The Canning Stock Route

I COULDNT’ HELP IT. I stopped the 4WD on the crest of a steep ridge of fine red sand and stepped out into the late afternoon sunlight, which had tinged the sea of spinifex and the forest of flowering holly grevillea with a rich hint of gold. To the north, line after line of dunes marched away to the horizon, while far to the south a sparkling glint of silvery white marked the northern expanse of Lake Disappointment’s vast salt-encrusted bed.

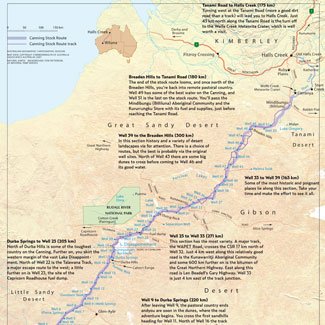

Most people have similar feelings when they travel this fabled remote track. Maybe it’s the wide open spaces where a person’s sense of freedom can seem to soar on open wings; maybe it’s the history that oozes out of the sandhills, like the grains of sand that trickle down their steep flanks; maybe it’s the challenge of travelling in such a remote place; or just the joy of getting over the dunes successfully. Whatever, the Canning Stock Route (CSR) continues to lure well-equipped modern adventurers to the golden aura of its 1800 km of sandy track from central to north-western WA, through the Little Sandy, Gibson, Great Sandy and Tanami deserts.

I first travelled the Canning back in the mid-1980s and have returned many times since. Still, this trip – on which I led an Australian Geographic Society 4WD tagalong tour – was the first time in 10 years I’d driven the stock route’s full length and it was great to once again soak up the history that pervades the track, and to marvel at the changes of vegetation and habitat along its course.

For the first few hundred kilometres north of Wiluna, the CSR runs through the mulga scrubland of pastoral properties. Bar the occasional fellow traveller, it’s completely deserted, dotted sparsely with the original wells that make up the stock route and the scattered bores and windmills of the cattle stations.

From Well 14, the long east–west sand ridges stretch to the horizon, and the roller-coaster ride begins. Up to about 15m high, the dunes are dominated by spinifex grasslands. Water points become welcome rest stops and mini-oases, attracting wildlife and dusty travellers. Durba Springs is probably the most popular campsite and few people stay here just one night, taking a day or two to explore the area’s hidden pools of water, narrow gorges, sheer cliffs, ancient Aboriginal art sites, and engravings of explorers and drovers. Dingoes sometimes skulk among the verdant vegetation and camels often quench their thirst at the permanent waterhole close to the gorge’s entrance.

Canning Stock Route View large map

North from the Durba Hills the sea of sand is tossed into huge mounds, like waves cresting over a shallow shoal, creating some of the biggest dunes on the CSR. Among the red sand and silver-gold spinifex, the blooming desert holds forests of holly grevillea and the mauves and pastels of mulla-mullas, the bright yellow blooms of wattles and, in places, the flash of brightly coloured daisies.

Push on to Well 33 and the terrible corrugations are seemingly capable of rattling teeth out of even healthy gums. Few groups cross this stony plain without some vehicles falling foul of the badly rippled earth. Then, through the northern section of the stock route, many of the wells shelter dark stories in their recesses. Roughly marked graves indicate the last resting places of those who died from illness or were killed by Aboriginals protecting their meagre water supplies. Many of these wells have now fallen in or been burnt down, or both, and only a few have been restored.

For many travellers today, the last blessed night on the stock route is beside the grass-fringed Lake Gregory, and the contrast between the desert country to the south and the vast lake, alive with birds, is something to behold. The lake hasn’t been completely desiccated for more than 20 years.

There’s always a sense of melancholy as you drive onto the Tanami Road and leave the CSR behind. But it’s outweighed by the rich tapestry of experiences enjoyed, vistas seen and marvelled over, people met and feelings shared.

Desert art on the Canning Stock Route

“What all this is telling me,” says Dr Shaun Canning as he inspects the well-weathered grooves of an ancient piece of laboriously pecked rock art depicting what could be a stylised human figure, “is that this place has been continually visited and possibly inhabited for the past 15–25,000 years.”

