Ever heard of a chuditch? Judging by the species’ huge natural range, which includes every mainland state and territory, it should be as familiar to most Australians as the emu or koala. But unless you live near Perth in Western Australia, you’re unlikely to have ever heard of this charismatic little spotted marsupial.

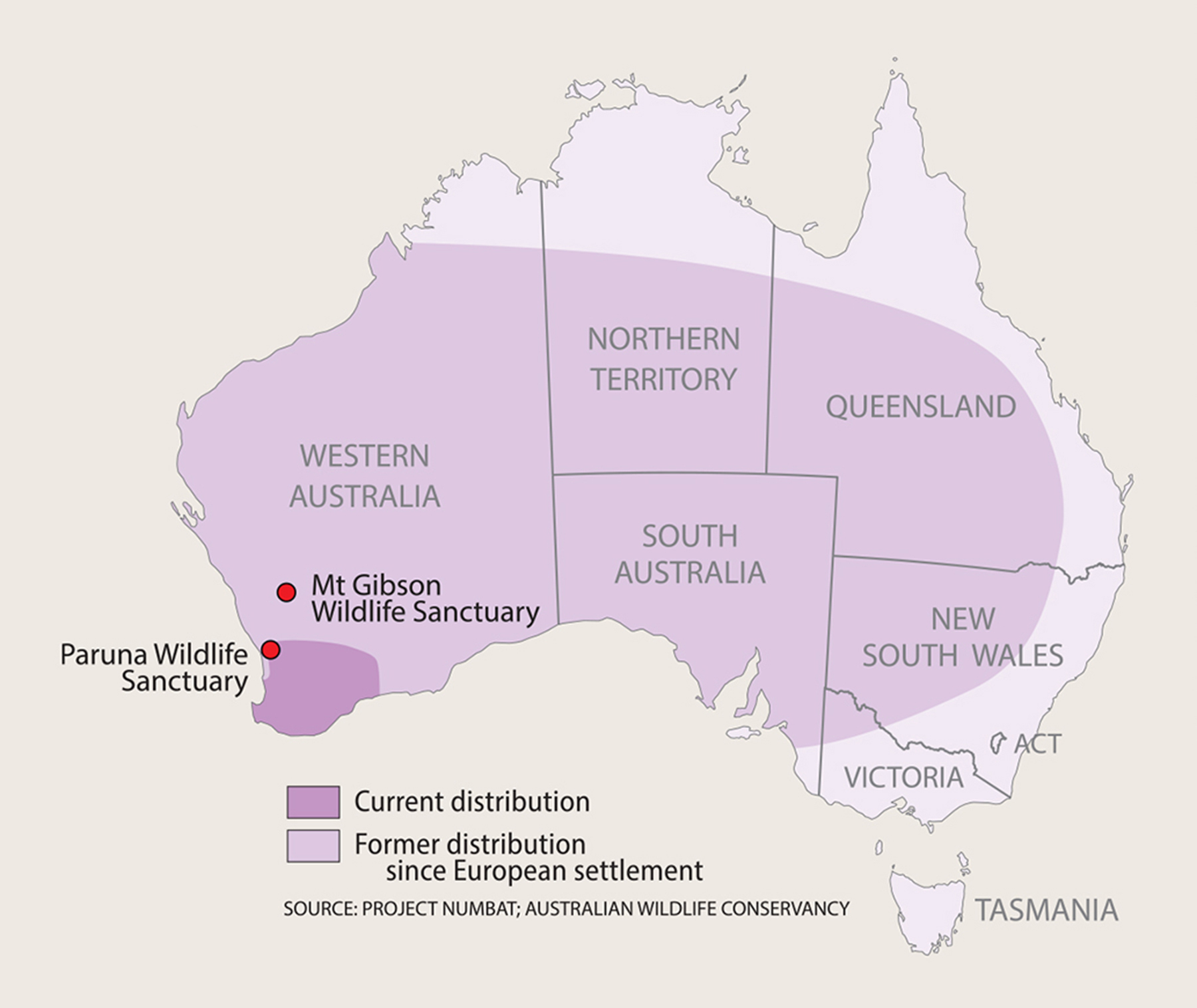

The chuditch (Dasyurus geoffroii)– also know as the western quoll – is another of those small-to-medium-sized mammals that only occurs in Australia, but has been almost completely wiped out during the past 200 years. Their natural distribution has been reduced by more than 90 per cent since European settlement and its last remaining natural strongholds are a handful of isolated populations south of Perth.

A few limited translocations earlier this century saw the chuditch reintroduced to South Australia, although it remains endangered there. And the species continues to be either extinct or presumed extinct in the Northern Territory, New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria.

After a decade of planning, in 2023 Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC) carried out the first of five planned translocations to Mt Gibson Wildlife Sanctuary, 350km north-east of Perth, of animals caught from remnant wild chuditch populations near Perth. It was the start of an ambitious plan that might one day lead to the species being re-established across much of its former range.

