The Endurance22 expedition, organised by the Falklands Maritime Trust, discovered the ship on Saturday 5 March, 100 years to the day since Shackleton, the legendary leader of the 1914–1917 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, was buried on South Georgia in 1922 after dying from natural causes on his way to the sub-Antarctic island.

The 35-day expedition to locate the wreck sailed aboard the South African government’s icebreaking polar supply and research ship S.A. Agulhas II, departing from Cape Town under the command of Master Captain Knowledge Bengu. The expedition leader was Polar geographer and explorer Dr John Shears, and Falklands-born marine archaeologist Mensun Bound was director of exploration as part of a total crew and expedition team of 50.

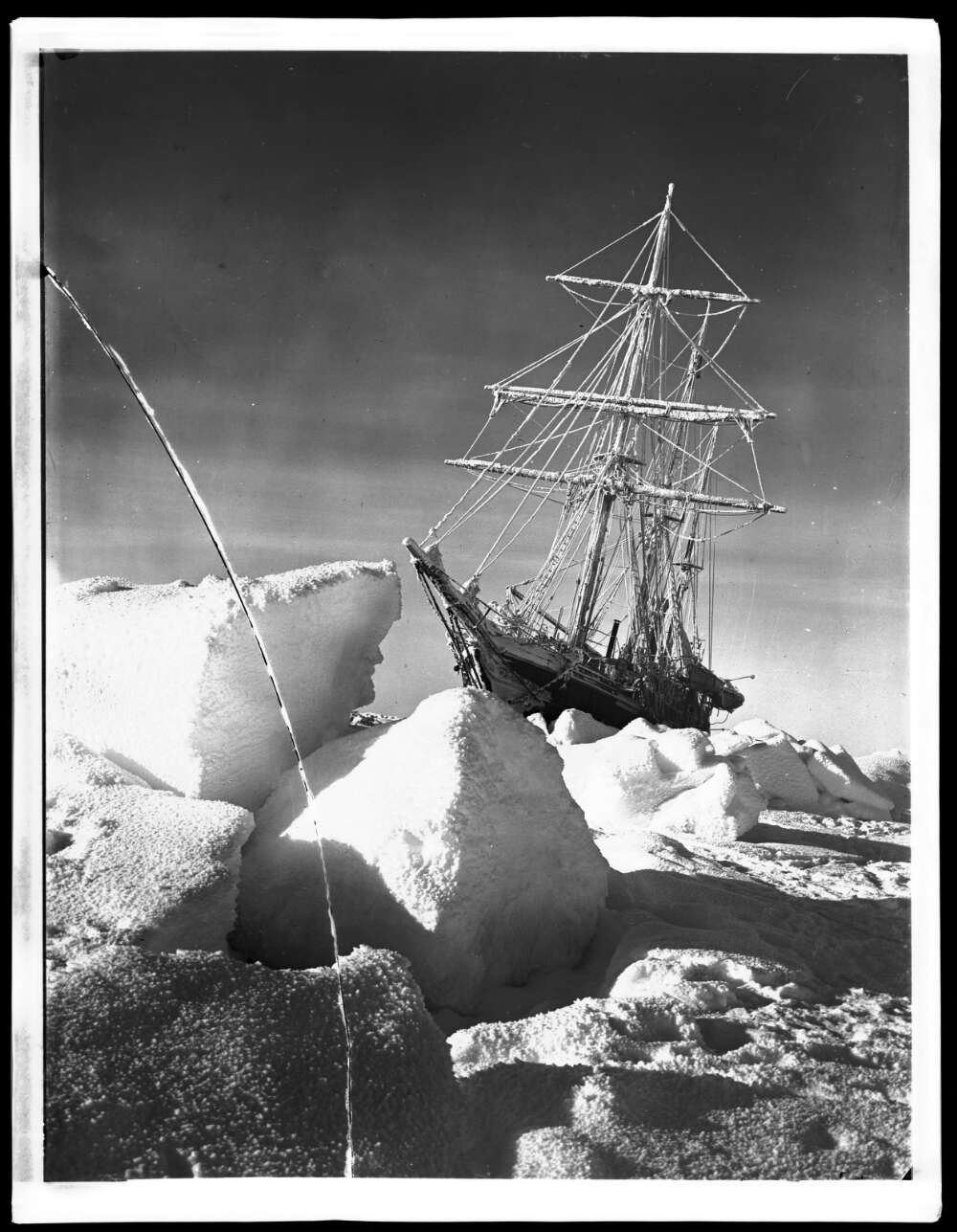

The Endurance was trapped by sea-ice in January 1915, early in Shackleton’s famous 1914-1917 expedition, ultimately leading to the abandonment of both the ship and the attempt to cross the Antarctic continent from the Weddell Sea to the Ross Sea.

The story of the 28-man crew’s escape – dragging cumbersome lifeboats across the ice, followed by a perilous sea crossing to inhospitable Elephant Island and Shackleton’s heroic 1300km sail to South Georgia in a leaky lifeboat – and the subsequent rescue of the stranded men in August 1916 without loss of life is the stuff of legend.

