Troubled waters: Australia’s freshwater fish are facing extinction

Three-quarters of Australia’s freshwater fish species are found nowhere else on the planet. This makes us the sole custodians of remarkable creatures such as the ornate rainbowfish, the ancient Australian lungfish and the magnificently named longnose sooty grunter.

So how are these national treasures faring? To find out, researchers undertook the first comprehensive assessment of Australia’s freshwater fish species, examining extinction risks and drivers of decline, before reviewing existing conservation measures.

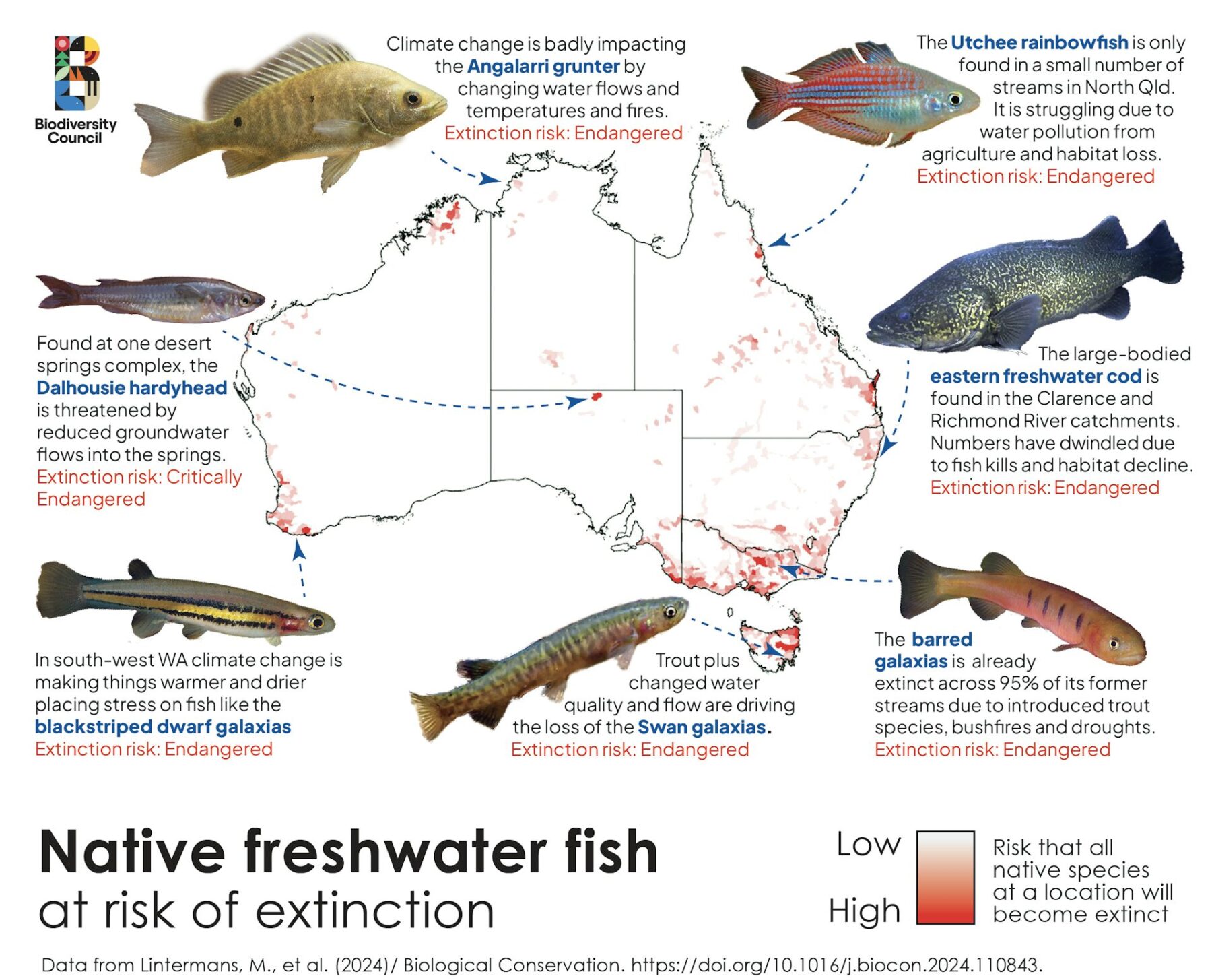

The results paint an alarming picture. More than one-third (37 per cent) of freshwater fish species are at risk of extinction, including 35 species not even listed as threatened. Dozens of species could become extinct before children born today even finish high school.

The study also reveals Australia has been putting its eggs in the wrong basket for conservation by taking actions that don’t address immediate threats, such as pest species and changes in stream flows. This research points to more effective solutions if governments are willing to improve their efforts.

Identifying species at risk

Recognising when species are in trouble is the first step in preventing their extinction.

