How the Great Barrier Reef shows record growth AND intense bleaching

It was another difficult summer on the Great Barrier Reef. A serious marine heatwave caused the fifth mass coral bleaching event since 2016. Intense rain from Cyclone Jasper washed huge volumes of freshwater and sediment onto corals closer to shore, and Cyclone Kirrily crossed the central region. Some parts of the southern reef endured heat stress at levels higher than previously measured.

Has this summer’s bleaching killed many corals on the Barrier Reef – or will they recover? The answer is – we don’t know yet. The latest Australian Institute of Marine Science coral cover report, released today, reports coral cover has increased slightly in all three regions, reaching regional high points in two of them.

How can that be? The answer is simple: lag time. Between 2018 and 2022, large areas of the Great Barrier Reef had a reprieve. Marine heatwaves and bleaching still occurred, but the damage was not too extreme. Coral began to recover and regrow.

Over the 2023–24 summer, the heat returned with a vengeance, triggering widespread coral bleaching. But bleached coral isn’t dead yet – it’s very stressed. The summer’s bleaching is only just winding up now, in August. We won’t know how much coral actually died until we complete our next round of surveys. We’ll be back in the water from September to find out.

How can we reconcile high coral cover and intense shocks?

Bleached coral is very stressed, but it’s still alive.

Corals respond to intense heat by expelling their tiny symbiotic algae, or zooxanthellae. In the process, they lose their colours and become bone-white. If the heat eases, the zooxanthellae can sometimes return, and the corals can bounce back.

But if temperatures stay high, corals die. A dead coral is not bone-white – it’s covered in light green fuzz, a sign of colonisation by filamentous algae.

What this means is it takes time to say a coral is truly dead.

For almost four decades, AIMS scientists have monitored the Great Barrier Reef. It’s no easy task to monitor a reef system the size of Italy.

To do it, our team spends 120 days at sea between September and June, across six separate trips.

The two trips we did during the peak of the mass bleaching event in February and March recorded bleached coral as live coral cover – because they were alive when we did the surveys.

So while our new report provides an update on the state of the reef, we cannot use it to describe the full impacts of this summer’s bleaching. It’s a reference point.

Surveys found the average hard coral cover in the year to June 2024 was:

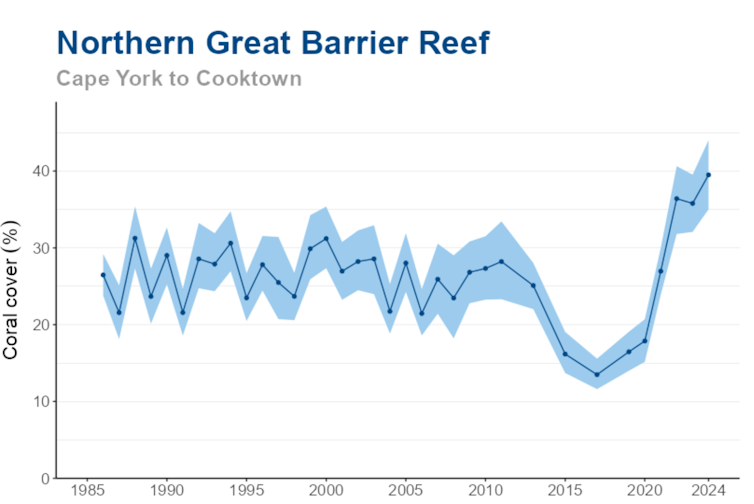

- 39.5 per cent in the northern region (north of Cooktown), up from 35.8 per cent last year.

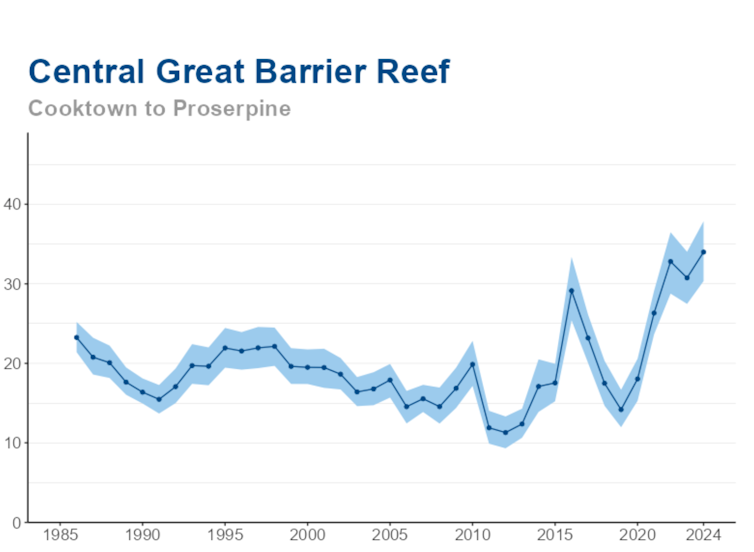

- 34 per cent in the central region (Cooktown to Proserpine), up from 30.7 per cent.