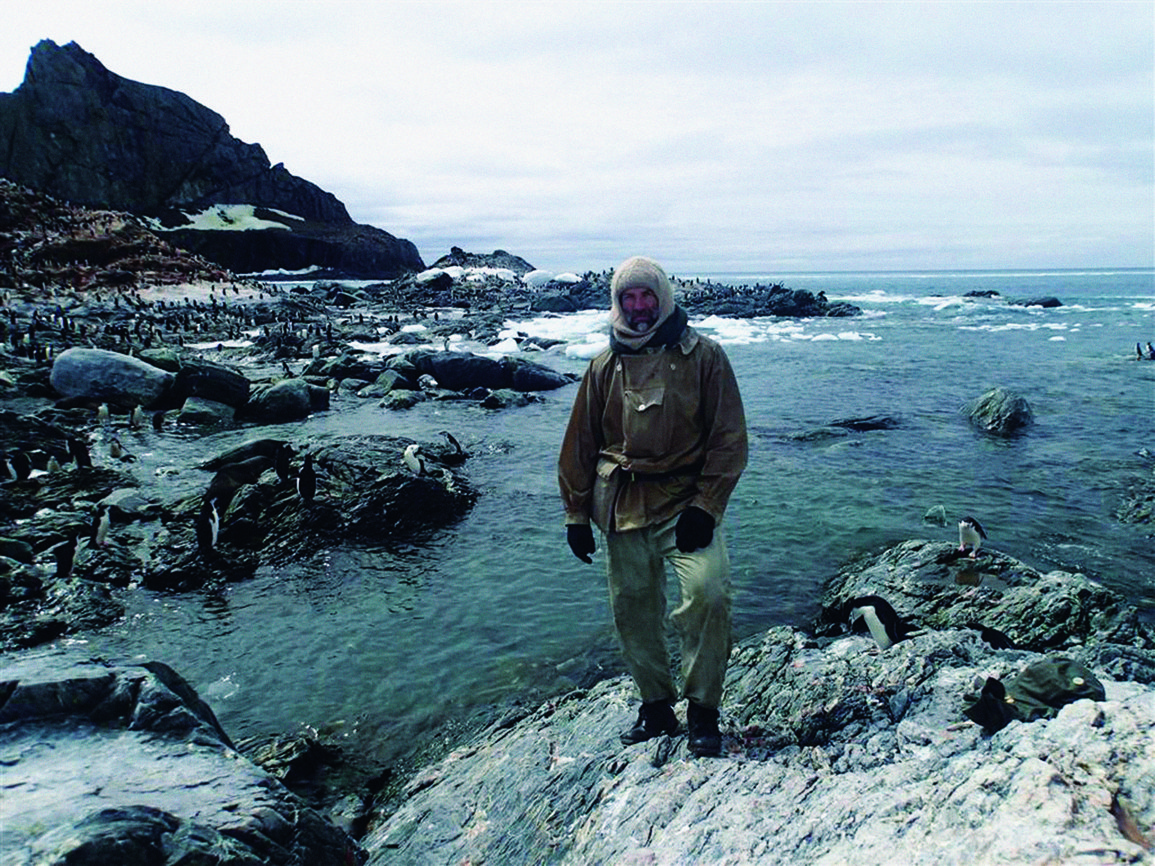

It’s been immortalised in books and on film and, in 2013, Australian Geographic Society advisory committee member and past Adventurer of the Year Tim Jarvis AM faithfully recreated the famous escape.

“I think the discovery of Endurance is incredible at so many levels,” Tim said after the discovery was announced. “The quest to find her speaks to the fact that the spirit of exploration is alive and well and the ghostly images of the ship so well preserved somehow bring us closer to those who sailed on her over a century ago.

“That she has been found also brings closure to some, whilst revealing the story to others who perhaps hadn’t heard it. For me personally seeing the Endurance again is a reminder of the incredible events that unfolded after she sank, and it’s Shackleton’s leadership and the resilience of his men surviving against the longest of odds that are the real legacy of Endurance’s final voyage. In this respect her loss was the start of something far bigger that I have a deep personal connection with, and that I think we have much to learn from.”

Despite sitting on the bottom of the Weddell Sea for more than a century, Endurance is in a remarkable state of preservation with the name of the ship clearly visible in the photographs and video captured by the expedition’s underwater technology.

The name of Shackleton’s ship still clearly visible.

The wreck is in remarkable condition.

