Darwin, Wallace and the princess in the south

THE POPULAR MISCONCEPTION goes something like this: the young Charles Darwin, on the voyage that shapes his concept of evolution, visits a fledgling Australia in 1836 to study its unique wildlife. Australia in turn honours the great man and his world-changing theories by naming its northernmost city after him.

The trouble with such a story is that it wouldn’t be entirely true. Certainly the NT capital bears his name, but only because the natural harbour around which it sprawls was named Port Darwin in 1839 by a shipmate of Darwin’s who was the captain of the Beagle’s subsequent surveying voyage, 30 years before any settlement was founded and 20 years before Darwin spoke publicly about evolution. And Darwin appears to have had mixed emotions about Australia. His parting shot in The Voyage of the Beagle, his best-selling published journal of the trip, is often quoted:

“Farewell, Australia! you are a rising child, and doubtless some day will reign a great princess in the south: but you are too great and ambitious for affection, yet not great enough for respect. I leave your shores without sorrow or regret.”

Before we succumb to despair, it’s worth noting that Darwin disliked many of the places he visited during his time aboard HMS Beagle. New Zealand came out far worse, Darwin finding it neither pleasant nor attractive and ranking its Englishmen “the very refuse of society”. He was too homesick after four long years abroad to muster up much enthusiasm for new lands, and looked back more fondly on Australia in later diary entries and letters, eventually deciding that Australia was a “fine country”.

The Voyage of the Beagle has more to say about convicts and squatters than parrots or kangaroos, but Australia did influence Darwin’s thinking about evolution; it rates more than 20 mentions in On the Origin of Species and as many again in its sequel, The Descent of Man. Ultimately, Australia has mattered much more to evolutionary thought than this might imply; the other great man who conceived of evolution by natural selection, Alfred Russel Wallace, wrote at length about Australasian fauna, and Australian scientists are currently at the forefront of research based on the most fundamental evolutionary concepts.

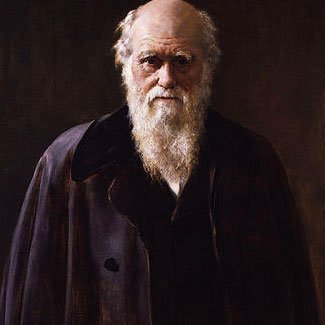

Charles Robert Darwin. A copy made by John Collier (1850-1934) in 1883 of his 1881 portrait.

TWO HUNDRED YEARS have passed since Charles Darwin’s birth, and 150 since the publication of his revolutionary book, On the Origin of Species. What should we think about this amazing man who chose to sneer at Australia? The biologist in me salutes Darwin for providing the core idea around which biology could grow into a major scientific discipline. Darwin gave people new ways to think about themselves, their “animal” origins and their place in the world. But our antipodean gratitude should also go to Alfred Russel Wallace, whose defining essay on the topic was written during travels in the Australasia region.

Darwin was not, as is often supposed, the first to conceive of evolution. His grandfather Erasmus was one of many before him to argue for the concept. Darwin’s contribution was to identify natural selection as the mechanism that drives evolution, by recognising that many are born but only the best suited survive and reproduce. Darwin explained this in Origin, an accessible and easy-to-read book at a time when Europe was in the midst of a golden age of discovery and scientific inquiry.

The Beagle expedition’s main task was to provide Britain with better charts of South America. During the three and a half years of detailed survey work in those waters, Darwin, the ship’s self-funded naturalist (he’d had to pay much of his own way), pondered the forces that had shaped the continent. Geology was Darwin’s first passion and the glamour science of that era. On his return to London, he convinced the Geological Society that the Andes were slowly rising, thereby ending the long-standing debate between the Catastrophists, who interpreted landscapes as the work of rare cataclysms, and the victorious Uniformitarianists, who argued that geological formations are the result of constant slow-moving processes still occurring.

Knowing this, it’s no surprise that Darwin was most enthusiastic about Australia, not when he was admiring a finch or rat-kangaroo, but when he scaled the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney. He recorded his impressions in a book devoted to geological observations on his voyage:

“It is not easy to conceive a more magnificent spectacle, than is presented to a person walking on the summit-plains, when without any notice he arrives at the brink of one of these cliffs, which are so perpendicular, that he can strike with a stone (as I have tried) the trees growing, at the depth of between 1000 and 1500 feet [305–457 m] below him; on both hands he sees headland beyond headland of the receding line of cliff, and on the opposite side of the valley, often at the distance of several miles, he beholds another line rising up to the same height with that on which he stands, and formed of the same horizontal strata of pale sandstone.”

