When the greater glider was listed nationally as endangered in mid-2022 it joined 90 Australian mammals that were either already extinct or at high risk of extinction. For more than a decade there’d been strident calls for the species to be protected, yet logging of the forests where it lives continues. The glider’s listing means almost a third of the 320 land-based mammal species present at the time of European colonisation are now gone forever or are perilously close to disappearing.

In two decades, the glider’s numbers in some regions had fallen by 80 per cent and it had gone regionally extinct in others, with destruction of its habitat a key factor. Extraordinarily, the koala – arguably the most recognisable symbol internationally of Australian wildlife – joined that same inauspicious group of endangered Australian mammals a few months earlier, in February. Again, habitat destruction was blamed as a major cause for its decline.

The listings didn’t shock the country’s ecologists and conservationists, who’ve reluctantly come to regard such things as par for the course. “It’s really concerning that our list of threatened species and ecological communities is not diminishing; it’s still climbing and rapidly so,” says Dr Euan Ritchie, professor of wildlife ecology and conservation at Melbourne’s Deakin University. “Just because a species is listed – or even upgraded, as has been the case for the koala and greater glider – it hasn’t led to significant change for those species in terms of funding or stopping the threats causing the issues in the first place.”

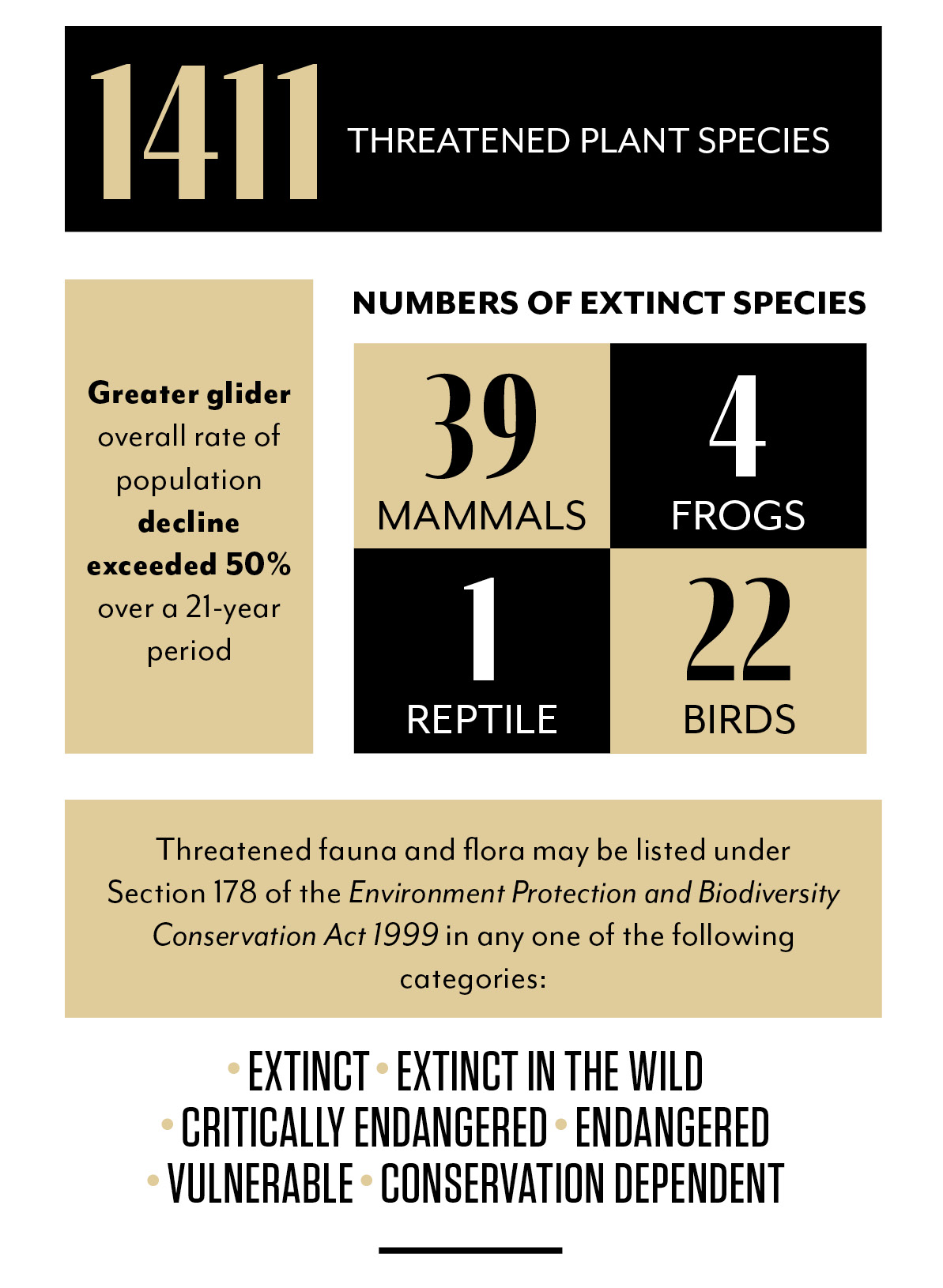

The legal catalogue of conservation status that the greater glider and koala joined this year as endangered is the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) List of Threatened Fauna. Altogether, there are now 562 species of mammal, bird, fish, frog and reptile officially facing various levels of extinction threat on that list. Add plants and invertebrates, and the species threatened with extinction under the Act approaches 2000.

The states and territories have similar catalogues that detail the conservation status of species under their jurisdictions. But the EPBC Act lists of threatened flora and fauna are national registries of particular environmental woe: because so much of Australia’s wildlife is only found here, mostly when a species is entered on these lists as extinct, it’s extinct everywhere – gone from the planet forever. From an international perspective, it’s usually the EPBC Act lists that count.

The legislation was set up at the end of last century to provide a warning system that would trigger a response to safeguard struggling species – a kind of saviour for animals and plants being sucked down the extinction vortex. More often, however, once a species is on these lists it’s tantamount to a death sentence. Very few ever seem to get off. “If governments were doing their job, they’d draw up a recovery plan as a species got listed and invest in and implement that recovery plan. But that’s not happening for scores and scores of species,” Euan laments.

The momentous failings of the EPBC Act were brought to national attention during the previous federal government’s final year with the publication of a detailed review written by Professor Graeme Samuel. Professor Samuel is not an expert in biology or ecology but a distinguished Australian businessman with expertise in the law and a former long-standing chairman of the Australia Competition and Consumer Commission. His report on the EPBC Act was scathing.