Shaun, great grand-nephew of the Alfred Canning whose stock route we are travelling, is an archaeologist and anthropologist whose work in recent years with the Adelaide-based firm, Australian Cultural Heritage Management Pty Ltd, has centred on the lifestyles and art sites of the Aboriginal people of Central Australia and the Pilbara. He was now on his knees investigating some art not far from Onegunyah Rockhole, just to the south-west of the great bulk of sparkling salt that is Lake Disappointment. Once, in the time frame that Shaun is talking about, the lake would have been full of fresh water and the country vastly different from what we see today.

“See this,” Shaun exclaims as he moves to another find. “This is an ancient anvil – you can see the strike marks on its surface. This could have been in use anywhere in the last 5–10,000 years when we first see the microlithic bipolar flaking style of toolmaking come into being.” Scattered around the anvil were small discarded shards of quartz. Lifting his hand as if to strike the rock, Shaun continues: “It was a great technological leap forward. Here they would hold a piece of quartz on the anvil and strike it with a rock hammer-stone, causing the quartz to shatter along a planned set plane.”

Nearby, weathered engravings detail large fish, animal tracks, a man-like figure, a large caterpillar and enigmatic circles and lines, many of their meanings lost over time. In one area there are well-worn grooves, the result of tool sharpening, while all round are the scattered flakes of discarded stone tools. “At the height of the ice age about 18–20,000 years ago, this country was drier, colder and windier than what we see even now,” Shaun explains. “The lake would have dried and life would have been much tougher, but these ancient people still survived – they were masters of their environment.”

Canning Stock Route established

With Aboriginals as guides, 46-year-old surveyor Alfred Canning trekked north in 1906 to establish a route that would eventually bear his name. He was endeavouring to find a way by which East Kimberley cattle could be taken to southern markets. Previous explorers Lawrence Wells and David Carnegie – who had both lost men on their expeditions in the area – advised against continuing the search for such a route. “We have demonstrated the uselessness of any persons wasting their time and money in further investigations of that desolate region,” Carnegie wrote.

But at the instigation of the Secretary for Mines, Canning set out from Wiluna with seven other men, 23 camels, two ponies, 2.5 tonnes of provisions and 1440 L of water. During the ensuing 14-month survey the team trekked about 4000 km, often relying on the Aboriginal guides to help them find water.

On his return, Canning reported that a stock route could be established with fair feed and good water from 52 wells and watering points. In 1908 he sank the wells. Working in temperatures of around 50°C for weeks at a time his crew completed 51 wells, averaging one every 18 days. The deepest was Well 5, at more than 30 m; the shallowest, Well 42, was just 1.4m.

Many of the wells are now little more than depressions in the ground and some have their water tainted with the corpses of rotting animals. But according to Kevin Atkins, one of the last surviving white drovers to have taken cattle down the Canning, non-functioning wells were fairly common: “Three or four of the wells along the route were out each time.” He quietly describes the three 12–16-week drives he did back in the early 1940s from south of what is now Old Halls Creek to Wiluna, two of them with legendary drover Wally Dowling. “We’d push the cattle along.

The cattle would drag their bums on the steep dunes – they’d stagger up and we’d cover 10–12 miles [16–19 km] a day.”

Most of the 31 mobs of cattle that were taken down through the desert up to 1959 were mustered on Billiluna and Sturt Creek stations, out of Halls Creek.

Getting water up from the wells was hard work and the drovers would use a camel to ‘whip’ the water up in a 12-gallon (50L) canvas bucket – the often-seen steel buckets at each well weren’t favoured by the stockman.

“You couldn’t hold the cattle back from the wells,” Kevin says. “They’d rush to get to the water especially after three or four days. They wouldn’t go anywhere though and you’d just have to get the water up and into the troughs.”

Once in Wiluna, Kevin would gather a mob of brumbies from stations such as Carnegie and head back up the stock route, selling them far and wide throughout the Kimberley. “We’d travel faster with the horses,” he says. “It was an eight-week trip back and we’d bring 40–60 horses back with us. Horses were in short supply in the Kimberley ’cause of the ‘walkabout disease’ that was prevalent then.” Descendants of those brumbies still roam the Kimberley today and none are fatter or as well off as the wild horses around Lake Gregory at the northern end of the CSR.

