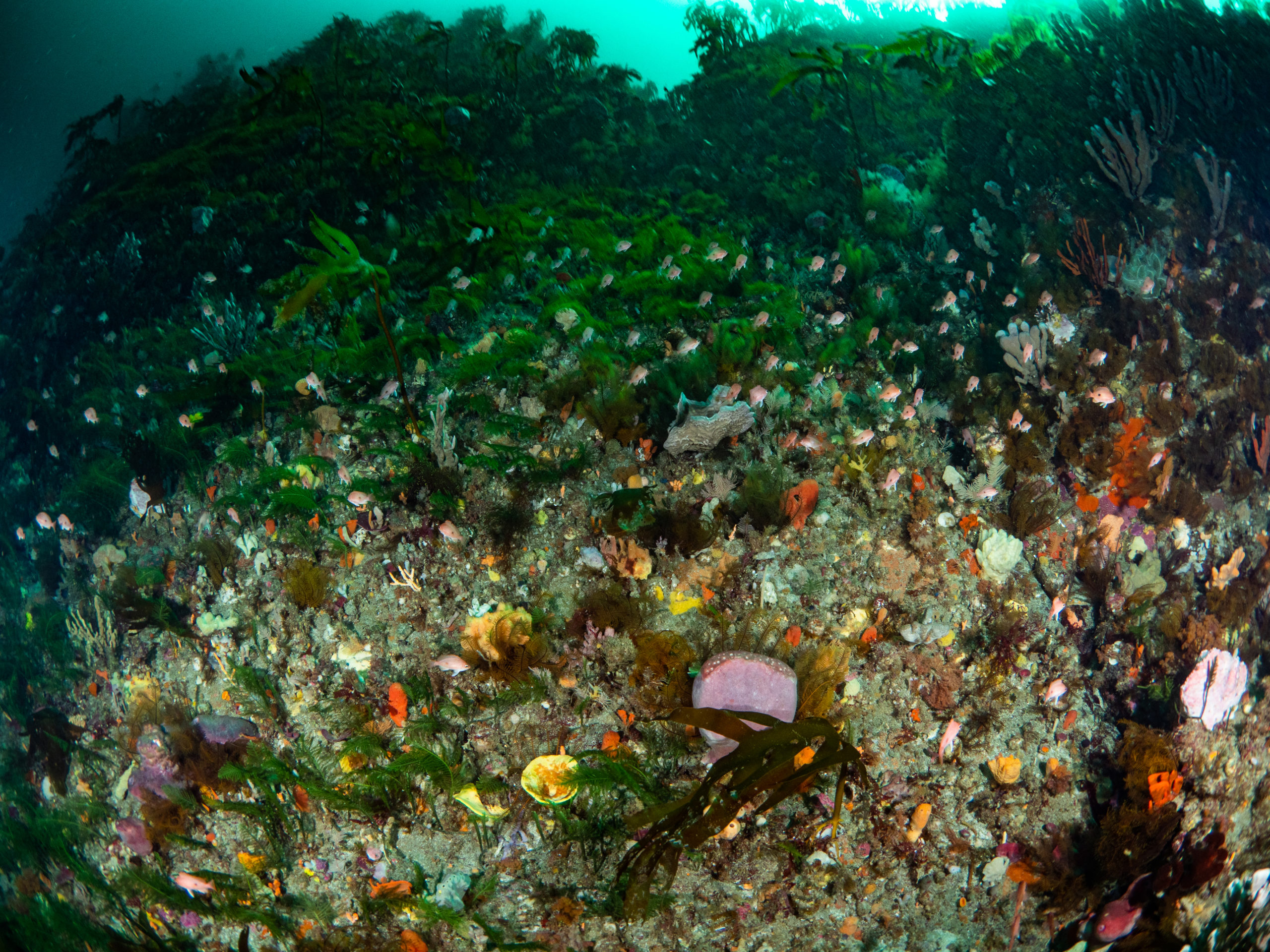

‘Better than the Great Barrier Reef’