Before this study, the extinction risk of most freshwater fish species had never been assessed. The group had never been looked at overall.

Researchers evaluated the conservation risks of 241 species using globally recognised criteria (the IUCN Red List for Threatened Species).

They began their assessments by gathering a team of 52 Australian freshwater fish experts for a five-day workshop in 2019. These experts came from universities, research organisations, museums, state government agencies, natural resource management, consultancies and non-government groups.

Together, information from scientific publications, museum databases, Atlas of Living Australia records, government datasets, citizen science data and the researchers’ own knowledge of freshwater fish as it applied to the task was used.

The study identified dozens of freshwater fish species that were in trouble but had not been recognised as threatened. This brings the proportion of our freshwater fishes at risk of extinction to a third.

Some species have declined to the extent that they could disappear after a single disturbance, such as ash washed into streams after a bushfire or the arrival of an invasive non-native fish such as trout.

The research also found one New South Wales species, the Kangaroo River perch, is now extinct.

Get them on the list

At present, 63 freshwater fish species are on Australia’s national list of species declared as threatened under federal environmental law.

The study identified 35 more species that should be listed, based on the available evidence. They include:

- ornate rainbowfish and longnosed sooty grunter (vulnerable on the IUCN Red List, the global list of threatened species)

- salamanderfish (endangered on the IUCN Red List)

- the slender carp, Drysdale and Barrow cave gudgeons in Western Australia (critically endangered on the IUCN Red List).

Maintaining an accurate threatened species list is important. When species are in trouble but not listed, they miss out on basic protections and are unlikely to receive any conservation attention.

Researchers also identified 17 already listed species that should be reassessed by the government as their risk categories need to be changed.

For example, the remarkable freshwater sawfish, found in northern Australian rivers, is listed as vulnerable but all evidence indicates it’s now critically endangered.

One sliver of good news is the fact that the Murray cod, a favoured sport fish across eastern Australia, is now doing better and could be assessed to be removed from Australia’s threatened species list.

Address the causes of decline

To prevent species extinctions, the causes of their declines must be addressed. That might seem breathtakingly obvious, yet this review found a spectacular mismatch between the major threats to species at risk and the most common conservation actions.

The top three drivers of decline are invasive fish (which threaten 92 per cent of threatened freshwater fish species), modified stream flows and ecosystems (82 per cent), and climate change and extreme weather (54 per cent).

For example, Australia has 40 galaxiid species, scaleless native fish shaped like slender sausages that grow to less than 15cm. But 31 of these are threatened with extinction – and rainbow and brown trout, two introduced predators, have been the biggest driver of their loss.

Australia’s southern states are greatly adding to the problem by releasing millions of trout into waterways each year for recreational fishers.

The endangered eastern freshwater cod has dwindled in part due to historic fish kills linked to dynamite blasting and pollution from mines and agriculture. It remains threatened by changes to river flows, removal of woody snags, and other damage to its habitat.

The endangered blackstriped dwarf galaxias is being stressed by the changing climate in southwest WA. Warmer and drier conditions are resulting in lower water levels and warmer water.

The other major threats facing native fish are agriculture and aquaculture (38 per cent), pollution (38 per cent), hunting and fishing (19 per cent), energy production and mining (17 per cent) and urban development (13 per cent).

For example, the endangered Utchee rainbowfish is struggling due to habitat loss and water pollution from farms surrounding the small number of north Queensland streams where it lives.

In contrast, the most common conservation action was simply the fact that the species occurred in a protected area (88 per cent) or conservation area (55 per cent).

Sadly, invasive species and climate change don’t recognise or stop at protected area boundaries.

Prevention and control of invasive species has occurred for only 21 per cent of affected threatened species, mostly in Tasmania.

A blueprint to end extinctions

Without a major funding commitment to address the actual drivers of native fish losses, species will continue to decline, and extinctions will soon follow.

The most important conservation actions for native freshwater fish are:

update the national threatened species list to include all at-risk species

tackle invasive species such as trout, gambusia and redfin perch

identify, establish and protect additional invasive-fish-free refuge sites for species that currently occur only in a small number of locations and could be wiped out by a single event such as a bushfire

halt ongoing habitat loss and improve habitats that have been damaged

improve freshwater flows to maintain habitats such as wetlands and streams, improve water quality and give fish the natural cues they need to breed.

In 2022, the Australian government made a commitment to end extinctions. This study provides a blueprint for how to do that for our overlooked native freshwater fish. ![]()

Mark Lintermans is an adjunct associate in freshwater fisheries ecology and management at the University of Canberra.

Jaana Dielenberg is a university fellow in biodiversity at Charles Darwin University.

Nick Whiterod is a science program manager for the Goyder Institute for Water Research CLLMM Research Centre at the University of Adelaide.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.