“It does not enable the Commonwealth to effectively protect environmental matters that are important for the nation,” the Samuel report found. “It is not fit to address current or future environmental challenges.” The report also criticised a lack of coordination between the federal and state governments where “matters of national environmental significance” were concerned, and it found that current laws failed to support good environmental outcomes.

“The overall result for the nation is net environmental decline, rather than protection and conservation,” the report said. “Significant efforts are made to assess and list threatened species. However, once listed, not enough is done to deliver improved outcomes for them.” The EPBC Act, the report concluded, “needs fundamental reform to ensure that future generations can enjoy Australia’s unique environment, iconic places and heritage”.

The previous government controversially set aside the report and ignored its recommendations. But the new federal government has promised a considered response by the end of the year. Although that’s been roundly welcomed by ecologists, many remain unconvinced the new government has shown it will take the steps needed to halt Australia’s extinction crisis. And the release of its 2022–2023 Threatened Species Action Plan: Towards Zero Extinctions in October did little to ease the concerns of many.

Responses from senior scientists to that plan ranged from cautious optimism to angry scepticism. Key targets in the plan include: the prevention of new extinctions; the addition of 10 threatened species at imminent risk of extinction to the 100 priority species list; 14 new priority mainland places and six priority islands for protection; the protection and conservation of more than 30 per cent of Australia’s land mass; and increased participation of First Nations people in land management for conservation.

“Most ecologists and conservationists would say it’s nice to hear more positive ambition [from the new government] and there has been marginal improvement, but it’s marginal at best. There’s a lot of greenwashing going on,” Euan says, citing ongoing federal approval for fossil fuel ventures and projects that destroy key species’ habitat. “It’s well and good to say you love wildlife and be photographed cuddling koalas, but if you’re still approving the destruction of their habitat, if you’re still committing to fossil fuel use…it’s very hard to see how those things are aligned with a zero-extinction ambition.”

If Euan is disappointed, then Dr David Lindenmayer, professor of conservation biology and forest ecology at the Australian National University, is unreservedly furious about the country’s ongoing slow call to action on disappearing species. David, who has arguably published more in this area internationally than any other Australian expert, is underwhelmed by the new plan.

“I’ve seen this so many times before – glossy documents with nice photographs,” he says, while questioning the level of funding allocated to support the plan and the appreciation of how dire the crisis is. “I mean just look at the State of the Environment report – it’s horrible!” The latest version of that report, released in July 2022, found that: the nation’s environment is deteriorating; Australia’s number of threatened species had risen by 8 per cent since 2016; more extinctions were expected in coming decades; climate change is increasing pressure on every ecosystem; and Australia now has more foreign plant species than native.

