12 books every Australian should read

THERE’S SOMETHING ABOUT this wide, brown land of ours, fringed by water, that conjures up a powerful sense of place, and how small we can sometimes feel within it. The sheer tough vastness of life in Australia since white settlement is an element that, to greater or lesser degree, permeates the work of most writers who have depicted life here.

An undercurrent of the best Australian writing has always been strong characters, an irreverent voice, and a background of bustling, dirty inner-city suburbs, small, sunbaked rural towns and uneasy tropical communities at the mercy of ferocious weather.

There’s nothing quite like a good book to transport you far away, but why not travel through books a little closer to home?

Here we have a list of 12 Australian stories that really couldn’t have been set anywhere else. Author Alex Miller has written of the outback as “not a place, but the Australian imagination itself” – some of these books will take you to explore it; carrying you back in time from today to the late 1800s, roaming from the coastal cities, through pastoral properties and up to the tropical north, before hitting the sea once more.

1. My Brilliant Career

by Miles Franklin (Text Classics, 2012) first published in 1901

Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin wrote My Brilliant Career when she was only 16 years old, and in doing so she gifted us with a character many suspected was autobiographical: Sybylla Melvyn, a flighty, tempestuous, cynical, funny girl born well before her time, a heroine railing against the social mores of 1890s landholding society in Australia. Henry Lawson himself described My Brillant Career thusly: “the descriptions of bush life and scenery came startlingly, painfully real to me, and I know that, as far as they are concerned, the book is true to Australia – the truest I ever read.”

Sybylla is a bundle of contradictions: a charming tomboy who likes to wear a pretty dress, a self-pitying soul yearning to be loved, yet shunning romance when it presents itself. She grows up on a lush property in NSW until her father buys drought-stricken land in Possum Gully and gambles and drinks away the family’s earnings. Sybylla is sent to live with her grandmother and aunt on a property that sounds like the Australian settler’s holy land, all flowing streams and lush ferns and the warble of birdsong.

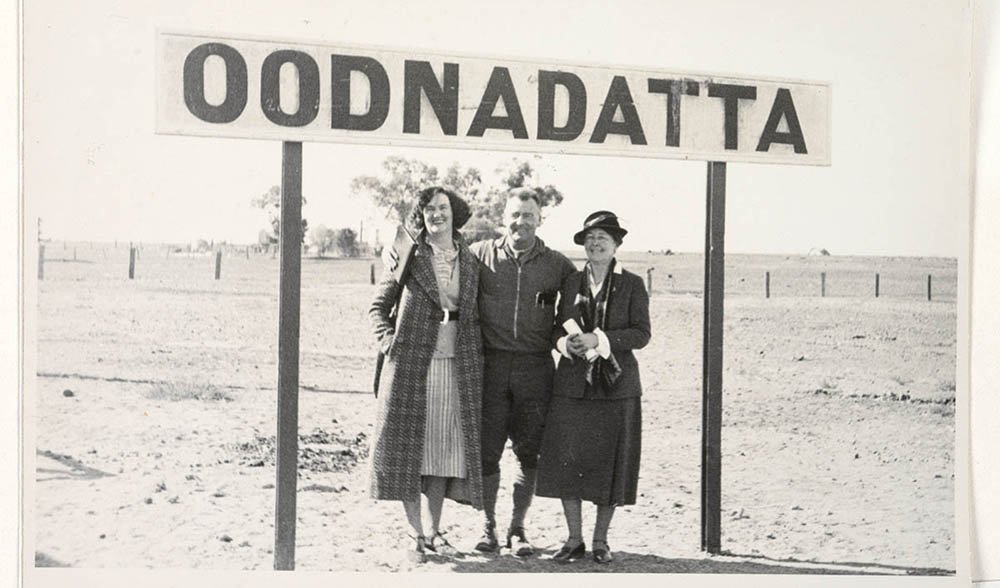

Miles Franklin (right), pictured with fellow Australian author Frank Clune and his wife, art dealer Thelma Clune, in Oodnadatta, outback South Australia. Miles Franklin had a lasting impact on Australian literature through her endowment of the Miles Franklin Award, a major annual prize for literature about “Australian Life in any of its phases”. (Source: State Library of New South Wales / Wikimedia).

