A long lost excavation site has been rediscovered, new dino bones found

The discovery of new bones belonging to a dinosaur first unearthed in the 1930s has been announced by a team of Australian and British palaeontologists, decades after the original site was lost.

Their findings were published in Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology.

The remains enhance a collection stored at the Queensland Museum from Austrosaurus mckillop, a specimen from a sub-order called sauropods – dinosaurs known for their long necks and tails and distinguished as the largest land-walking creatures Earth has ever seen.

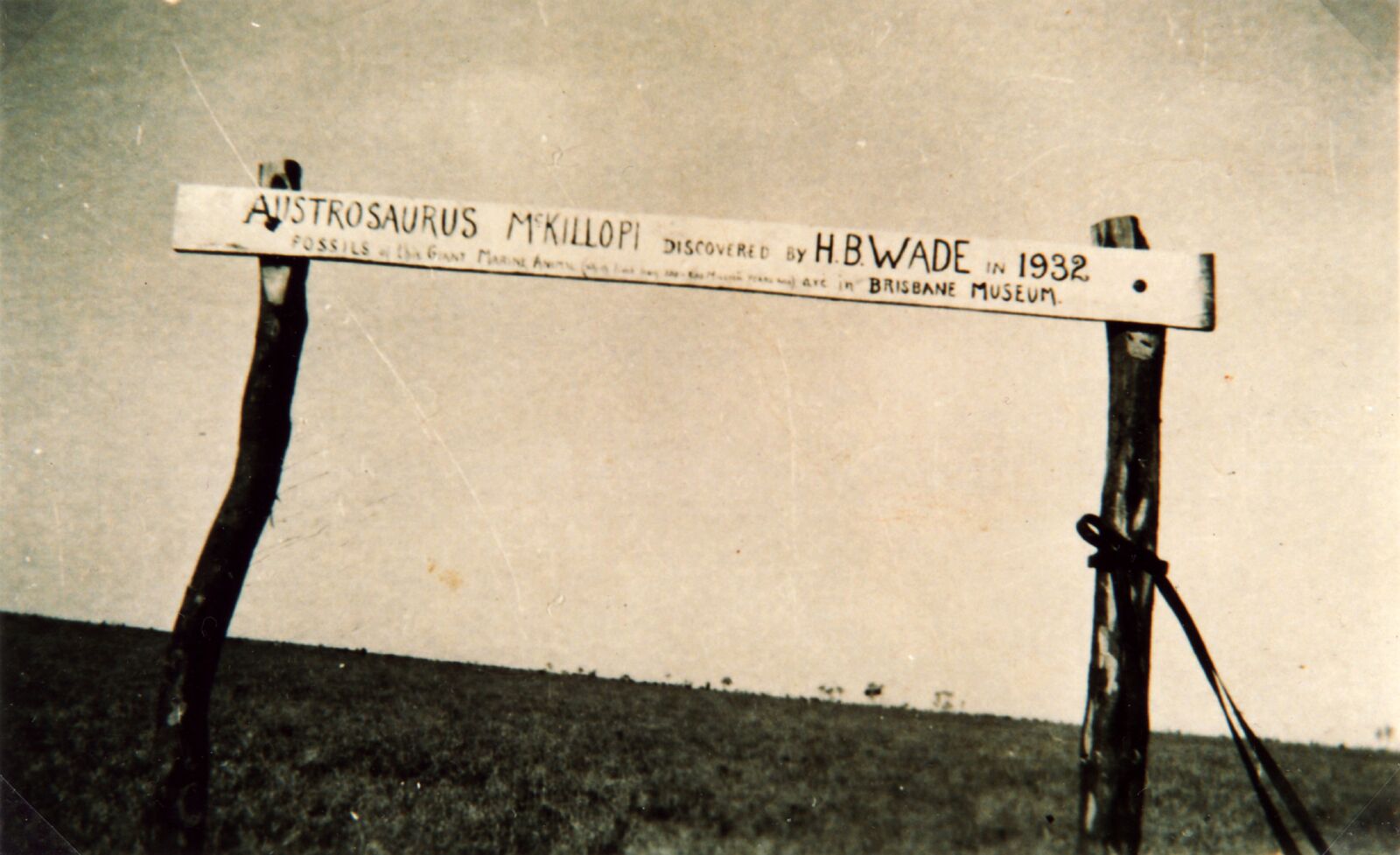

The specimen was first excavated in 1932 at the Clutha sheep station in the Richmond region of Queensland, an area which was under the shallow inland Eromanga Sea during the Cretaceous-period millions of years ago.