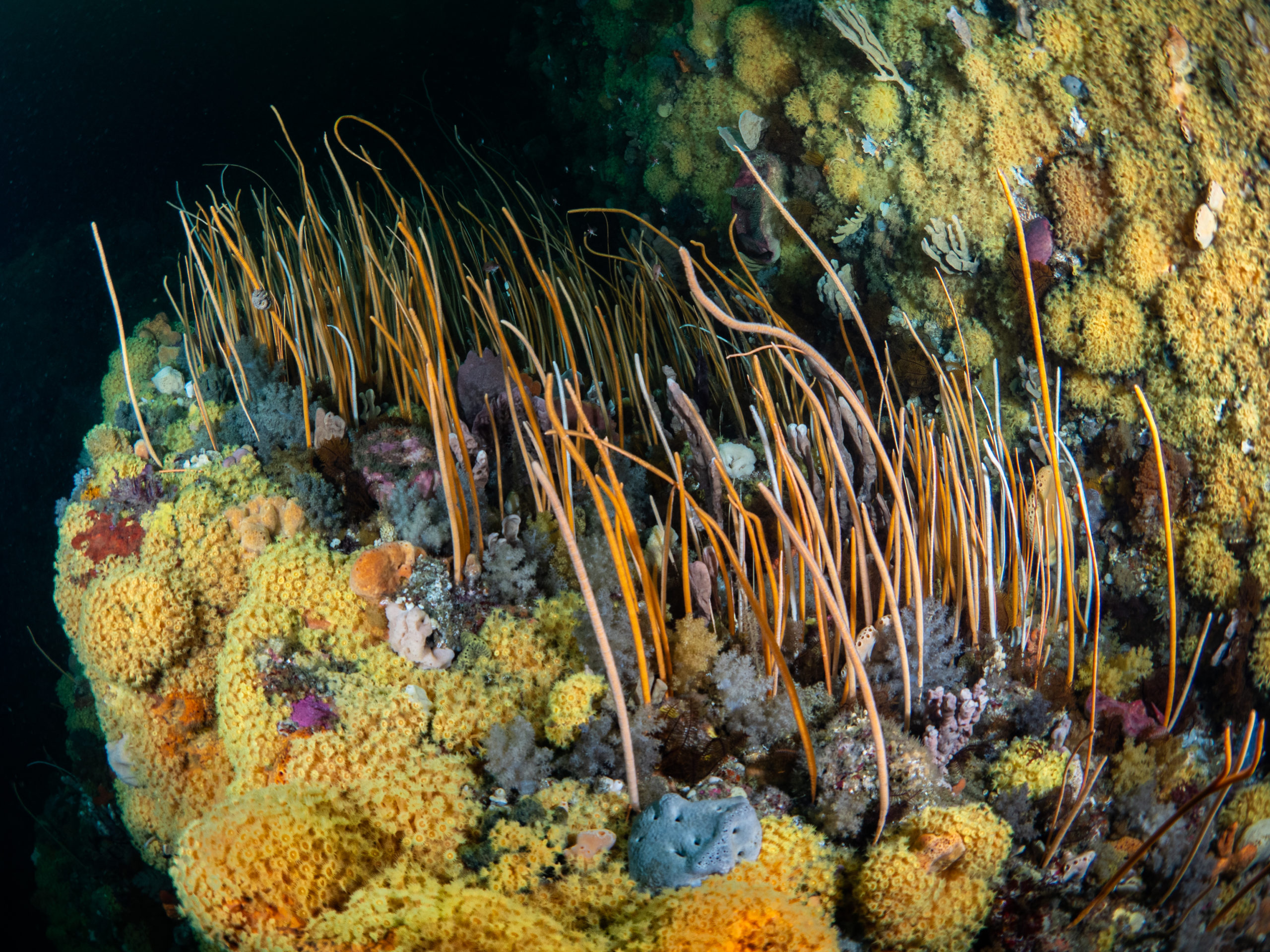

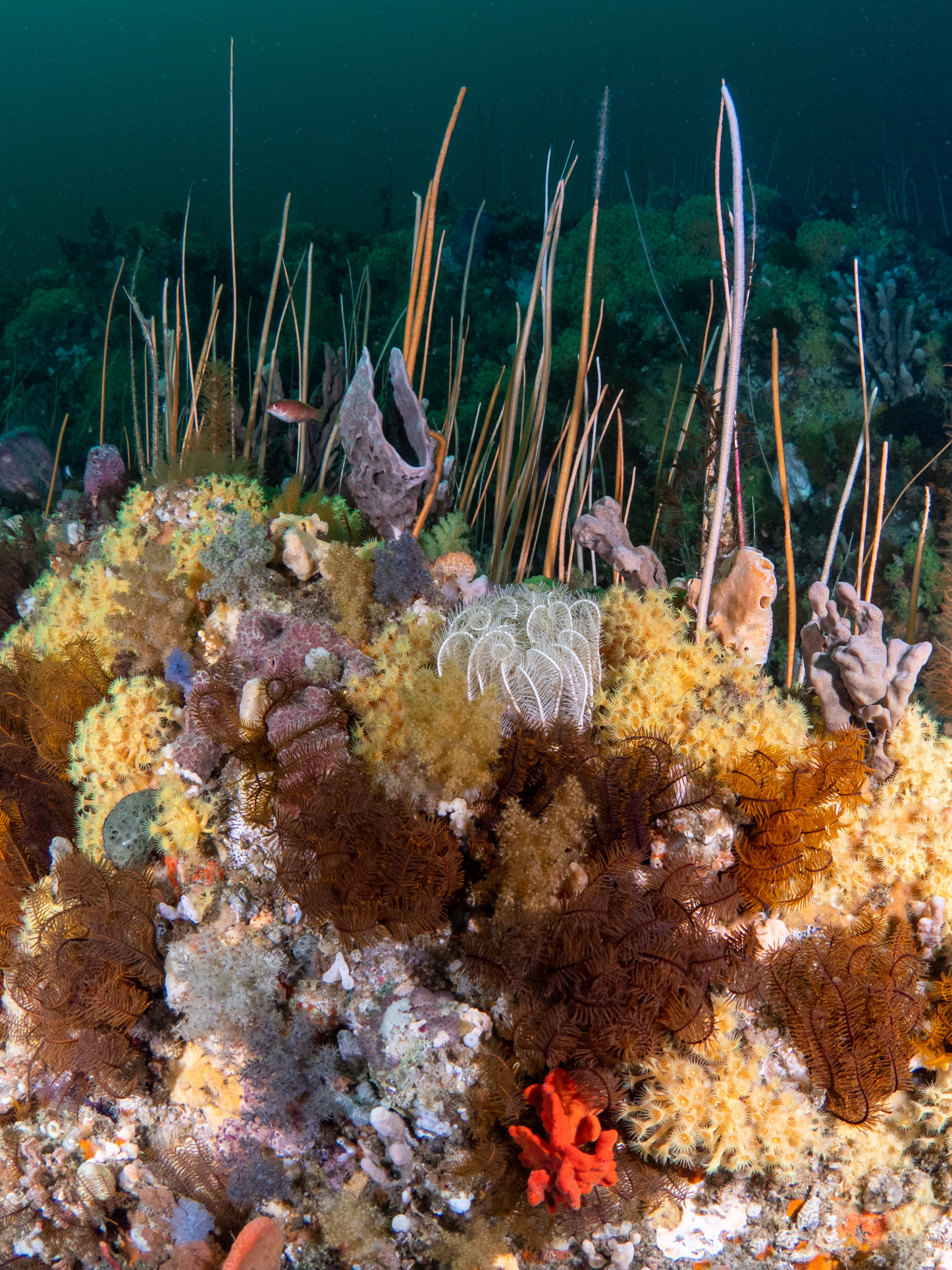

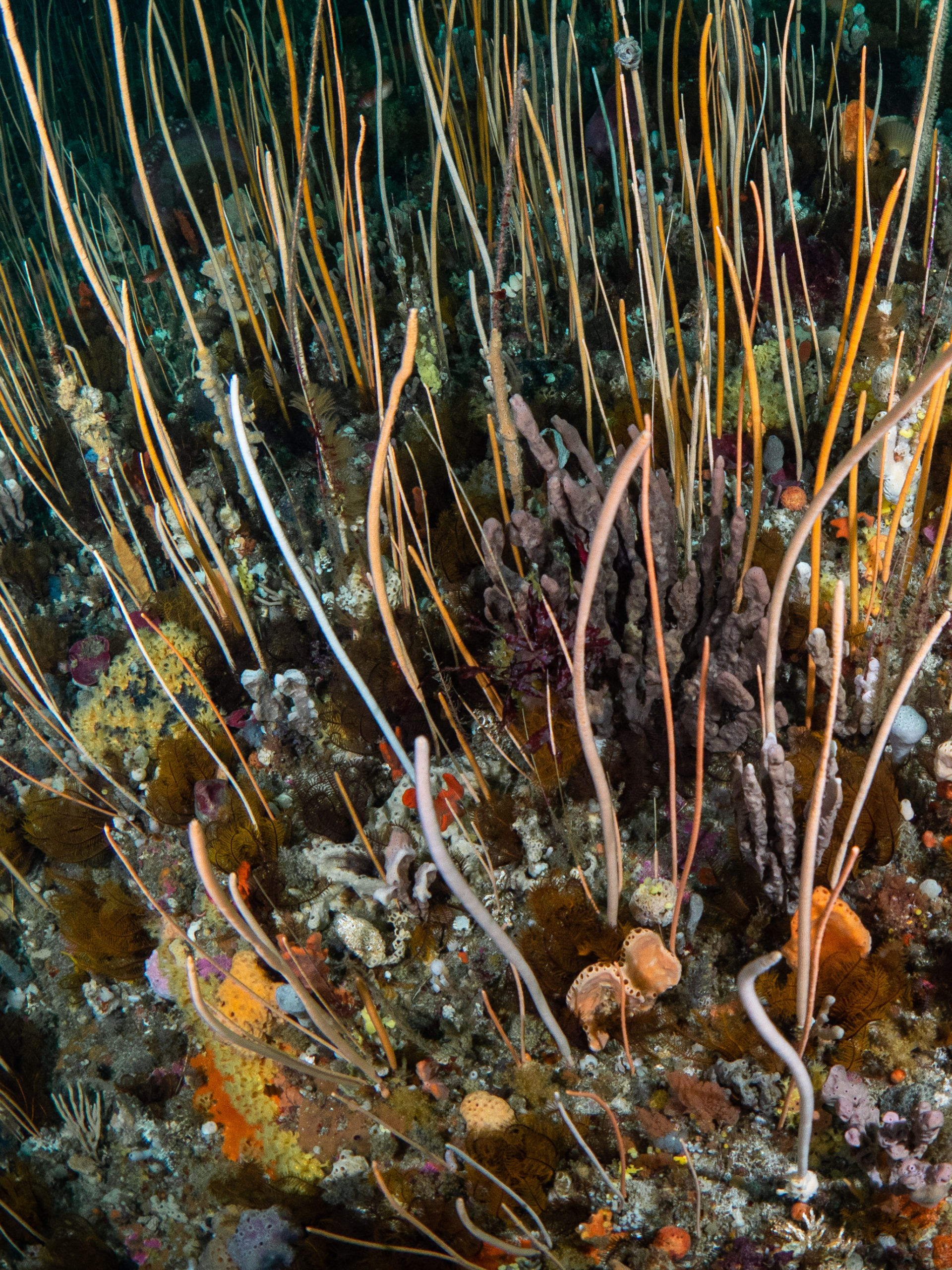

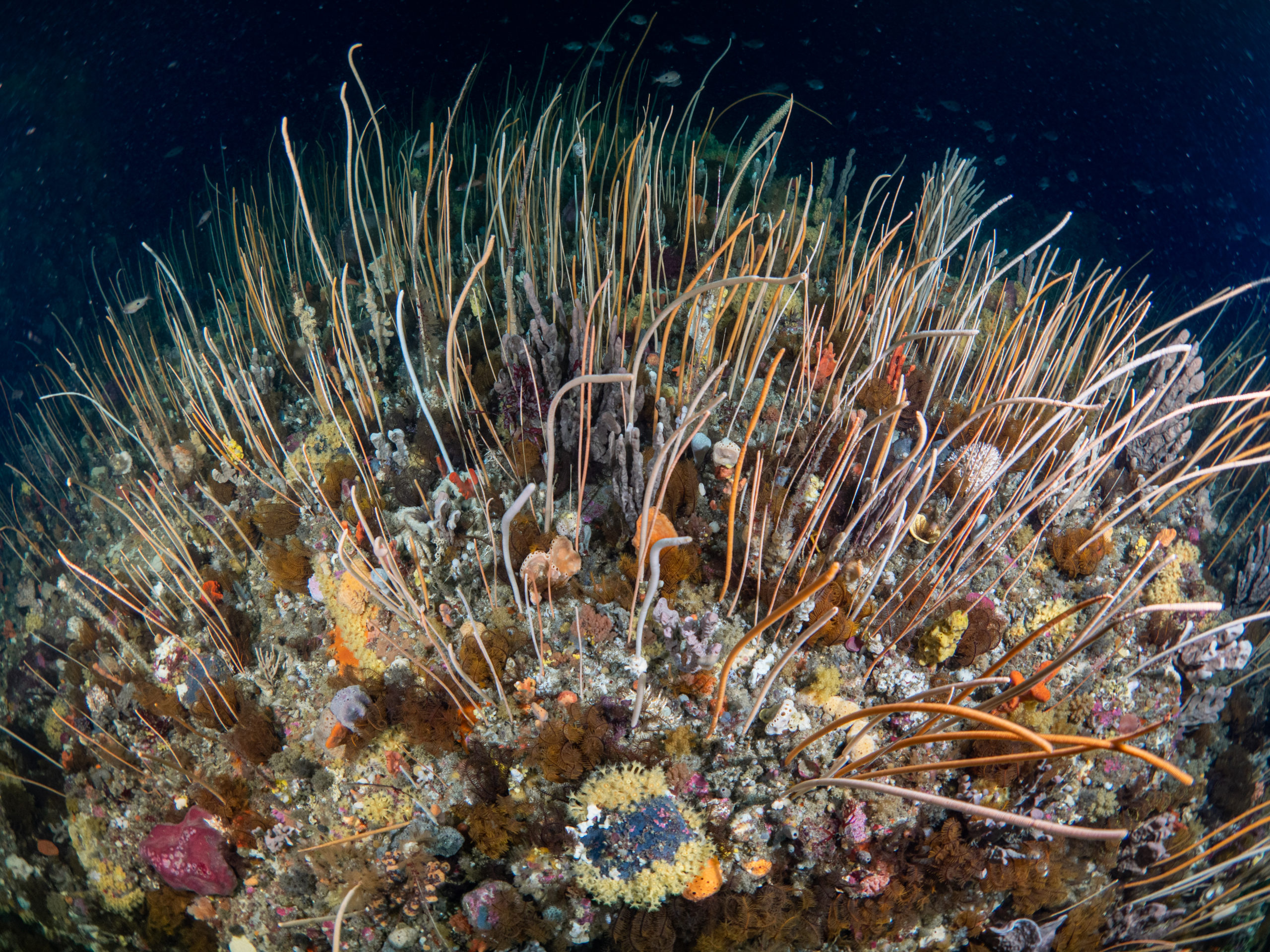

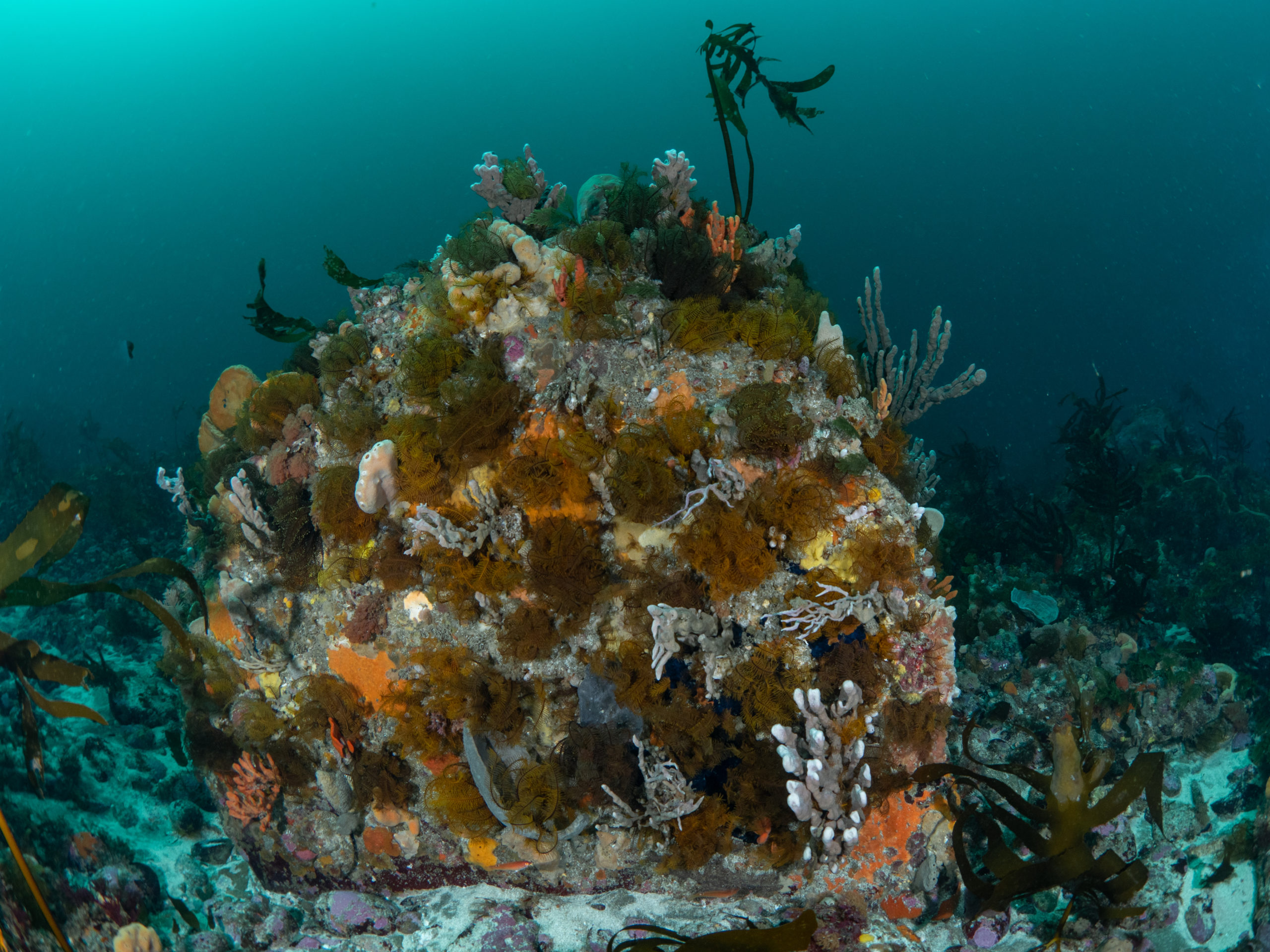

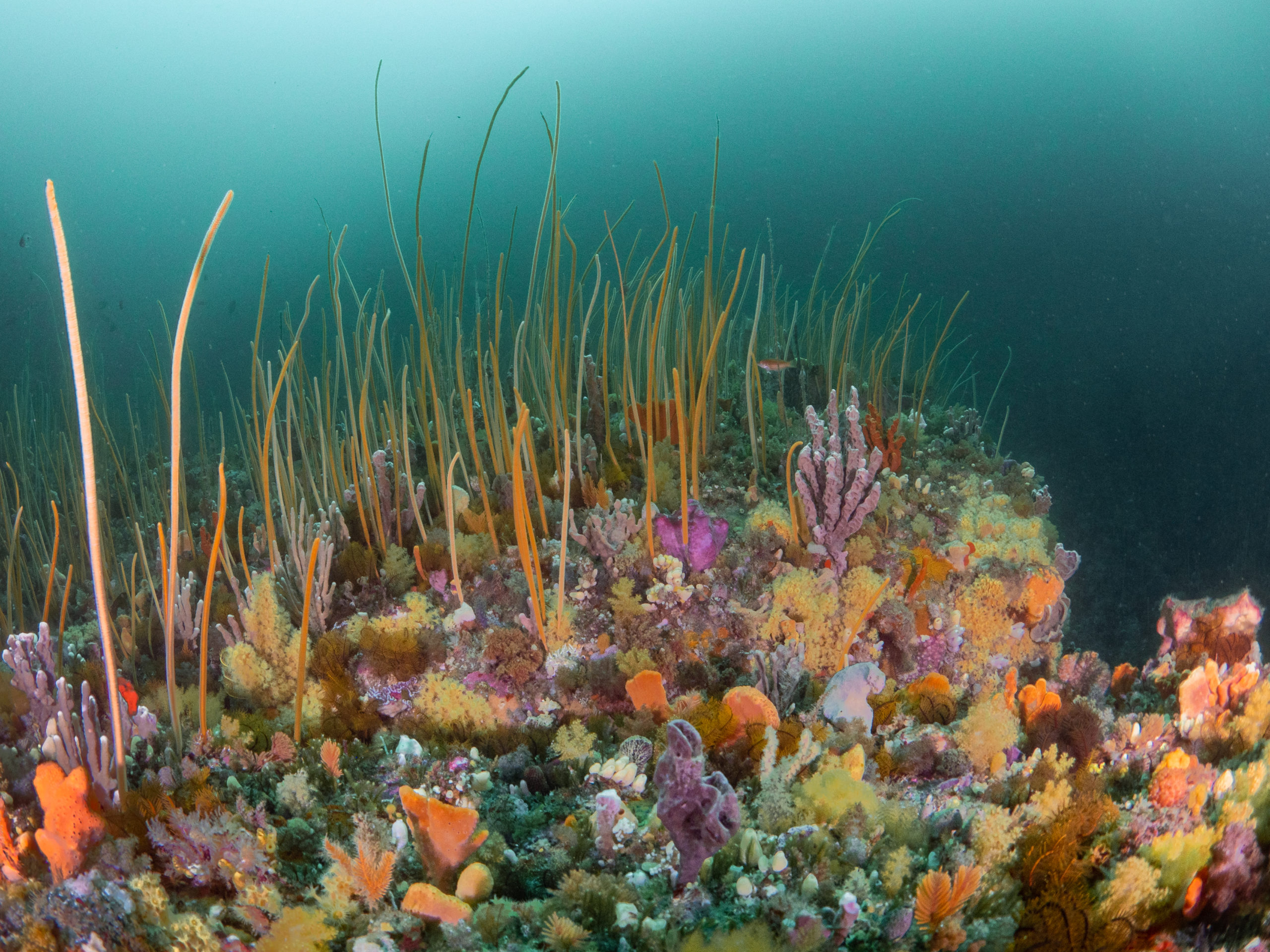

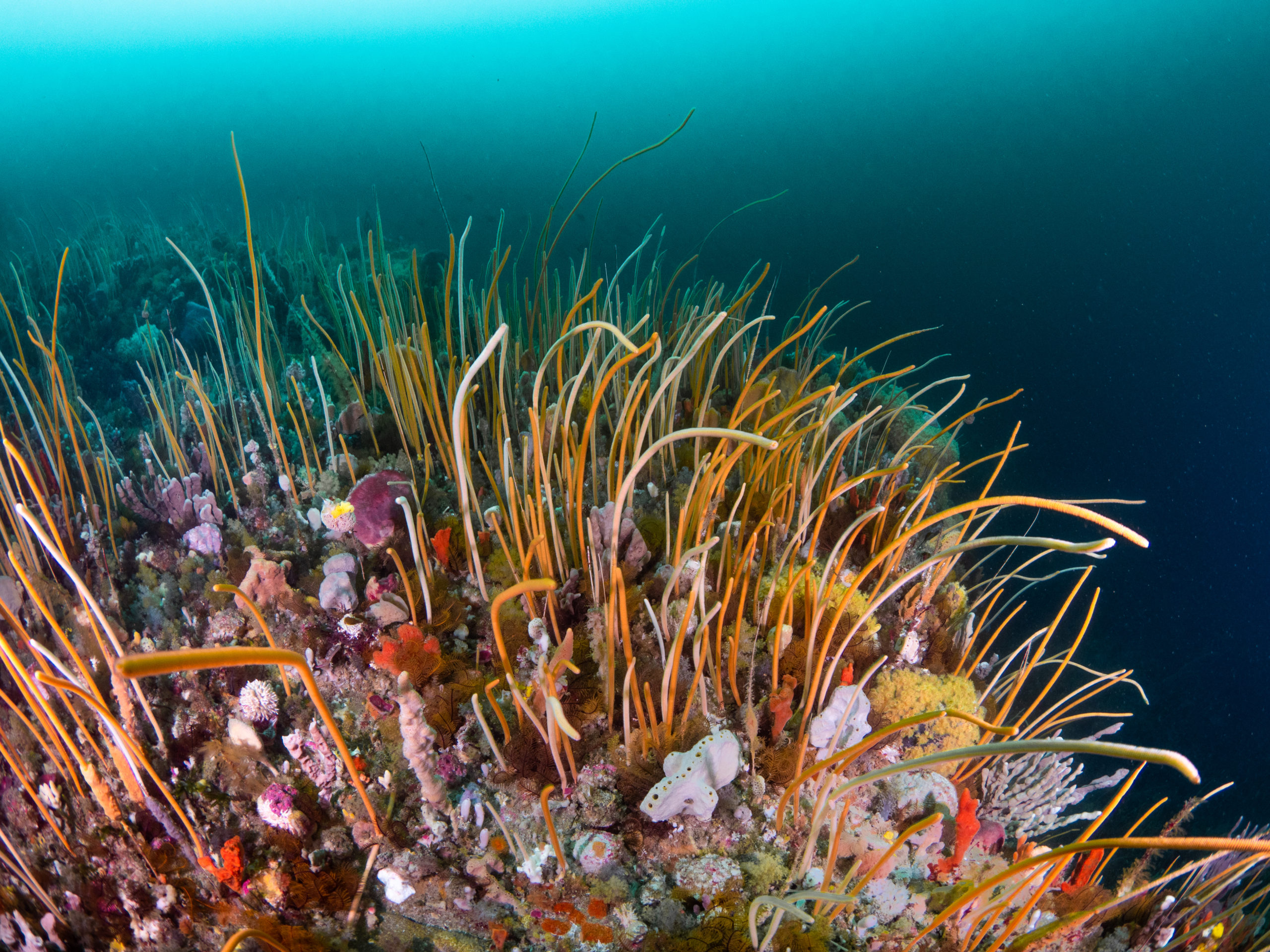

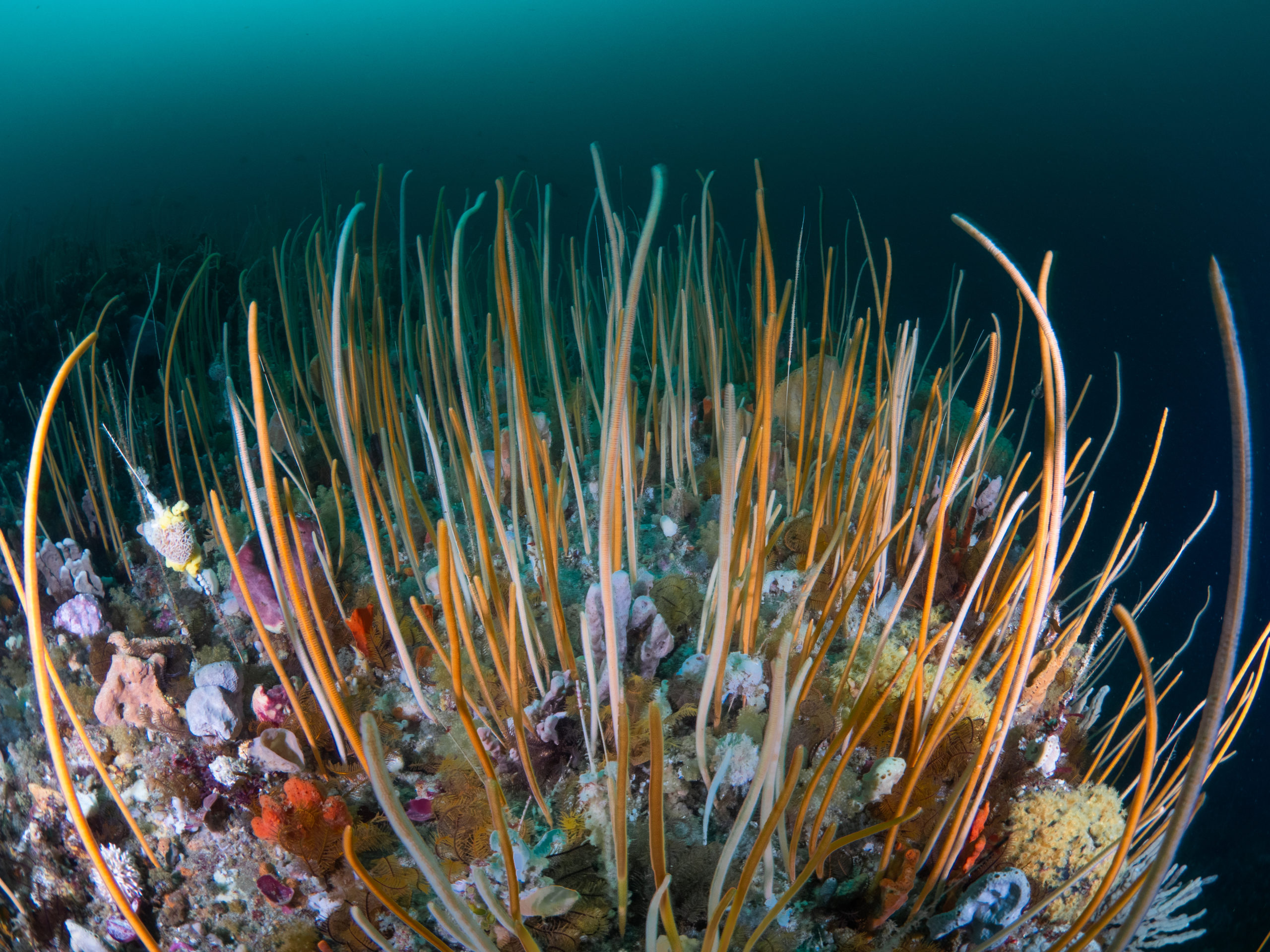

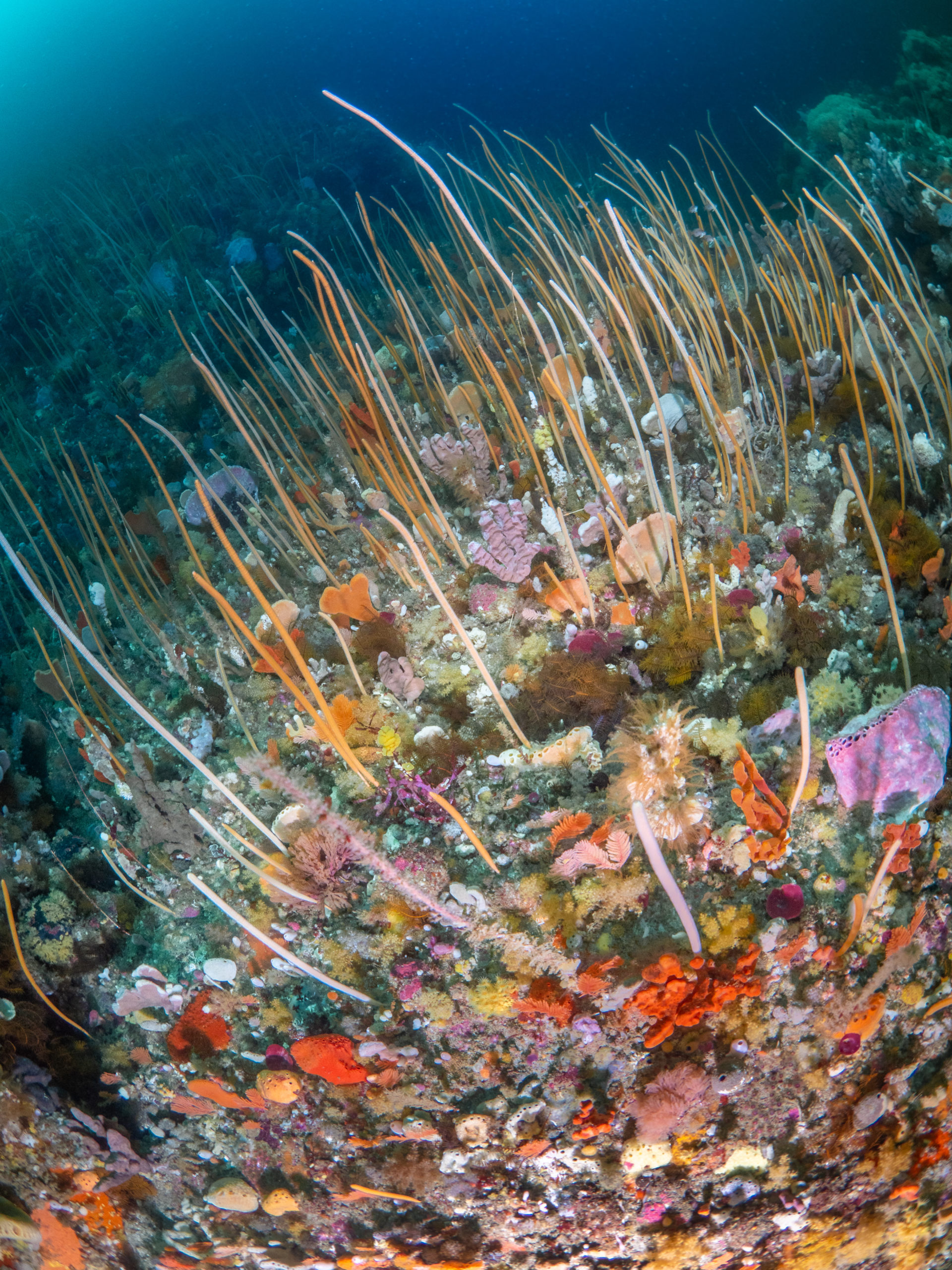

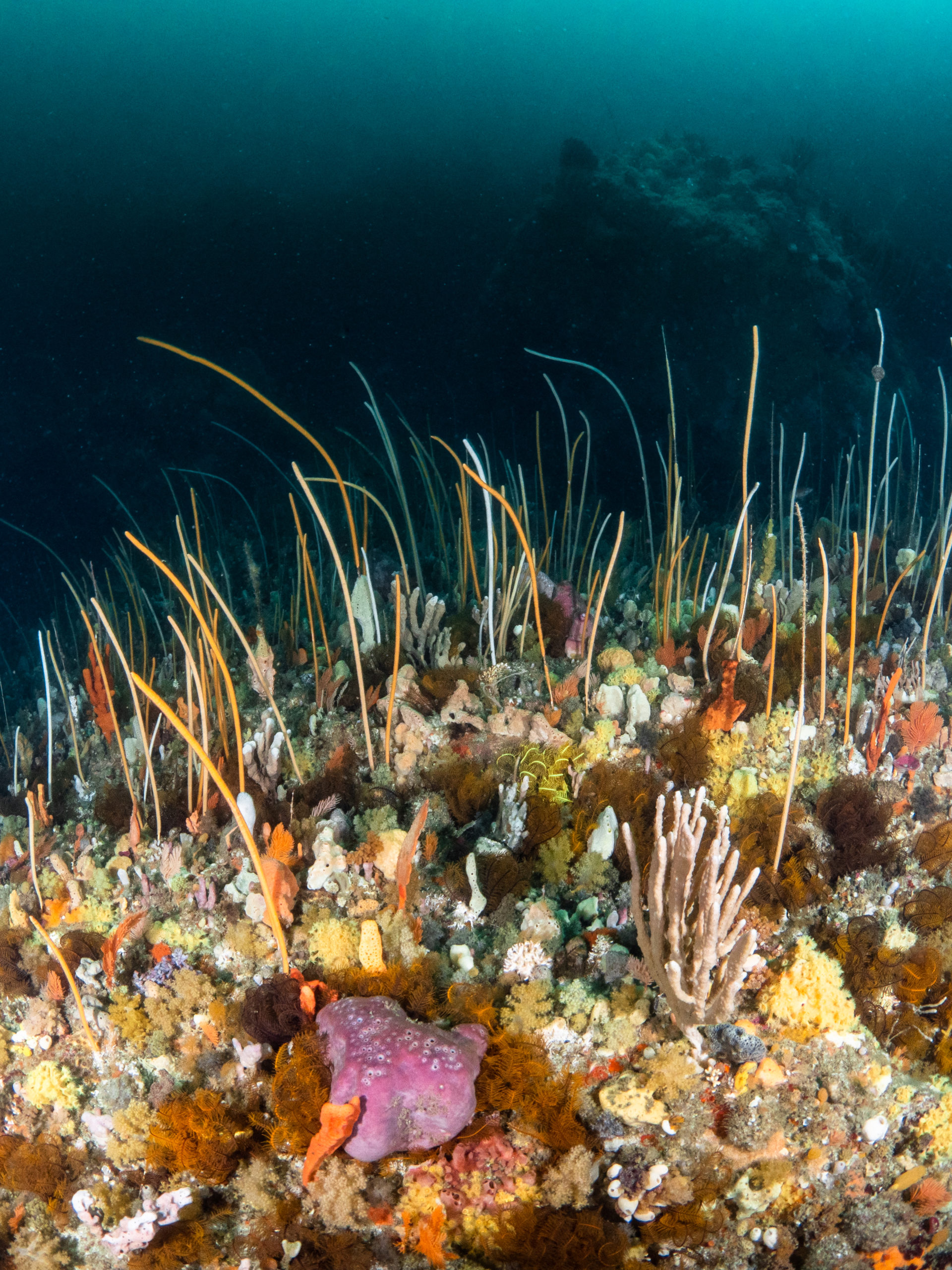

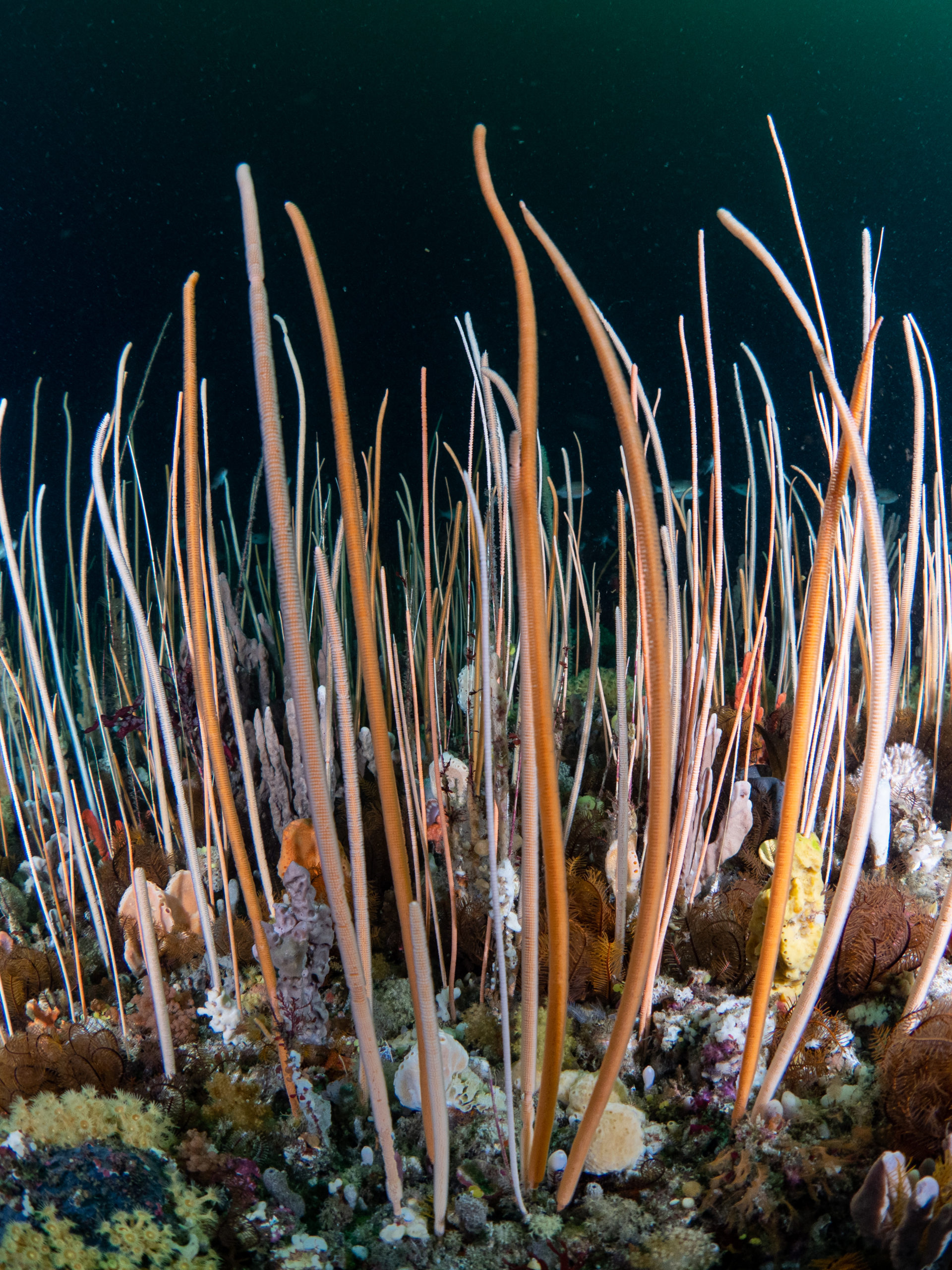