This book might be Australia’s answer to a Jane Austen society tale of manners and marriage, except that Sybylla is having none of it. She has a horror of marriage, which she sees as a constraint on her ambitions, and holds firm to her freedom at a potentially enormous personal cost, at a time when the most a woman could hope for was to marry well.

But as the story barrels along, it’s in describing the Australian landscape that Franklin drops Sybylla’s funny, cynical tones for pure poetry, particularly the daily struggle to keep on living on drought-ravaged lands:

Now and again there would be a few days of the raging wind before mentioned, which carried the dry grass off the paddocks and piled it against the fences, darkened the air with dust, and seemed to promise rain, but ever it dispersed whence it came, taking with it the few clouds it had gathered up; and for weeks and weeks at a stretch, from horizon to horizon, was never a speck to mar the cruel dazzling brilliance of the metal sky.

2. The Harp In The South

by Ruth Park (Penguin Books, 2008) first published in 1948

New Zealand-born Park has been a steady Australian favourite for over half a century, and The Harp In The South has never been out of print since it was published.

Reading Park is a crucial part of the puzzle of Australian life – leaping into her yarns written in the vernacular of the day, tackling the stuff of life in a ballsy, earthy, Australian way, where characters pull themselves up by their boostraps and just get on with it.

A former journalist, Park turned to fiction after her children were born and was 28 when The Harp In The South was published. She said she didn’t have much choice in her subject matter, as she only knew Surry Hills people or the newspaper world, and was afraid her fellow reporters would have sued her.

“I didn’t know very much, but I did try to tell the truth as I saw it,” she said in an interview in 1981.

And so she did, creating a big-hearted, warm, no-nonsense portrait of slum life in Surry Hills after World War Two, depicting squalid terrace houses creeping with bedbugs, which smelled of leaking gas and rats and “mouldering wallpaper that had soaked up the odours of a thousand meals”.

The second-generation Irish Darcy family live there: alcoholic father Hughie, long-suffering Ma, and daughters Roie and Dolour, surrounded by a melting pot of local colour: razor gangs, prostitutes, nuns, and ebbing and flowing racial tensions between Anglos and Jews, Aboriginal people and Chinese immigrants.

Park copped a lot of criticism when the book was published, including from Miles Franklin herself, who called it “a shoddy sordid performance of a very phony journalistic book,” full of “catch cries to the gallery”. Park felt a lot of it came because she was a New Zealander, and a woman, writing a social realist book covering issues that few male novelists of the time were game to touch: the female perspective of marriage, sexual politics, physical violence and abortion.

Sequel Poor Man’s Orange was published in 1949, and prequel Missus followed much later, in 1985.

3. Voss

by Patrick White (Random House, 2012) first published in 1957

Voss, a fictionalised account of the Australian expeditions of explorer Ludwig Leichardt, won its author the inaugural Miles Franklin Award in 1957, and is listed on pretty much every “Best Australian Book” list there is. But although White is Australia’s only Nobel Laureate in Literature (winning in 1973), for decades it has been popular to dislike and exile him for what many viewed as his arrogance and elitism.

With a reputation for being difficult, one newspaper review declared White to be “Australia’s most unreadable novelist”. White himself said “I’m a dated novelist, whom hardly anybody reads, or if they do, most of them don’t understand what I am on about. Certainly I wish I had never written Voss, which is going to be everybody’s albatross.”

This book seizes onto the desert as a map of the Australian psyche, as the egomaniacal, megalomaniacal explorer Voss (compared to Faust and Hitler) plans to pioneer an overland route to conquer the country from the east to the west coast. Instead, he vanishes without a trace into the unforgiving desert.

The story links the German explorer with Laura Trevelyan, an orphaned spinster, with whom he strikes up a passionate connection, communicating via dreams and deliriums during their separation as he treks towards his death.

