated for Anzac Day to become a public holiday, and it is believed the first continuous dawn service started in Sydney from 1928.

1960: Anzac Day on the oval

ANZAC Day game between Collingwood and Essendon football teams, 25 April 2011. Image credit: Orderinchaos/Wikimedia Commons

The Anzac Day footy clash between Essendon and Collingwood is a significant event on the Anzac Day calendar, regularly drawing crowds of over 80,000. However, the idea was not always so popular.

All sporting games on Anzac Day were prohibited by the government for 44 years after the first Anzac Day in 1916. The ban was lifted in 1958 on the condition that games would start in the late afternoon, so as not to interfere with Anzac services, and participating sporting clubs would donate to an Anzac Day Proceeds Fund. The first matches were held in 1960.

“There is an analogy between war and sport, people try and resist it, but there is,” says Carolyn. “There’s something about that intense bonding that happens in sports teams, and I’m sure it relates to mateship that happens in wartime where people bond very deeply.”

After the clash each year, one player is recognised for best embodying the Anzac spirit – through ‘skill, courage, self-sacrifice, teamwork and fair play’ – and is awarded the Anzac Medal.

The first Anzac clash between Essendon and Collingwood was on 25 April 1995, an idea conceived by Essendon Bombers coach Kevin Sheedy who said at the time, “We can never match the courage of people who went to war, but we can actually thank them with the way we play this game, with its spirit.”

1960s-1980s: Vietnam protests and social rebellion

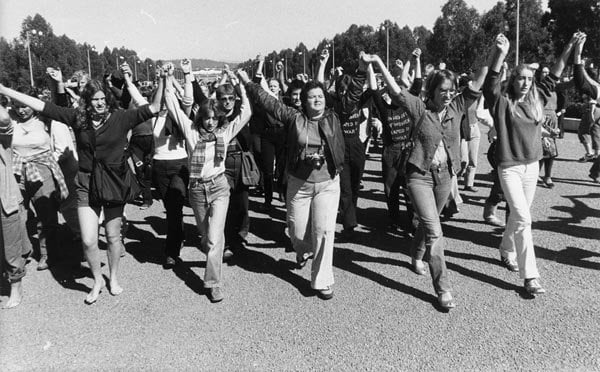

On 25 April 1981, Women Against Rape in War march up Anzac Parade towards the Australian War Memorial to lay their wreath at the Stone of Remembrance. Image credit: courtesy ACT Heritage Library (Canberra Times Collection), by Glen McDonald, 25 April 1981, Ref.008856

In the late 1960s, during the Vietnam War, anti-war protesters used Anzac Day events as a platform to make their voices heard, fighting against conscription and Australia’s military involvement in general.

Over the next 20 years or so, Australians began to overturn society’s established values and start questioning the relevance of Australia’s war connection with the British Empire.

On 25 April 1981, a group of about 500 protesters, mostly women, marched toward Anzac Parade in Canberra. At the head of the procession, women held a banner which read, ‘In memory of all women of all countries raped in all wars’. More than 60 women were arrested by police.

Increased social and sexual rebellion and second-wave feminism led to calls for a new type of comradeship that didn’t discriminate based on sex or race. “The entire meaning of Anzac Day had changed,” says Carolyn.

As numbers dwindled at events throughout the 1980s, it was widely believed that Anzac Day commemorations were on the decline.