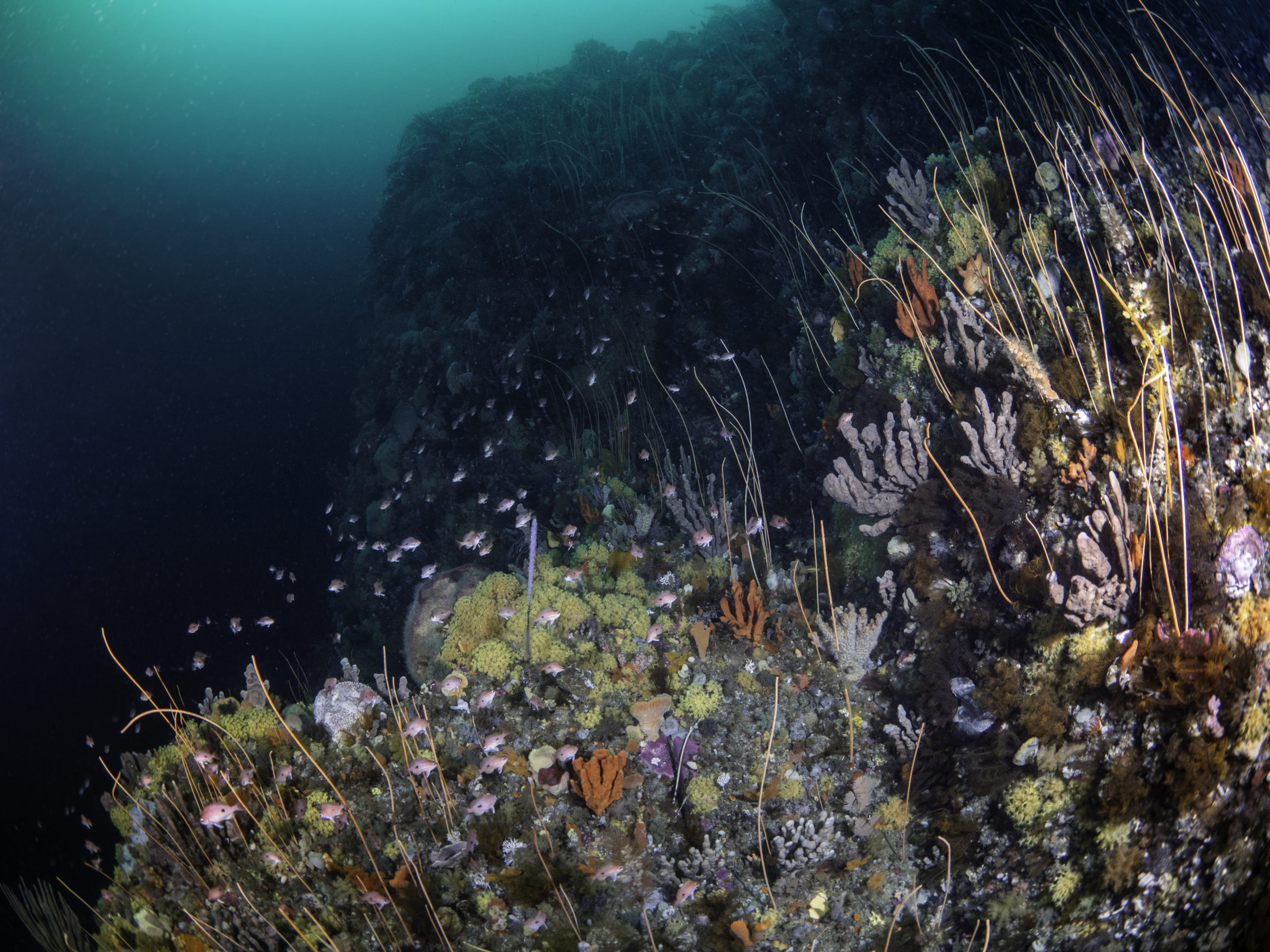

“Sea whip corals, each about half a metre high, blanket the rocks. When you first spot them, it looks like colourful hairy boulders.

“Then, up close, in amongst all the whip corals, you’ve got a multitude of different sponges – every colour you can imagine.

“So you’ll be swimming along these boulders, you’ll turn and see a sheer cliff wall, and that’s where you’ll find the yellow zoanthids. They’re these amazing