New phase for the Canning Stock Route

In the 1960s the track began its new phase as the premier route for vehicular adventures. By the early 1980s, more than 100 people were travelling it each year. It’s estimated that more than 500 vehicles made the trip last year.

The first full-length traverse of the Canning by vehicle was in 1968, but four years prior to that, Henry Ward became the first person to travel by vehicle up the stock route as far as the Durba Hills and Well 18. “We went up in a four-cylinder Land Rover,” he says. “We set up a fuel dump out near Well 11 and followed cattle pads between the wells.”

Henry had previously established Glen-Ayle station, a remote property at the southern end of the Canning. Its 3040 sq. km straddle the stock route between Well 7 and Well 11.

“I took up the lease in 1947 and arrived out here a year later – I was 28,” Henry says. “There was a pile of kids around at home [near Wiluna] and after WW II I thought I wanted a bit of land of my own, some cattle and horses, so I went bush. I had a blackfellow with me and a few packhorses and we came out to look over the country that had been recommended to me.”

He and his son Lou now run 4500 cattle and a few sheep on the property, but wild dogs have dramatically cut sheep numbers. “We’ve probably lost close to 3000 sheep in the last couple of years,” Lou says. “You just can’t keep sustaining those losses and, while we bait and shoot, the dogs look like winning.”

But Henry is adamant the Ward dynasty won’t be giving up on its patch of revered scrub in the near future. “There’s country wasted out here…not waste country,” he says.

Capricorn on the Canning

“You can’t believe the changes,” says Jock Hutchison, the manager of Capricorn Roadhouse and the driver of the truck that delivers fuel to Well 23 – the dump that has been the lifeline for CSR travellers ever since it was established back in the 1980s. “Last year the area around here [Well 23] was barren and as dry as a chip. This year it’s alive and covered with flowers. It’s amazing.”

Jock is a New Zealander who lost his way 20 years ago while on a trip supposedly to the UK. “Never got any further than here,” he says. “I love it.”

Once every 2–3 weeks during the peak of the Canning season he makes the 487 km, 12–14-hour each-way trip from the Capricorn Roadhouse, near Newman, to service the fuel dump. He also delivers fuel to the Cotton Creek Aboriginal community, Balfour Downs station and the Western Areas mining camp. “This is a way of life – not a job,” he says.

The old Hino 6-tonne truck Jock drives is also equipped for rescuing vehicles beaten by the Canning. “The furthest out we’ve had to do a recovery while I’ve been at Capricorn was down near Well 22,” he says. “It was a 100-series Cruiser and the sandhills were a bit of a problem. We had to wait for evening until the sand cooled before we could get over them.”

Despite the tyranny of distance, the Aboriginal community of Kunawarritji was established in the 1980s a few kilometres from Well 33, by people wanting to return to their traditional lands. The community’s assistant chairperson, Stephen Peterson, says the community of 100 or so is primarily made up of people who moved or were shifted from their lands when they were young. “This is my father’s country,” he says. “My mother’s country is to the north-west, but all these women, some of who are my aunties, they all have a story to tell.” Struggling to survive in a whitefella’s world, they’d worked on cattle properties and many ended up living on the outskirts of the bigger towns closer to the coast. However, each had an unquenchable desire to come back to their country.

Now that they’ve returned, they’re happy and more than willing to welcome visitors to their community. As travellers across their land we have an obligation to help, and just buying some fuel and supplies or, better still, a piece of desert art, will help them stay on their land and return some of the dignity they so richly deserve.

Five days after leaving Kunawarritji, as our journey came to a close, the shimmering waters of Lake Gregory slipped behind us and the tangible tug of civilisation could be felt by all in the party. The Canning and its surrounding desert country had touched our soul and seeped into our very being, bringing us closer to nature, the country and the history that intertwines with it all.

All I felt like doing was turning around and heading back down the track.

Source: Australian Geographic Jul- Sep 2007

RELATED STORIES