Later researchers failed to find the exact site again, despite search attempts in the 1970s and 1990s.

In 2014 and 2015, a team of researchers led by sauropods expert Stephen Poropat of Swinburne University of Technology successfully located the site and excavated a series of ribs and assorted vertebrae dated to about 104 million to 102 million years ago.

The ribs were found aligned in a ‘life position’, meaning the carcass remained largely unmoved after death.

“For these bones to stay in life position, there must have still been skin, muscles, tendons, and ligaments holding them together,” said Caitlin Syme, the team’s taphonomist responsible for examining the decay and fossilization process.

“So then how did this portion become separated from the rest of the body? We proposed that the body was torn apart by scavengers, probably marine reptiles and sharks, with this portion sinking to the sea floor.”

Combined with the bones from the 1932 excavation, Stephen said the new additions provide a much more comprehensive picture of Austrosaurus mckillop, allowing for greater comparisons to other Australian sauropods and further hypotheses about the evolution of the group as a whole.

Tracking down a lost trove

From studying the weathered, originally-excavated remains, Stephen came to the conclusion that the bones made up a portion of the dinosaur’s spine, and that more of the skeleton could likely be found – if only the site were finally relocated.

Stephen told Australian Geographic that his fascination with Austrosaurus began when reading about Australian dinosaurs as a child. Not until 2011 did he dig deeper into information on the site’s whereabouts, and professionally revisit the 1933 scientific report, which included a map of the area with an ‘X’ marking the spots of the original fossil finds.

He used Google Maps to align the historical map with modern satellite imagery and determined an approximate location for the site.

With the help of formerly Richmond-based marine fossils expert Tim Holland and the Richmond mayor John Wharton, who grew up on Clutha, Stephen set out to find the site in 2014. After an unsuccessful ground sweep, John took to the air, scanning the area with a helicopter.

The aerial view revealed two toppled-over sign posts that had once marked the dig site. The discovery of fossils embedded in rocks nearby confirmed the successful search at last.

Despite the significant new finds, Stephen was still a bit disappointed that the long-awaited Clutha site did not turn up slightly more material.

“Part of the shoulder or more of the neck would have been nice,” he said.

The site is now considered exhausted of fossils.

“It’s fantastic that historical research led to the re-discovery of this site, which shows us how important writing and keeping records during field trips are,” Caitlin said.

“Before the 2014 and 2015 digs, we didn’t know that there was more of the fossil out there, and because of these digs we now have a better understanding of decay and fossilisation in the Eromanga Sea.”

The sauropods search continues

But palaeontologists working in Queensland have found even more success recently at a site near Winton, approximately 180km south of Richmond.

Stephen and other scientists are excavating a site originally identified by a local grazier that has been so abundant, it’s considered to likely be the most complete sauropod skeleton ever found in Australia.

Stephen said that the sheer quantity and variety of “Judy’s” bones – “her” neck, ribs, thoracic vertebrae, teeth, and even possible gut contents – allows for even greater study into the dinosaur’s behaviour and the “sauropod family tree.”

“Maybe Austrosaurus was “Judy’s” ancestor, maybe not,” he said. “We’ll have to wait.”

Palaeontologists believe that the greater Richmond area is still rife with opportunity for fossil finds, given all of the Cretaceous-period rocks that could be hiding remnants of the region’s marine history.

Stephen said he aims to continue building off of the slew of recent discoveries.

“Put simply, I hope to understand the evolution of Australia’s sauropods as completely as possible.”