vibrant yellow tiny coral polyps that blanket any vertical surface.

“It’s better than the Great Barrier Reef.”

These are the words of Matt Testoni, underwater photographer, professional diver and marine biologist.

He’s describing a collection of coral reefs, located off the south east and south coasts of Tasmania.

While they’ve been known to scientists and others in Tasmania’’s marine community for more than 50 years, these underwater treasures remain relatively unknown to most Australians.

“It’s such an understudied and undervisited area,” says Matt.

“The corals start at about 30–35 metres, and continue down until the seafloor,” he explains. “And it’s not the easiest section of coast to dive.”

This makes them not as accessible as other coral reefs around the country.

And, unlike other better-known reefs, including our most famous Great Barrier Reef, which are made up of hard corals, the species that form Tasmania’s coral reefs are the soft variety.

But, just like hard coral ecosystems, these soft coral communities also play a vital role in supporting local marine life.

“The most common species you’ll see here are the black-spotted butterfly perch, large schools of them,” says Matt.

Unfortunately, these southern reefs are not immune from the effects of climate change threatening so many of Australia’s natural environments.

“Global warming has made the East Australian Current (EAC) extend from Victoria down the Tassie east coast and that extension has brought warmer waters with it, it’s also brought tropical waters that are a lot more nutrient deficient,” explains Matt.

The extension of the EAC has also allowed the long-spined sea urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersii) to move south into Tasmanian waters where it previously could not survive the cooler temperatures.

“They eat absolutely everything,” says Matt.

“They create what they call ‘urchin barrens’ that look like underwater deserts, it’s quite sad.”

Thankfully, in part to the extensive efforts of the Tasmanian Government to curb their spread, the urchins haven’t reached the corals in mass numbers.

“The government is spending a lot of money cleaning them up, which is helping,” says Matt.

“But I do see the occasional one of these invasive urchins on the reefs.”