1990s: Political rekindling of the Anzac spirit

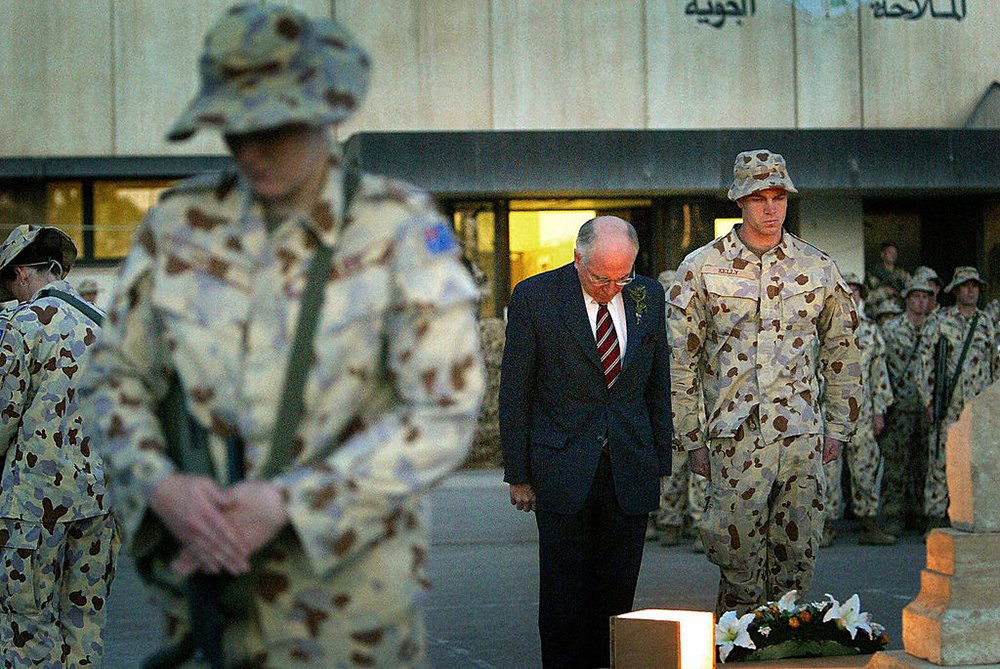

Former Prime Minister John Howard (pictured here in Iraq on 25 April 2004) was a strong proponent of Anzac Day commemorations. Image credit: Kate Geraghty/AFP/Getty Images

On 25 April 1990, Bob Hawke became the first Australian politician to visit Gallipoli, in what historians see as a major milestone in the recovery of Anzac Day.

In the hope of drumming up some nationalism in Australia, and a boost in the polls, Hawke decided his government would pay to take Anzac veterans to Gallipoli for the 75th anniversary of the dawn landing.

After Hawke came Paul Keating – who, according to Carolyn, “was more interested in Kokoda and the Second World War,” than Gallipoli – followed by John Howard. Howard was a huge proponent of Anzac Day commemorations, and visited Gallipoli on 25 April in both 2000 and 2005.

“They sensed that acrimony towards Anzac Day since the Vietnam War was shifting, and they were right,” says Carolyn. Renewed political interest and investment in Anzac Day had the desired effect, and the day of commemoration became popular once again.

This was supported by a controversial push for more Anzac material in the school curriculum, which was quickly labelled as propaganda by critics. The Anzac legend thrived once more throughout the late 1990s and early 21st century.

2010s: WWI centenary and ‘Brandzac’ Day

Woolworths’ ‘Fresh in our memories’ Anzac Day marketing campaign prompted a backlash in 2015, especially on social media. Image credit: @9NewsQueensland/Twitter

The Centenary commemorations of WWI gave rise to a number of questionable Anzac marketing campaigns, the most notorious of which was Woolworths’ ‘Fresh in Our Memories’ campaign in 2015.

The Australian supermarket giant encouraged Australians to contribute photos of people affected by war to a picture generator, which would produce an image with their campaign slogan and the Woolworths logo overlayed. The powerful criticism from the Australian public was immediate and unrelenting. The push back suggested a line had been crossed.

“People don’t blink an eye at [the commercialisation of] Christmas and Easter, but still think that Anzac is sacred,” says Carolyn, who pointed out that Australia is spending more money on WWI Centenary commemorations than any other country.

Some historians believe Anzac Day events are now on the decline, although it’s likely there will continue to be smaller dawn services and official events in the future.

“I think it’s a ritual for older, traditional Australians, [who have] old values of mateship, egalitarianism and loyalty,” says Martin, adding that while older Australians hold on to Anzac Day as a “reaction against globalisation” younger generations aren’t as bothered.

Carolyn disagrees, instead arguing that “it is young people who are responsible for the resurgence, and it’s among older people that there is a big group of sceptics – the Baby Boomers who were heavily influenced by Vietnam War protests.”

“We reached Peak Anzac in 2015 sure, and there has been some backing off since then, but in terms of the dawn services and Anzac Day commemoration, it will remain huge for a good while yet,” says Carolyn. “There is nothing better to take its place in terms of a national mythology.”

A more positive modern adaptation of Anzac Day has been to recognise and commemorate the often overlooked role that women, immigrants and indigenous Australians played in the war. One powerful example being the production Black Diggers, which premiered at the Sydney Festival, telling the stories of the Aboriginal men who enlisted, whose sacrifices were ignored, and who were quickly forgotten upon their return.