Scientists begin studying bodies of whales from recent WA mass stranding

Fifty-two of the long-finned pilot whales died initially during the mass stranding. Wildlife experts and volunteers spent the next two days trying to escort the remaining 45 whales out to sea, but after repeatedly returning to the beach, the difficult decision was made to euthanise the distressed mammals.

Unfortunately, mass stranding events are common for pilot whales – both the long-finned (Globicephala melaena) and short-finned (Globicephala macrorhynchus) species. While scientists have many theories, no one really knows exactly why they do it.

But this latest stranding presented scientists with some possible clues.

For the first time, the behaviour of the pilot whales in the time leading up to their stranding was witnessed, and captured by drone cameras.

The animals were seen huddling together in a tight group and swimming very close to shore.

“The fact they were in one area, very huddled and doing really interesting behaviours and looking around at times suggests something else is going on that we just don’t know,” said Macquarie University wildlife scientist Vanessa Pirotta at the time.

Experts speculated the whales could have been ill, or suffering stress caused by loud underwater noise.

Now, these theories are being tested.

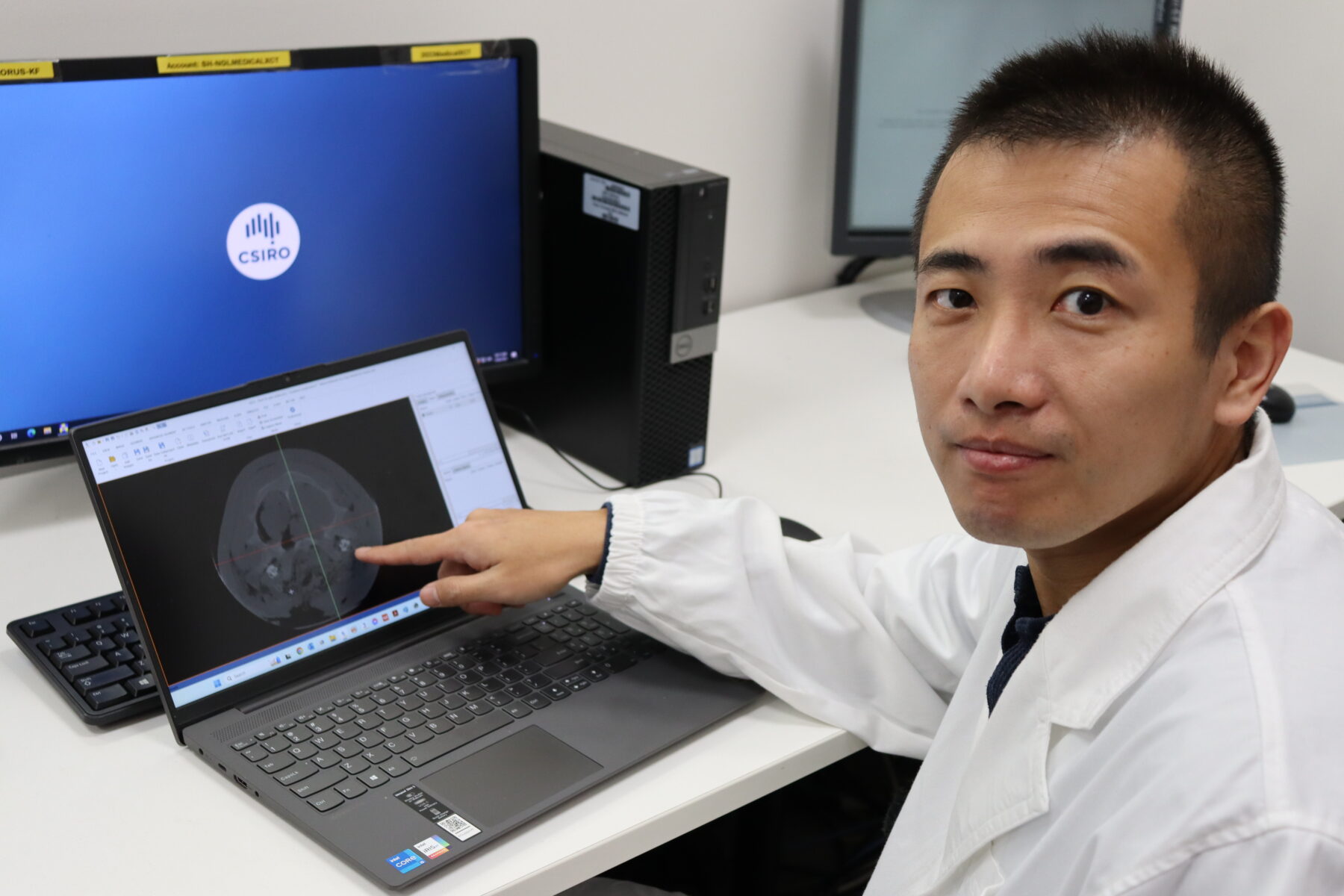

Marine scientists at Perth’s Curtin University are using micro CT scanning technology to assess the inner ears of three of the deceased whales.

These CT scan images will be compared to existing CT scan data from the ears of healthy pilot whales to look for any damage to the hearing or echolocation structures.

But first, the team will scan the entire bodies of the whales to rule out illness or injury as causes for the stranding.

“We have received three of the whales that died in the stranding, of differing sexes and ages,” explains Dr Chong Wei, a marine bioacoustic specialist at Curtin’s Centre for Marine Science and Technology.

“First, we will scan the whole of the pilot whales and check for any significant sicknesses or injuries to the internal bodies of the animals… because medical CT scans can check the whole body, but micro CT scans provides a much higher resolution.”

The focus will then move to the ears.

“Then we will do the dissection and do a micro CT scan of the ears to see if there is damage,” says Dr Wei.

“If we find any evidence of ear damage we will be able to assess how this damage was caused.

“Sometimes, when an animal is exposed to a very intense sound [either once or over a period of time] that can cause some damage.”

Dr Wei has previously researched the effects of seismic testing on the ears of fish.

‘We’ve done some research before In our lab about how seismic survey signals cause damage to fish ears and we found if a seismic survey uses very high intensity pulses and fish ears are exposed to this high intensity sound for a period of time, we found small holes and blisterings in the membrane of the ears, so we want to know if this has a similar effect on whales.”

“These are vital clues that may indicate whether some form of inner-ear damage played a role in the devastating mass stranding of the whales on WA’s south coast.”

3D acoustic models of the deceased whale’s ears will then be created using the information from the micro CT scans.

“We can build acoustic models that simulate sound production, as well as the propagation and reception processes that occur inside the animal’s head,” explains Dr Wei.

“In particular, we want to know if there could be interference to the whales’ echolocation system.

“Pilot whales are toothed whales, and toothed whales rely heavily on their echolocation – for navigation, pretty much for everything.

“So we want to see if [interference with their echolocation systems] could have potentially caused them to lose their sense of direction or anything else that caused the stranding.”

Dr Wei says he expects to be able to share some results from the research within several months.