The Beagle had sailed into Sydney on 12 January 1836, and Darwin crossed the Blue Mountains on a trip to Bathurst to glimpse the country’s interior. He slept in a cosy inn at Blackheath and descended on superb convict-built roads before staying at Wallerawang homestead by the Coxs River. Here he was fortunate to see platypuses “diving and playing” in the water, although a proper examination of an animal was only obtained by shooting one. Darwin’s private journal also records a reflective moment which anticipated his future thinking:

“I had been lying on a sunny bank and was reflecting on the strange character of the animals of this country as compared with the rest of the world. An unbeliever in everything beyond his own reason might exclaim, ‘Surely, two distinct Creators must have been at work; their object, however, has been the same, and certainly the end in each case is complete’.”

Twenty-three years later Darwin revisited different “creations” in different places in On the Origin of Species. Australia, he would explain, had both living and fossil marsupials, and South America had living and fossil sloths and anteaters, showing that animals on each continent were allied by descent: “We see the full meaning of the wonderful fact, which has struck every traveller, namely, that on the same continent, under the most diverse conditions, under heat and cold, on mountain and lowland, on deserts and marshes, most of the inhabitants within each great class are plainly related; for they are the descendants of the same progenitors and early colonists.”

Darwin didn’t enjoy his destination, Bathurst – commenting in his personal journal about its “hideous little red brick church” – and he was soon on his way back to Sydney. The Beagle sailed on to Hobart, and then to King George Sound in Western Australia. Darwin disliked the vegetation on mainland Australia, describing it as a product of “sterile” soil, and expressing a wish in Voyage to never walk again in such uninviting country. Only in Tasmania was there enough verdure to please his English eyes. A trek up Mt Wellington, behind Hobart, turned sour when the guide chose a difficult route, but the forest was majestic: “In many parts the eucalypti grew to a great size, and composed a noble forest. In some of the dampest ravines, tree-ferns flourished in an extraordinary manner; I saw one which must have been at least twenty feet [6 m] high to the base of the fronds, and was in girth exactly six feet [2 m]. The fronds forming the most elegant parasols, produced a gloomy shade.”

Tasmania was probably in his thoughts many years later when, in Origin, he explained that similar animals found on adjoining lands implied common origins: “Britain is separated by a shallow channel from Europe, and the mammals are the same on both sides; and so it is with all the islands near the shores of Australia.”

After King George Sound, the Beagle sailed to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands (at the time ruled by Captain John Clunies-Ross, but they became Australian territory in 1955), where the captain, Robert FitzRoy, took soundings, and where Darwin pondered the formation of coral atolls and obtained good evidence to support his theory on their formation. Despite seeing pretty fish, Darwin grumbled that coral grottoes had been overrated as places of colour and beauty: “I must confess I think those naturalists who have described, in well-known words, the submarine grottoes decked with a thousand beauties, have indulged in rather exuberant language.” The Beagle then sailed for England, and Darwin’s nearly five years of travel – from 27 December 1831 to 2 October 1836 – reached an end.

AS A MAN OF inherited means, Darwin could devote the rest of his life to independent scholarship. Wallace was born instead into a family of failing fortunes and had to leave home at 13 to make a living. His first attempt to earn income as a naturalist foundered when in 1852 the ship bearing him home after four years in South America caught fire and his notes and thousands of specimens he hoped to sell were lost. After writing a book about his travels and travails, Wallace turned his sights to the East Indies, spending eight years on the islands strung between Malaya and Australia, from 1854 to 1862. While collecting birds and insects, he observed telling differences between islands, as Darwin in the Galapagos had done decades before him.

It was an essay sent by Wallace to Darwin that jolted the older man into action, rushing him into print before he was ready. Wallace had sent his article to Darwin with the intention of it being shown to the eminent geologist Charles Lyell. To Darwin’s dismay, Wallace had grasped the notion of evolution driven by a surplus of individuals, an idea both had developed after reading Thomas Robert Malthus’s “An Essay on the Principle of Population”. Malthus’s radical treatise proved amazingly influential; his comments on overpopulation also convinced Britain that free migration to Australia and other outposts would strengthen rather than weaken English society.

Darwin’s colleagues arranged for Wallace’s essay to be read in 1858 to the Linnean Society in London, together with extracts from two unpublished documents encapsulating Darwin’s thoughts, written by Darwin in 1844 and 1857. Darwin then set about writing the book that would change how people thought about their place in nature. On The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life – to give the first edition its full title – was published the following year.

A book about Australia that was published soon after was among the first to lend support to Darwin and Wallace. Its author, Joseph Dalton Hooker, was a botanist who travelled on James Ross’s Antarctic expedition from 1839 to 1843 and who became one of Darwin’s closest friends and ardent supporters. Hooker’s volume about Tasmanian plants, which drew upon specimens he collected on the expedition, began with a spirited endorsement of natural selection, before summarising Australia’s flora in a volume that remains relevant today. Darwin wrote to tell him it was the most interesting essay on nature he had ever read.

