On this day: Pemulwuy is killed

Members of Aboriginal communities are warned that this story may contain images and names of deceased people.

On 2 June, 1802, Pemulwuy was killed, bringing an abrupt end to his long-fought battles with encroaching British settlers. Two European colonisers shot dead the Indigenous resistance fighter – an original inhabitant of Toongabbie and Parramatta area, determined to Indigenous ownership of the land.

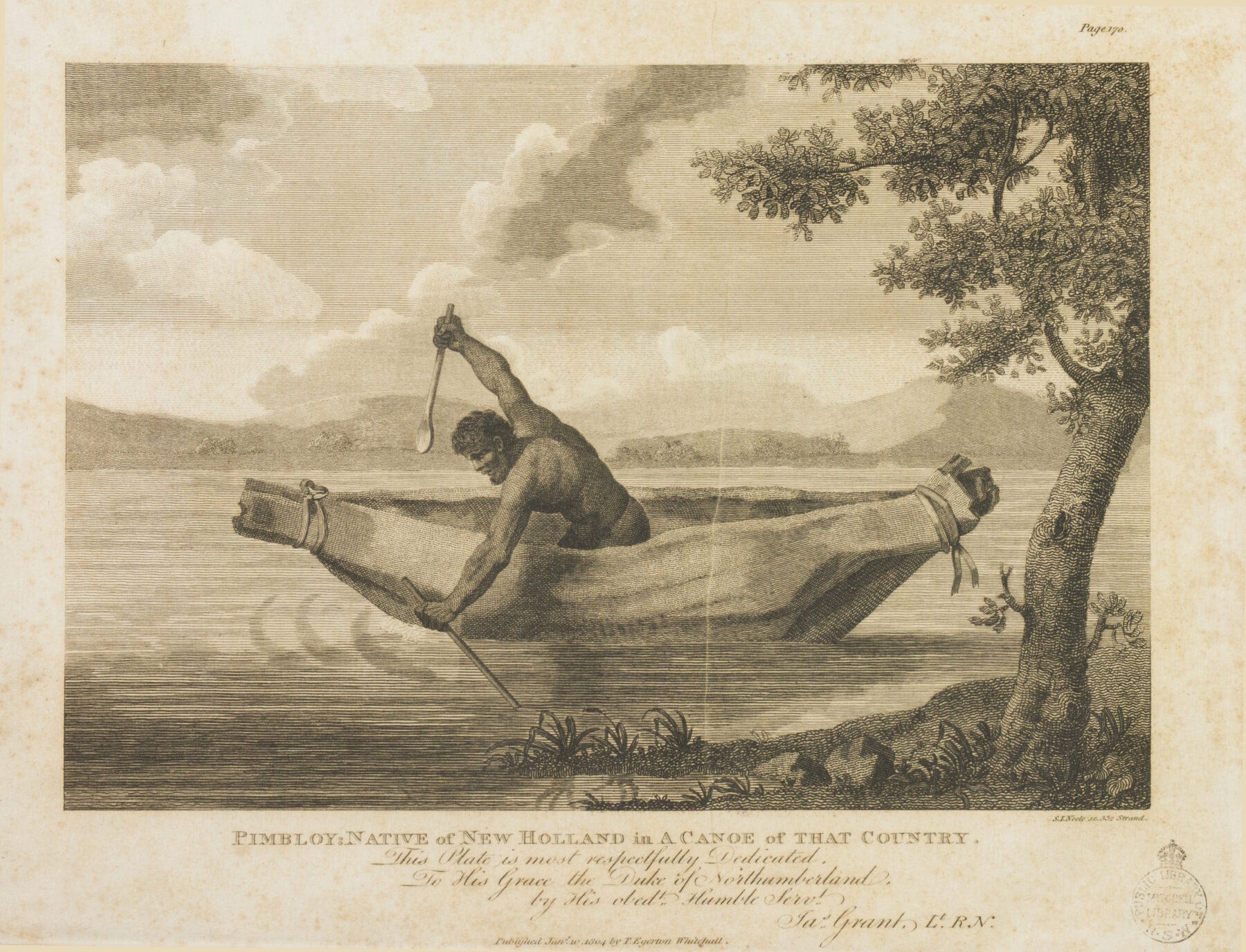

Colonisers had begun to recognise Pemulwuy by his turned left eye, left clubbed foot and the agony of his spear, often decorated in red stone, which brought end to the life of one of Governor Phillip’s companions, John McIntyre. The Indigenous warrior defended the lands of Prospect, Toongabbie, Georges River, Parramatta, Brickfield Hill and the Hawkesbury River, raiding settlers ’ farms and pillaging food and supplies.

