Echidnas blow snot bubbles to stay cool

Echidnas. They love to swim, their hind feet point backwards, they lay their eggs into a pseudo-pouch, they can enter a temporary hibernation-like state to conserve energy, they can dig vertically, the hatchlings respire through their skin, and the males even have a four-pronged penis.

And now, another peculiar trait has been discovered.

For a long time, we have known echidnas can’t sweat, pant, or lick – actions other animals perform to keep their bodies cool.

Yet these monotremes have impressive thermal tolerance. How they do it has perplexed the scientific community for years.

Now, we finally know the answer. It turns out they stay cool by blowing mucus bubbles through their beak.

It’s not glamorous but it works.

Dr Christine Cooper from Curtin University’s School of Molecular and Life Sciences explains:

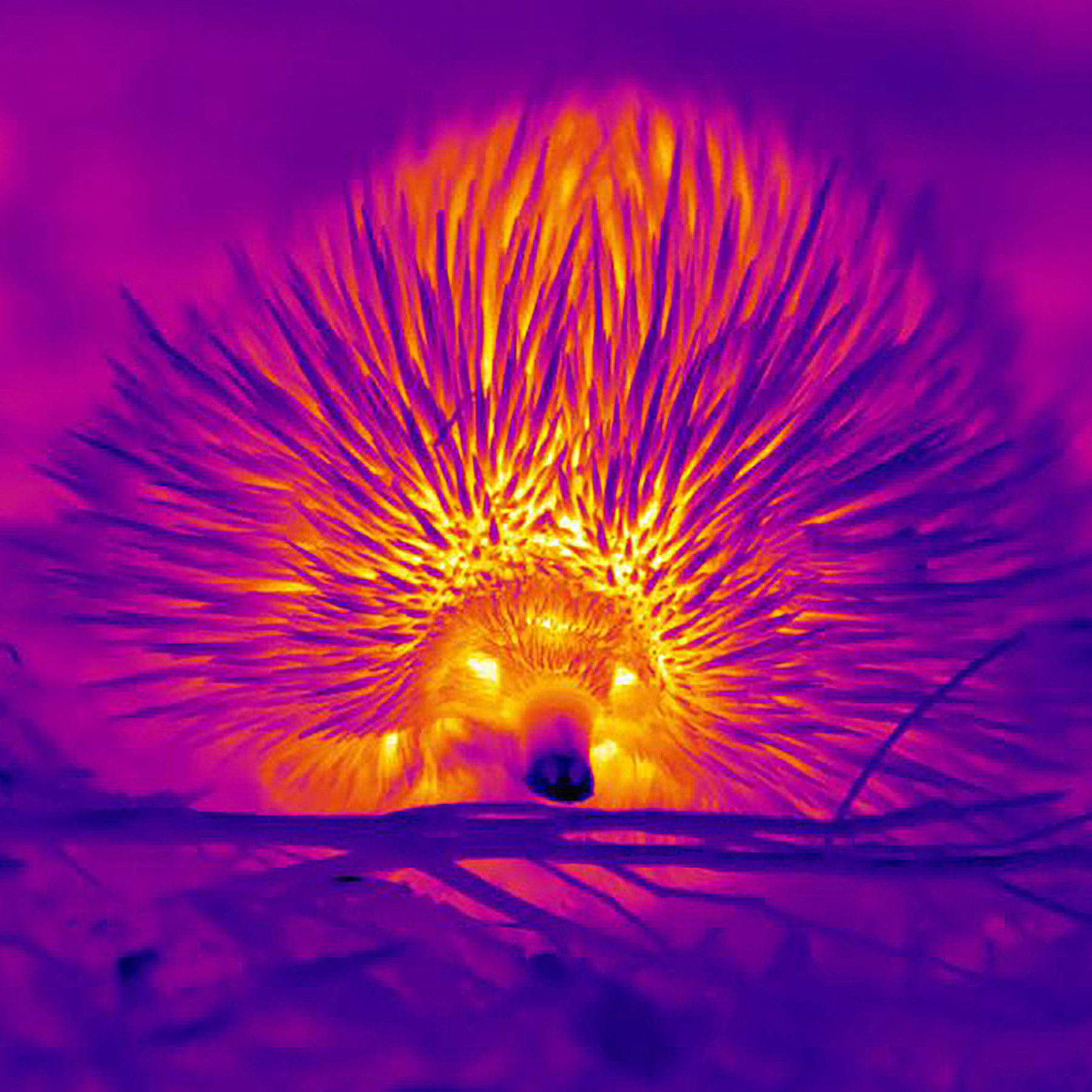

“Echidnas blow bubbles from their nose, which burst over the nose tip and wet it. As the moisture evaporates it cools their blood, meaning their nose tip works as an evaporative window.”

