Mysterious marks reveal ‘forgotten’ use of multi-tool boomerang

Apart from hunting and fighting, boomerangs have many functions in the daily activities of Aboriginal communities, including digging, cutting, and making music.

These multiple functions are something Aboriginal people have always known, but the rest of the world has been none the wiser – until now.

In a recently published study in the journal PLOS One, we have “rediscovered” a function of boomerangs in Australian Aboriginal culture – shaping stone tools.

A child’s toy for a tourist

Made from hardwoods, boomerangs are usually shown to return to your hand when thrown into the distance. This common depiction of the boomerang isn’t always true, however.

There is actually a variety of boomerang types, with the returning ones typically being children’s toys used for games and learning. (And, after European incursion, for selling to tourists.)

Most boomerangs are significantly larger than a child’s symmetrical, returning item – this increased size is required for their function as hunting and fighting weapons. But there’s an array of other functions, not all of them widely described in the literature.

We meshed Indigenous knowledge and experimental archaeology to produce scientific proof of a previously unrecognised (to science) use of these iconic objects: the manufacture of stone tools.

Nothing ‘primitive’ about working stone

When we think about stone tools, we associate them with “primitive” technology. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Manufacturing stone tools requires an advanced understanding of fracture mechanics, extensive planning, and years of hands-on practice to produce even the most basic of tools.

Not unlike the contents of today’s kitchen drawers and garden sheds, human groups living in the deep past had access to an assortment of tools for all sorts of everyday activities.

The ability to carefully modify the edge of stone tools was crucial not only to produce the variety of utensils designed, but to resharpen them when they blunted. In modern terms, we can think about butcher knives and bread knives: their blades have different shapes – one straight, the other serrated – each used to effectively cut different materials.

Archaeologists call the careful shaping of a tool edge “retouching” – repeatedly touching (or working) the stone edge until it reaches the shape we want.

Wood shapes stone

For Australia, there is very little published evidence surrounding the retouching techniques used by various peoples across the continent. A deep dive into early European accounts of Aboriginal technologies suggested wooden tools – especially boomerangs – were used to shape their stone technology.

If true, this would be a retouching approach thus far unknown elsewhere in the world.

To investigate this idea, we designed an experiment to discover if boomerangs really could shape stone tools. Most archaeologists would have thought wooden items would not be suitable for such a tough task.

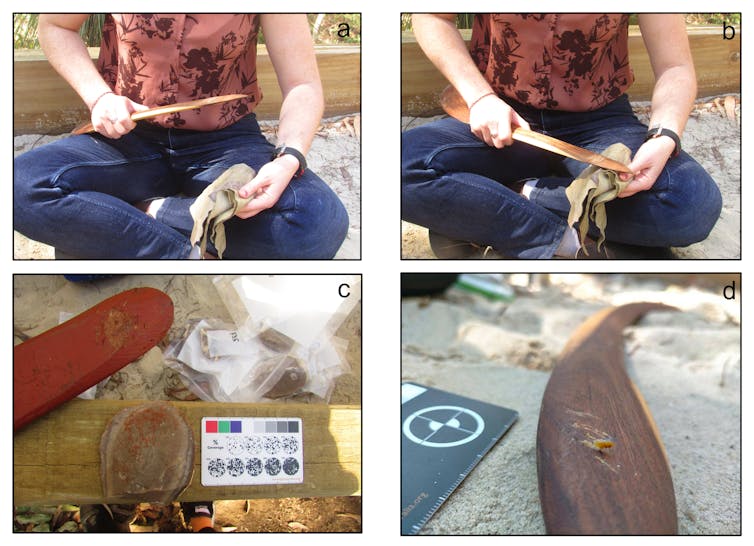

Expert hands infused with Aboriginal knowledge manufactured four hardwood boomerangs to be used in the experiment. These weapons were then put to repeatedly striking stone tool edges. During this process, small, thin pieces of stone detached from the edge – perfectly shaping the stone tool.

The impact of the sharp stone edge against the boomerang’s wooden surface left microscopic marks on the latter. Such marks are not new in archaeology. They have previously been found on bone fragments recovered from prehistoric archaeological sites in Europe dating back as far as roughly 500,000 years ago.

To document these marks, we used a powerful high-definition microscope to get a closer look. A great number of micro-flakes were found to have got stuck within the retouching marks – another trait in common with the bone tools from Europe.

These experimental results allowed us to identify distinctive marks on boomerangs curated by The Australian Museum in Sydney, some of them collected as far back as 1890.

Preserving a diverse and rich past

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples across the country made and used hundreds of multifunctional utensils. Among these, the throwing stick known as “boomerang” sits high on the list.

Our work aims to join Indigenous knowledge and Western-based scientific investigation to explore Australia’s diverse and rich past. Sadly, with the passing of Elders, oral histories and ancient knowledge bases are being threatened.

As communities join with archaeologists in examining artefacts, art, stories, songs, dances, languages, we can learn more about the past and the present. This process is empowering – discovering more about our past and our origins can only strengthen identity.

We are grateful to the Milan Dhiiyaan mob for sharing their Traditional knowledge and supplying bubarra/garrbaa/biyarr (boomerangs) representative of the cultural and spiritual beliefs of the Wailwaan and Yuin people.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of study co-authors Dr Jayne Wilkins and Yinika L. Perston – who is also seen in the video using the boomerang to retouch the stone tools.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.