Only after the Battle of Parramatta did he find himself in the hands of the colonisers, wounded and immobile. Once he recovered he escaped their grip, leaving these British settlers to believe that he was different from other Indigenous warriors. To them, Pemulwuy seemed impervious to their firearms. One British settler wrote that he had “lodged in him, in shot, slugs and bullets about eight or ten ounces of lead, it is supposed he has killed over 30 of our people.”

The colonisers rejoiced in Pemulwuy’s death. The shooting, labelled “‘Australia’s oldest murder mystery’” by the Sydney Morning Herald in 2003, continues to perplex historians and Indigenous Australians alike.

Mathew Trinca, the director of the National Museum of Australia (NMA) says, “The great mystery is what happened to him? We know that horribly, his head was severed from his body at the time of his death and sent to England but the Museum has searched and others have searched for records of his remains in the United Kingdom in vain.”

The last record of Pemulwuy’s fate exists in the form of a note written by Governor King – a long time enemy of the rebel – to British naturalist, Joseph Banks and, sent alongside Pemulwuy’s head, supposedly embalmed in spirits. “A terrible pest to the colony, he was a brave and independent character,” Governor King wrote.

Up until the late 20th century the story of Pemulwuy was almost entirely written out of history, leaving us to believe that Indigenous Australians succumbed to British rule.

“The story of Pemulwuy over turns assumptions that were made for generations that this land wasn’t fought for by the first peoples. The first peoples of Australia did fight for their land, at different times and different places and they fought hard to preserve their way of life, their culture and their peoples,” says Trinca.

Returning Pemulwuy remains

In 2010, upon a visit from Prince William, there was a renewed call for Pemulwuy’s remains to be returned to Australia’s Indigenous people. There were rumours of Pemulwuy’s head being kept at the Royal College of Surgeons in London.

From there, the remains are said to have been moved to the Natural History Museum, however the museum has no record of this.

The repatriation of Aboriginal remains is a difficult pursuit. Trinca says that repatriation has been a long term goal of the NMA.

“The Museum has a long history of being involved in the repatriation of the ancestral remains of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people over two decades. The importance for any repatriation of any Australian first peoples of this country is absolutely paramount. It’s important for their communities, it’s important for their people to know that they are back in this country and cared for by the people from which he originated.”

The search for Pemulwuy’s remains has proved to be particularly difficult. “If we were able to find Pemulwuy’s remains abroad, I think we should do everything we can to see them repatriated. The problem of course, we simply do not know what happened,” Trinca says, adding, “There are people who feel very desperately about the idea that his remains might be overseas and not interred in the earth of his country.”

Bodies and individual limbs of Indigenous people were exported illegally up until the 1940s. It’s estimated that around 3000 Aboriginal Australians suffered for what was then deemed scientific research. Narrowing down this search to just one single skull has proven impossible.

An historical figure re-interpreted throughout time

Trinca says that reinterpreting Pemulwuy as a historical figure is essential to unseating myths around British settlement.

“There’s no doubt that since the 1980s there’s been a growing awareness of Pemulwuy as a historical figure in the history of modern Australia,” he says.

“I think we’ve come to understand that Pemulwuy represents part of that early history in the making of the Australian nation. It’s a story that shows him to be very much a champion, an advocate and a fighter for his people.”

In 2015 an exhibition at the NMA honoured the Aboriginal warrior for his impact on Australian history, while a plaque was permanently erected bearing his name.

“We placed the plaque in the floor of the museum as a part of our ‘Defining Moments in Australian History’ project that tries to look to those instances in Australian life that we think are important in building our understanding of history.”

Tom Alegounarias, President of Teaching and Educational Standards at the Board of Studies, echoed the importance of these histories in 2016, when he announced dramatic changes to the HSC syllabus that will include the study of Aboriginal historical figures, including Pemulwuy, as of 2018.