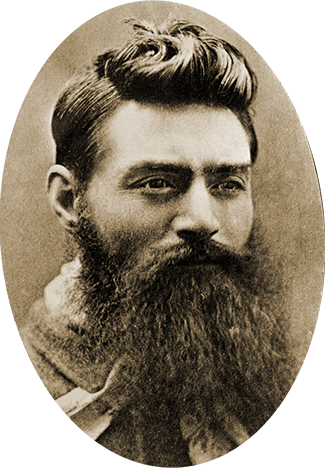

Ned Kelly: Hero or hell raiser?

Finally, 132 years after his state-sanctioned execution, Ned Kelly was re-buried in January 2014 next to his mother, Ellen, in Greta, a small town 10km south of Glenrowan, Victoria.

He was originally buried in the grounds of the Melbourne Gaol in 1880, then reinterred in HM Prison Pentridge in 1929, but Pentridge is currently being developed as a housing estate, so the remains were exhumed – along with others – identified as his, and given to the family.

During his short life, Kelly was a polarising figure, and remains one today – so much so that his family members have taken the precaution of burying him in an unmarked grave.

Many view Kelly not so much as a folk hero but as a convicted murderer responsible for the death of three police officers. They would see it as justice that his victims – police officers Michael Scanlan, Michael Kennedy and Thomas Lonigan – have prominent tombstones and a large memorial in the Victorian mountain town of Mansfield, while Kelly lies in an unmarked grave.

An exploration of Kelly’s life, however, reveals some of the reasons why he became the quintessential Australian folk hero – a bush-loving rebel who stuck it to the authorities.

Ned Kelly’s history

When only 10 years old, Kelly was acknowledged locally as a hero after he courageously saved a seven-year-old boy from drowning. The child, Dick Shelton, had fallen into rain-swollen Hughes Creek, in Avenel, 100km north of Melbourne, when he tried to retrieve his new straw hat, which had dropped off as he walked across a footbridge.

To acknowledge Kelly’s bravery, the Sheltons, who ran the Royal Mail Hotel, presented him with an embroidered green silk sash. Kelly wore this sash in the siege at Glenrowan and his family members wore it in January this year as they read from the scriptures during his memorial mass at St Patrick’s Catholic Church in Wangaratta.

Although Kelly’s official birthdate isn’t known, it’s thought that he was 11 or 12 when his father Red died in Avenel, and it was left to Kelly to register the death at the local telegraph store. Red had been a convict transported to Australia for the theft of two pigs, said to be worth about £6 (about $850 today). After his father’s death, Kelly effectively became the male head of his family – which consisted of his 33-year-old mother and six siblings.

In the following years, Kelly grew to symbolise the industrious and resourceful bush settlers who had learned to live in this harsh country, becoming an expert horseman, bushman and tree feller.

As his exploits became more audacious, he also became a symbol of those early Australians who defied the authority of the Protestant English establishment. At the time of his sentencing by the Anglo-Irish Protestant judge Redmond Barry, 60,000 signatures – one-fifth the population of Melbourne – were collected in protest against his execution. A crowd of 5000 also stood outside the Melbourne Gaol on the morning he was hanged.

The Ned Kelly case in modern day

In recent years, legal experts such as the late John Phillips, former Director of Public Prosecutions and Chief Justice of Victoria, have suggested that, if properly represented, Kelly would have been convicted of manslaughter rather than murder, on the grounds of excessive self-defence. The police officers pursuing him had no arrest warrants, wore plain-clothes rather than police uniform, were intent on claiming the £8000 reward and had no intention of taking him alive.

Following Kelly’s execution, at the age of just 25, the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Kelly affair criticised Chief Commissioner Standish for “his want of impartiality, temper, tact and judgement”. These findings led to the early resurgence of the resentment and antagonism among the Irish Catholic minority, claiming police persecution, in what had already become known as ‘Kelly country’ in north-eastern Victoria.

One could ask why Kelly’s family members have felt it necessary for the Australian icon to be buried in an unmarked grave. It is my belief that it reflects our community’s inability to either forgive or forget.

Peter Norden AO is an adjunct professor at RMIT University and a former chaplain of HM Prison Pentridge.