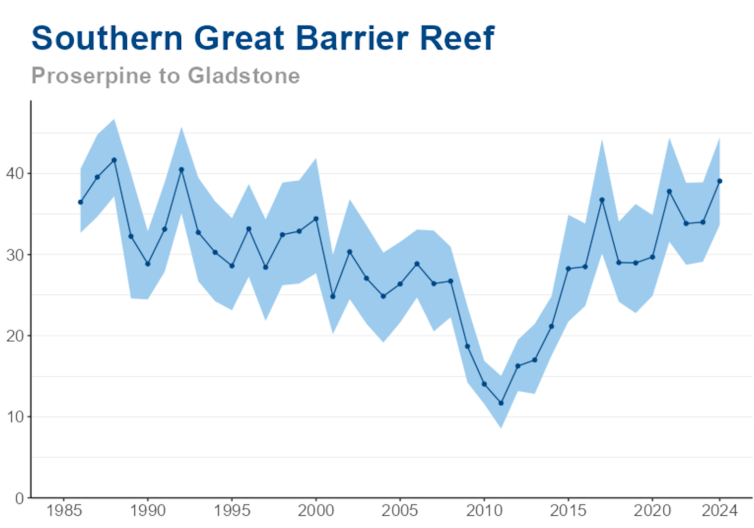

- 39.1 per cent in the southern region (south of Proserpine), up from 34 per cent.

This year’s coral cover averages are higher than the last few years, but not by much. Statistically speaking, they’re within the margin of error.

By contrast, the reef recovered much more strongly during the less stressful years from 2018 to 2022. In the northern region, coral cover increased by 22.9 per cent.

If we were living in ordinary times, corals would grow back over a decade or two, giving rise to more diverse reefs.

But as the world heats up, the reprieve from heatwaves and extreme weather is getting shorter and shorter. In recent decades, both size and frequency of events causing severe damage to the reef have increased.

How bad was this year’s bleaching?

This year’s marine heatwaves peaked in February and March, when researchers from AIMS and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority conducted additional surveys from the air and underwater.

What this showed was the 2024 mass bleaching event was one of the most serious and widespread so far. It took place against the fourth recorded global bleaching event.

Heat stress is cumulative – it gets worse the longer corals have to endure warmer water.

Some of the southern reefs were exposed to up to 15 degree heating weeks, a measure of the accumulated heat stress. Such high levels have never been recorded on the reef before.

Our aerial surveys detected extreme levels of bleaching – affecting over 90 per cent of corals on a reef – across all three regions of the reef, though not equally. Extreme bleaching was widespread in the southern region of the reef, but less so in the northern and central regions.

Reports of coral death on bleached reefs are beginning to arrive, but it’s too early to draw broad conclusions about the full impact of this event.

What will happen next?

During the cooler months, bleached corals can recover, but it’s not guaranteed. Bleaching makes it harder for corals to grow and reproduce, and leaves them more susceptible to disease. If their symbiotic algae return, some corals will recover, but many corals will not make it. We won’t know the death toll until after we do our next roundDaniela Ceccarelli, David Wachenfeld and Mike Emslie of surveys.

While coral cover has increased and decreased over time, the variability has become much more erratic. Over the last 15 years, coral cover has had its highest highs and lowest lows on record.

What we should take from this is the reef – the world’s largest living structure – is currently still able to recover from repeated shocks. But these shocks are getting worse and arriving more often, and future recovery is not guaranteed.

This is the rollercoaster ride the reef faces at just 1.1°C of warming. The pattern of disturbance and recovery is shifting – and not in the Reef’s favour. ![]()

Daniela Ceccarelli is a Reef Fish Ecologist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science.

David Wachenfeld is the Research Program Director of Reef Ecology and Monitoring at the Australian Institute of Marine Science.

Mike Emslie is a Senior Research Scientist in Reef Ecology at the Australian Institute of Marine Science.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.