To quote White in Voss: “Knowledge was never a matter of geography. Quite the reverse, it overflows all maps that exist. Perhaps true knowledge only comes of death by torture in the country of the mind.” This ambitious book challenges and ultimately satisfies intrepid readers.

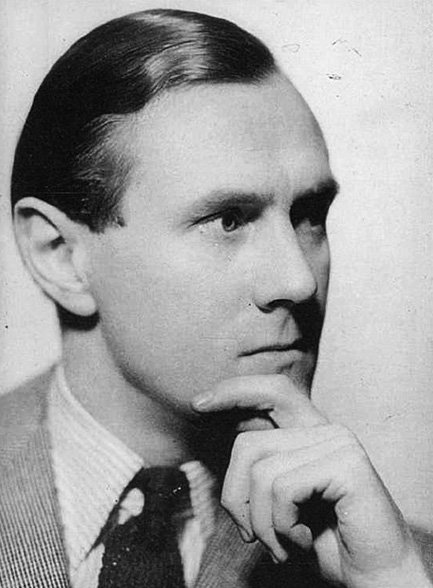

Author Patrick White, photographed in the 1940s. From 1935 to his death in 1990, White published 12 novels, three short-story collections and eight plays. (Source: David Marr, Patrick White: A Life, Random House, 1991, via Wikimedia).

4. Picnic at Hanging Rock

by Joan Lindsay (Penguin Books, 2009) first published 1967

Everyone agreed that the day was just right for the picnic to Hanging Rock – a shimmering summer morning warm and still, with cicadas shrilling all through breakfast from the loquat trees outside the dining room windows and bees murmuring above the pansies bordering the drive. Heavy-headed dahlias flamed and drooped in the immaculate flowerbeds, the well-trimmed lawns steamed under the mounting sun.

So begins Picnic at Hanging Rock, the atmospheric 1900-era mystery surrounding the disappearance of a group of schoolgirls who vanish after climbing the rock. One girl returns with no memory of what has happened, and the small Victorian town becomes consumed with trying to uncover what happened to them, with abduction, sexual molestation and murder all highly rated possibilities.

Fiction dressed up as a true story, part of the book’s enduring is appeal is the did-it or didn’t-it-happen quality to the writing, with Lindsay refusing to confirm that the story was made up, or suggesting that some parts were and some weren’t. She actually wrote a final chapter solving the mystery but was advised by her editor to cut it. It was ultimately published in 1987 after her death as The Secret of Hanging Rock.

The frustrating but dreamy story has captured the imagination of readers for decades. Although it feels like an early 20th century British girls’ boarding school romp, the tone of the book is unmistakably Australian, and often quite cheekily funny.

Lindsay propels the story forwards and backwards, heightening a sense of impending doom and hysteria among the characters, but remains most memorable for its atmosphere of ethereal ambiguity.

The book was adapted into a highly successful film directed to languid, moody effect by Peter Weir in 1975.

5. Cloudstreet

by Tim Winton (Penguin Books, 2007) first published in 1991

This sweeping two-family saga must be one of Australia’s most enduring fictional loves, and was declared an instant classic virtually upon publication 25 years ago, immediately scoring Winton the Miles Franklin Award in 1992.

In 1944, the Pickles family are having a rotten run of luck when they inherit a sprawling house called Cloudstreet in a suburb of Perth. They take on the God-fearing Lambs as tenants, who are reeling from their own tragedies. They open a grocery shop downstairs, and for 20 years the two families live side-by-side, stitching themselves together through births, deaths, adultery, child abuse, mental disability and physical disfigurement, alcoholism, anorexia. Together, not always willingly, they run the whole gamut of the human experience.

Written in a purely Australian vernacular, this is a book to seize you by the heart and shake you around by it until you can’t help but love every one of its characters, the whole flawed, struggling, loving mess of them.