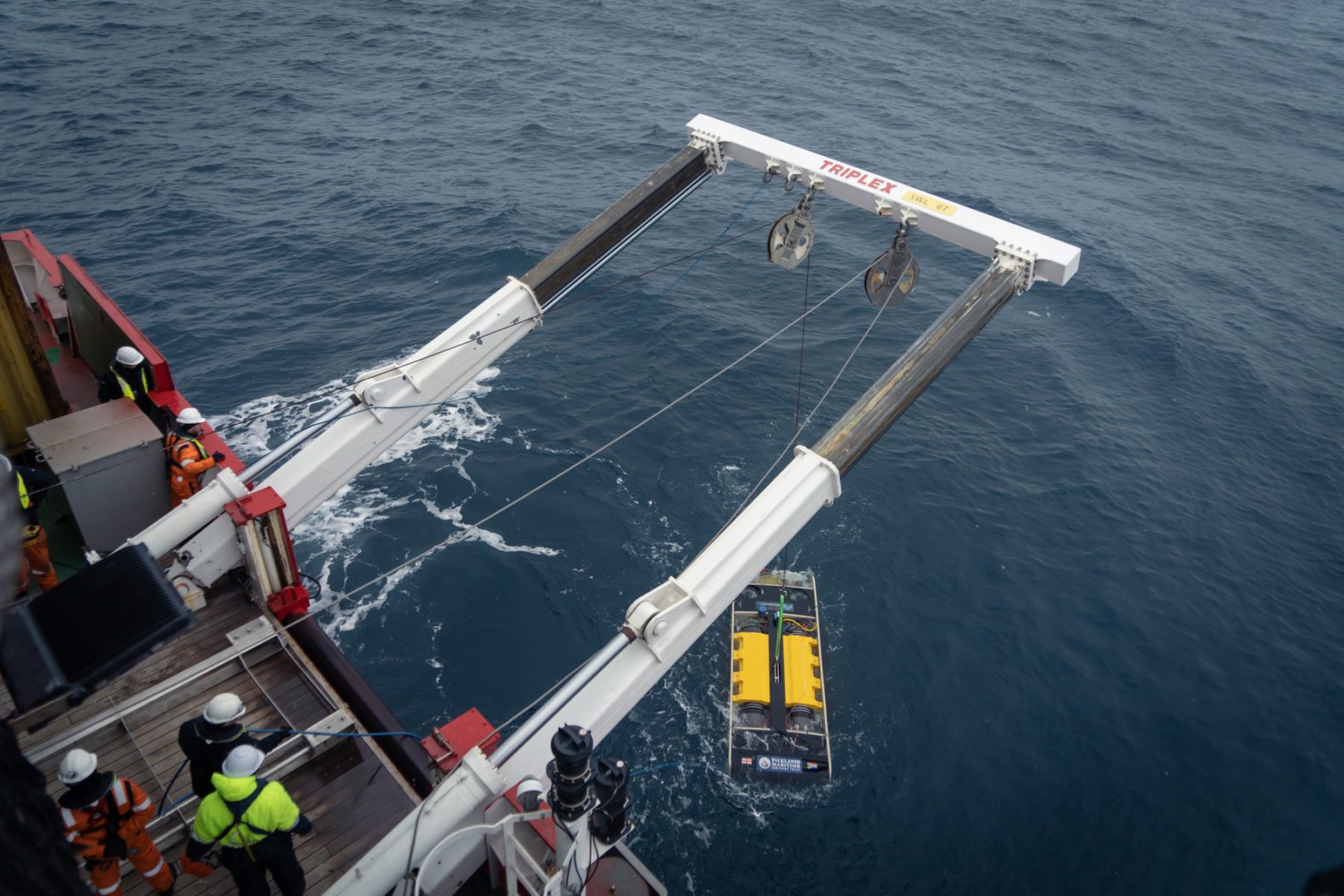

Nico Vincent, manager of the Subsea Project that deployed two SAAB Sabertooth subsea drones from the mothership to explore the wreck, described the difficulties faced by the image capture team working in the same treacherous waters that proved so fatal to Endurance back in 1915.

“This has been the most complex subsea project ever undertaken, with several world records achieved to ensure the safe detection of Endurance,” he said. The hybrid vehicles combine the technologies of Remote Operating Vehicles (ROVs) – always linked to the surface – with Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) – capable of operating without such links and are fitted with high-definition cameras and side-scan imaging capabilities.

According to Mensun Bound, the find is a milestone in polar history.

“We are overwhelmed by our good fortune in having located and captured images of Endurance,” he said.

“This is by far the finest wooden shipwreck I have ever seen. It is upright, well proud of the seabed, intact, and in a brilliant state of preservation.”

The S.A. Agulhas II was built in 2012, a century after Endurance was built.

Dr John Shears, the British expedition leader of Endurance22.

Bound also paid tribute the recordkeeping of Endurance captain, Frank Worsley, whose data helped the modern explorers locate the site, which was just 4 nautical miles south of Worsley’s last reported position.

“The search for the Endurance was 10 years in the making. It was one of the most ambitious archaeological undertakings ever,” he said. “It was also a huge international team effort that demonstrates what can be achieved when people work together. Shackleton, we like to think, would have been proud of us.”

The S.A. Agulhas II left the site on Tuesday and plans to call in at the abandoned whaling station at Grytviken in South Georgia to visit Shackleton’s grave and pay tribute to “The Boss” before heading back to South Africa.

You can read the full story in the May-June 2022 edition of Australian Geographic.