David decries the level of government funding committed to saving species. And that was a recurring concern raised in the documented responses from most of his colleagues to the release of this latest Threatened Species Action Plan. “It’s widely seen as exceedingly disappointing and extremely frustrating that the government has only allocated a pitiful $225 million to their save-nature program,” Euan says.

In 2019 some of Australia’s most senior conservation scientists, headed by the University of Melbourne’s professor of ecosystem and forest science, Brendan Wintle, published a paper in the international journal Conservation Letters that estimated Australia would need to commit at least $1.7 billion a year to address the nation’s extinction crisis. The paper attempted to put this in context: “Although governments may consider this to be a large sum relative to current levels of funding, a useful context is that Australians will spend more than double this amount on pet cat care in 2019, the Australian government expects to pay $191.8 billion in social security and welfare payments in 2019–20, and forewent [sic] $980 million tax revenue through fuel tax credits to coal mining companies in 2018.”

Dr Martine Maron, a professor of environmental management at the University of Queensland (UQ), and one of many co-authors on that paper, says government reaction to the sort of figure suggested was that it is “unimaginably high” and “a government couldn’t possibly meet this cost; it has to be private industry”.

“But that’s just not true!” Martine says. “Australia has accepted crumbs for biodiversity conservation for far too long. This is our very life-support system, the costs we are talking about are nothing in the context of government budgets. It’s all about priorities and it’s all about will, so we need those sorts of investments and there is no way around that.

“I haven’t seen commitment to taking nature conservation seriously for a long time now on either side of politics. And so the sorts of drivers that are causing the biodiversity crisis continue unabated and in many cases are getting worse.”

The EPBC Act lists 29 Australian fish species as either endangered or critically endangered. White’s seahorse (Hippocampus whitei) is one of them. It’s threatened mainly by the loss of its habitat in eastern Australia. Image credit: Clay Moran

The most recent reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) strongly advise that the answers to both climate change and biodiversity loss are inextricably linked. Saving species also means mitigating climate-change effects. There have also been multiple reports quantifying other values of species’ conservation, from financial to improved human health.

Queensland’s former Chief Scientist, Professor Hugh Possingham, now at UQ, agrees there are enormous benefits, both tangible and intangible, to be gained from rescuing the nation’s species from extinction. “Australia’s plants and animals are a big part of the tourism economy,” he says. “People pay a lot of money to see our birds, coral reefs and wild places, and the more we lose, the fewer tourists we attract. Furthermore, there is increasing scientific evidence that healthy environments make healthy people and even just exposure to a diversity of life – things like birds, trees and flowers – improves people’s mental and physical health.”

It’s not only loss at a species level that is the issue. “The abundance of common species is also substantially down,” Hugh says. “So it’s not just that we’re losing endangered and threatened species, there are declines in many common species like willie wagtails as well. So there’s an extinction crisis and an abundance crisis.”

He also points out that Australia has particular responsibility on the world stage to safeguard its species because some 85 per cent of our fauna and flora is found nowhere else. So the number of species is important, but so too is its unusual nature. “If you look, for example, at our mammals and our birds, they are so different from the rest of the world,” Hugh says.

Australia’s commitment to turning around its extinction crisis will be on show to the world in Montreal, Canada, in early December 2022, at the COP15 meeting – one of the most anticipated international meetings on biodiversity conservation in more than a decade.

It’s similar to the Glasgow COP26 climate-change conference in October 2021, but with biodiversity conservation as its focus. At its core will be what’s known as the post-2020 global biodiversity framework (GBF). The draft GBF has goals to be achieved by 2050 and milestones to be achieved by 2030.

“The goals include very important outcomes such as increases in the extent and condition of ecosystems and a reduction in species extinctions,” Martine says. Australia agreed to 20 targets at COP15’s precursor, COP10, in Aichi, Japan, in 2010, and fell short of achieving most, if not all, of the targets. But then so did much of the world. This time around, the stakes are considerably higher.

“We lead the world in mammal extinctions, we’re one of the highest land-clearing countries in the world, we’re still opening up coal and gas mines and we’re still logging native forests –

we’re still doing all sorts of really dumb, stupid things,” David says. “I think unless something seriously changes in terms of investment then we’re going to be seen to be the frauds that we are.”

Martine agrees. “But if the actions line up with the rhetoric, then I think things will be looking much rosier,” she says.