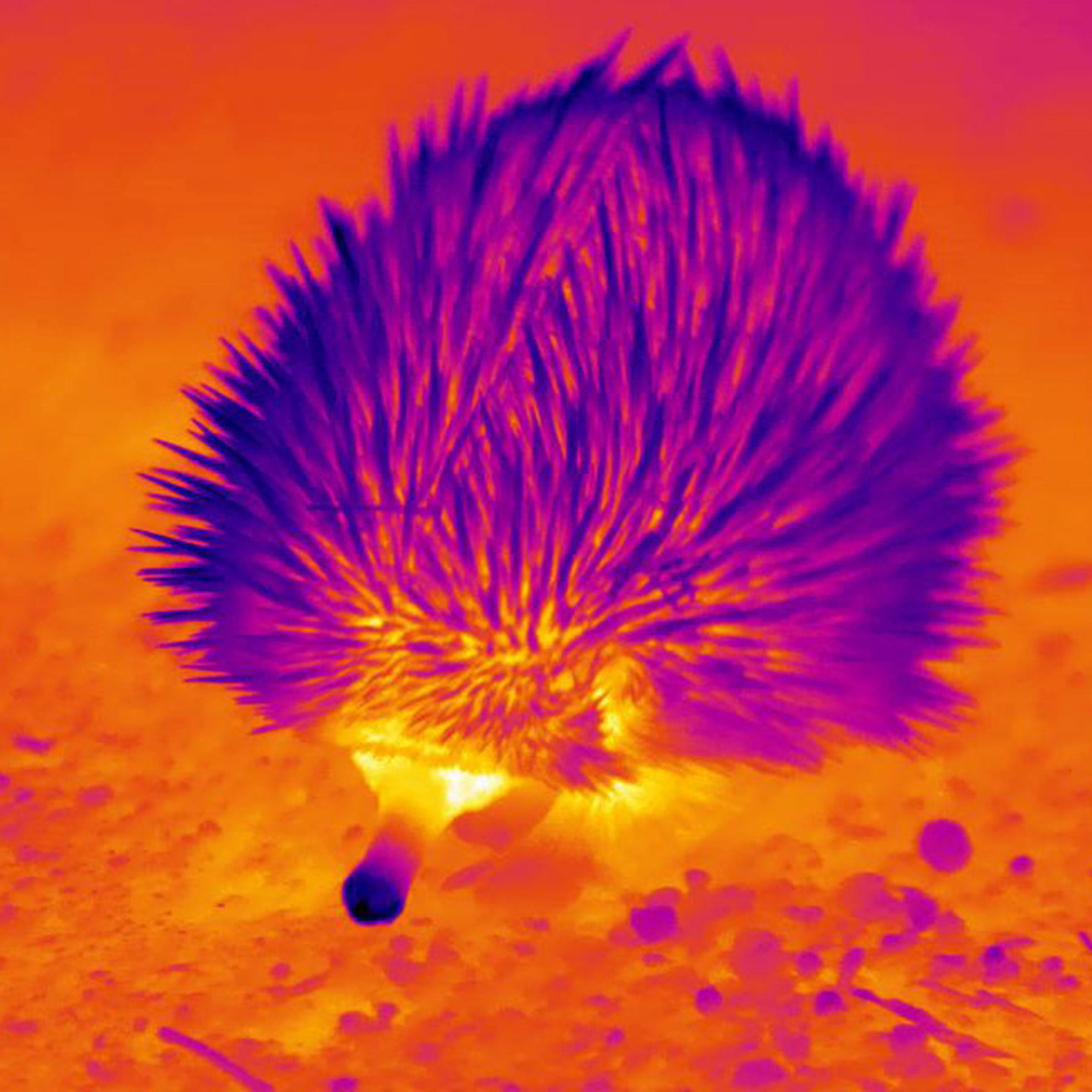

This behaviour was discovered using thermal imaging cameras.

A group of wild short-beaked echidnas were filmed in a patch of bushland about 170km southwest of Perth.

The footage was then studied to show how the animals exchanged heat with their environment.

And it doesn’t stop at snot. Echidnas have other cooling techniques too, allowing them to be active at much higher temperatures than previously thought, says Dr Cooper.

“We also found their spines provide flexible insulation to retain body heat, and they can lose heat from the spineless areas on their underside and legs, meaning these areas work as thermal windows that allow heat exchange.”

Dr Cooper adds that understanding the thermal biology of echidnas is also important in predicting how they might respond to climate change and a warming environment.

These findings have been published in Biology Letters, titled ‘Postural, pilo-erective and evaporative thermal windows of the short-beaked echidna’.

The research was funded by an Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery grant.