Wallace returned from Asia in 1862. He wrote The Malay Archipelago (1869), followed the next year by Contributions to the Theory of Natural Selection. To illustrate evolution at work Wallace invoked the kangaroo, whose sandy coat afforded a measure of disguise, and Australian seahorses that impersonate seaweed. Wallace proposed that only birds with hidden nests could afford to have colourful females, nominating Australian treecreepers, sitellas, pardalotes and ground parrots as evidence.

Wallace wrote prolifically over the years about many topics, including Australia. He edited a geography book, Australasia, expanded from an earlier publication by a German historian. In one article he proposed an Australian origin for the parrots of the world, an idea lent support by recent DNA evidence, and in another, written for a gardening magazine, he extolled the “very beautiful” eucalypt in his garden in Dorset. Wallace’s knowledge of Australia helped make his name as the world’s foremost biogeographer. He defined the continent largely by what it lacked, as is clear from The Malay Archipelago:

“It is well known that the natural productions of Australia differ from those of Asia more than those of any of the four ancient quarters of the world differ from each other. Australia, in fact, stands alone: it possesses no apes or monkeys, no cats or tigers, wolves, bears, or hyenas; no deer, or antelopes, sheep or oxen; no elephant, horse, squirrel, or rabbit; none, in short, of those familiar types of quadruped which are met with in every other part of the world.”

But Wallace is most famous today for the line that bears his name. Most Australians have seen it on maps without knowing exactly what it means. Passing between Bali and Lombok and Borneo and Sulawesi, Wallace’s Line separates the Asian faunal realm from the transitional zone between Asia and Australia, called Wallacea. Sulawesi, the Moluccas and the Nusa Tenggara chain make up this island domain.

Before a visit to Wallacea two years ago, I delved deeply into Wallace’s Malay Archipelago, and like him I marvelled at the mix of species in Sulawesi’s rainforests. I saw cuscuses, honeyeaters and lorikeets which reminded me of Australia, alongside such typically Asian fare as monkeys, hornbills, and a reticulated python that lunged at my face. I came away full of respect for Wallace, who spent eight trying years in what was then a very remote and unsafe region. The best of the 19th-century naturalists learnt biology the hard way, spending far more time in the field than do most biologists today.

Wallace showed far more interest in Australia than Darwin, but whether or not he actually visited the place depends on how you define it. New Guinea and the Aru Islands, which were two of his collecting grounds, count biogeographically as Australia in the same way that

Tasmania does. But Wallace never set foot on what today is Australian national territory.

DARWIN’S RELATIONSHIP WITH Australia was nothing if not complicated. His servant on the Beagle voyage, Syms Covington, shared his distaste for the convict-tainted culture of Sydney. But although he wrote in his journal that he was “heartily happy to leave” Sydney, Covington emigrated to NSW just a few years later. Darwin armed him with fulsome references, which mentioned his slight deafness – attributed to his employment as Darwin’s shooter, responsible for obtaining specimens. When Darwin decided he needed more credibility as a naturalist before publishing on evolution, he embarked on a major study of barnacles and asked his ex-servant to send him Australian specimens, which Darwin scientifically described. Covington prospered in Australia, eventually becoming a country postmaster at Pambula, on the NSW south coast.

The letters exchanged by the two friends show that Darwin’s thinking about Australia shifted. “Yours is a fine country,” he wrote Covington in 1857, “and your children will see it a very great one.” The letter also refers to Darwin’s dinner in England with Australian sheep-breeder Sir William Macarthur, during which he “drank some admirable” Australian wine. Some years later, feeling more despondent about his life than usual, Darwin wrote to Covington with a most unusual inquiry: “When I think of the future I very often ardently wish I was settled in one of our Colonies… Tell me how far you think a gentleman with capital would get on in New South Wales.”

Australia had evolved into a true princess in the south, a place Darwin thought might be better than England. Darwin so disliked sea travel, and was so often ill, that one can hardly imagine him boarding a ship bound for Sydney, but had he done so On the Origin of Species might have been an Australian book, and this story may have turned out very differently.

Darwin’s legacy is vast. He changed for all time our picture of life on earth and our place in it. Arguing clearly and powerfully from examples drawn from all over the globe, he showed that nature and humanity are not opposing categories but part of the same flourishing of life. He provided nature with a past that explains what it is today. He did the same for us. His influence lives on in disciplines as diverse as medicine, agriculture, philosophy and psychology.

A century and a half after he gave the world his theory, Charles Darwin remains as relevant as ever.

Source: Australian Geographic Oct – Dec 2009