‘A huge program’

Mammal reintroductions have been a key feature of management for the Mt Gibson sanctuary and crucial to this has been the property’s large predator-free enclosure. Almost 8000ha of the property’s most intact habitat has been protected within a 43km x 1.82m specially designed feral-proof fence.

In 2015 AWC began reintroducing to the property 10 mammal species that had been extinct in the area for many years, including nine species that are also threatened at the national level. It started with the greater bilby in 2016, and has since seen populations of numbat, woylie, Shark Bay bandicoot, red-tailed phascogale, greater stick-nest rat, banded hare-wallaby and the WA subspecies of the brushtail possum become established within the safety of Mt Gibson’s feral predator–free enclosure.

“It’s been a huge program. But it’s been worth it,” says Isabel ‘Issie’ Connell, a field ecologist and senior guide at the Mt Gibson sanctuary. “This is the first place in the world to reintroduce so many species into one area.”

Not only have these reintroduced populations begun to flourish safely away from the foxes and cats that have decimated their numbers, but the environment has also begun to visibly respond positively to the presence of the animals.

“Something that many people may not be aware of is how important these animals are in the ecosystem and in the landscape,” Issie says. She points out that, as a result, the condition of the soil inside the fence is remarkably better than it is outside. “That’s because of the work done by the animals we’ve reintroduced there,” she says.

The extensive scratching and digging – while looking for food and making burrows – by the mammal species so far introduced behind the fence turns over huge quantities of soil every day. “The reason this is so important,” Issie says, “is that every time a little dig is done, it’s breaking up the topsoil and pulling down nutrients. When it rains the water doesn’t just run off, it actually penetrates the ground, and this can really have quite a quick effect on the quality of the habitat.”

The return of the chuditch to Mt Gibson began in 2023 with the same sort of intensive planning that had been undertaken for the other species, but with one important difference: The other mammals are mostly herbivorous, but the chuditch is a carnivore that eats large invertebrates, reptiles and small mammals. For now it has been decided to establish the translocated chuditch populations outside the predator-proof fence, to give the protected herbivores within more time to become established before being exposed to another native predator. (Natural populations of goannas, snakes and birds of prey all presently hunt for food behind the fence.)

The other issue facing chuditch is that, being a carnivore, the species requires a much larger home range than other herbivores – a male chuditch can range across at least 1500ha and females need up to 400ha for hunting prey and searching for mates.

As a result, an intensive effort went into making a huge area outside the fence as free of feral predators as possible for the chuditch translocations. “To be able to release outside the fence, we had to get cats and foxes down to a reasonable level,” says Georgie Anderson, who was until recently the senior field ecologist at Mt Gibson. Foxes are now rarely seen on the sanctuary or the surrounding area, but feral cats are an ongoing problem.

“Cats are a big thing for us and incredibly difficult to manage, because different approaches work for different cats,” Georgie says. “So we do a whole suite of different controls.” Feral cat suppression is an ongoing part of management right across the property, and it was stepped up about 18 months before the first chuditch translocation, in the area where they were being released.

“Across Mt Gibson we trap for cats. We also aerial- and ground-bait with Eradicat® [a commercial product that uses 1080 poison]. But we’ve also been trialling the Felixer grooming trap for the past year.” A Felixer is a device that uses a camera-based artificial intelligence system to attract feral cats, recognise them and spray them with 1080, which they then ingest when they groom.

Breeding underway

The fifth and final translocation of wild chuditch went ahead at Mt Gibson in May 2024, releasing 18 animals caught at Dryandra Woodland National Park, 180km south-east of Perth. In the 12 months prior to the release, more than 20 feral cats were removed from the area using a combination of Felixers and traps. As with the other releases, a mix of male and female chuditch were chosen and released at selected locations outside the fence, after first resting up for vet checks and a good feed at Perth’s Chuditch Hotel, a purpose-built facility operated by Native Animal Rescue.

Some of the released animals were fitted with radio-tracking collars, and data from these revealed some animals dispersed far and wide shortly after release, even as far as neighbouring properties. These data, along with field sightings, trapping of the translocated animals and evidence from camera traps, demonstrated that the program overall has so far been successful in establishing a chuditch population back at Mt Gibson.

“We’ve shown that we’ve got really high survivorship, with a couple of mortalities from predation. But some of those predation events have been by native animals, including by a bird of prey,” Georgie says. “There were a couple of mortalities that were likely to be cat or fox. But it was low enough that we think the majority are doing okay.”

Perhaps, however, the best indicators of the population’s health are signs of breeding and there has been clear evidence of that, with six new individuals detected either in traps or on camera in recent months.

Please help save the chuditch

You can help Australian Wildlife Conservancy continue its chuditch translocation program, vital to the ongoing survival of the species, by contributing funds to Australian Geographic Society’s Australia’s Most Endangered campaign.