Just near the crest of a hill where the sun is ducking down, the old flatbed Chev gives up the fight and stalls quiet. Out on the tray the kids groan like an opera. All around, the bush has gone the colour of a cold roast. Birds scuffle out of sight. There’s no wind, though the Chev gives out a steamy fart.

This compellingly readable epic easily captures the raucous shared life of Perth during the middle of the 20th century.

6. True History of the Kelly Gang

by Peter Carey (Random House, 2008) first published in 2000

What could possibly be more Australian than that roguish, polarising bushranger himself, Ned Kelly? Peter Carey brings us the fictionalised reimagining of the criminal ringleader’s life in his own words, written as a series of scribblings on bits of scrap paper as an extended letter to his unborn daughter.

The language is a highly constructed artifice creating the picture of a man uneducated but intelligent, written in a sort of colonial patois that nevertheless has a beautiful rhythm to it.

Readers come to the book with the patchy rememberings of the man in the metal armour from schooltime learnings, and Carey fills in the blanks: of how the justice system discriminated against the poor and the Irish, about the difficulties of life on the land, and how a man might be motivated by the love of his family to do some very bad things indeed.

Here we see how a man like Ned Kelly might have become such an enduring cliché of the Australian Robin Hood; the cattle thief and bank robber who became the gold-plated myth of the colonial folk hero, ranging across the farms and forests of New South Wales and Victoria. Is it circumstance, compulsion, or his own doing that makes a murderer of him? Readers will have to read between the lines of this sometimes idealised portrait to decide for themselves.

As he says of his first murder:

I squeezed the fateful trigger. The air were filled with flame and powder stink Strahan fell thrashing around the grass moaning horribly… on the ridges the mountain ash gleamed like saints against the massing clouds but down here the crows and currawongs was gloomy their cries dark with murder.

The New York Times called it “it’s a fully imagined act of historical impersonation.”

7. The Secret River

by Kate Grenville (Text Publishing, 2005)

In 1806, William Thornhill steps ashore in Sydney to make a life for himself after being transported from London as a convict, evading a death sentence but sent to serve out the term of his natural life. His wife and son have come to join him, and several years later, after he wins his freedom, they travel up the Hawkesbury River to start again on a lush patch of land. But Aboriginal people are already living there, and the two worlds will ultimately collide in a horrific massacre on the river banks.

Kate Grenville’s story was based on the life of her ancestor Solomon Wiseman, the namesake of Wiseman’s Ferry. It was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, and she has described it as her attempt to apologise to Indigenous people for the horrors white settlement wrought upon them.

The book looks down the barrel of white settlement and doesn’t shy away from the horrors it finds there, using Thornhill as a prism through which to view people who might have thought of themselves as fundamentally decent, nevertheless capable of great cruelty. But at what cost?

The book has enjoyed enormous success – it is reportedly the most set Australian text on high school reading lists, outpacing Miles Franklin’s My Beautiful Career. It was also commissioned by Andrew Upton and Cate Blanchett as a Sydney Theatre Company play, and was recently adapted for a two-part ABC TV drama.

It was followed by sequels The Lieutenant in 2008, and Sarah Thornhill in 2011.

8. Carpentaria

by Alexis Wright (Giramondo, 2006)

A nation chants, but we know your story already.

So, without pulling any punches, begins Alexis Wright’s epic tale, Carpentaria, a landmark tale of Aboriginal people living in the Gulf country of north-western Queensland.

This country is the home of her people, the Waanyi, and Wright inhabits that world to tell the story of Normal Phantom, patriarch of the Westsiders, who live across town from their east side rivals, led by Joseph Midnight on the other side of the fictional coastal town of Desperance. They sit between officious, unimaginative white bureaucrats and a mine that cuts their own land and mythology out from under them, and in the space between teem the countless stories of the people and spirits that inhabit that place.

There is Normal, the fish-embalming king, his ex-wife the queen of the rubbish dump, the barman who is in love with a mermaid trapped in the wood of his bar, a boxing Irish priest, a murderous mayor, and a fanatical zealot, all jostling to be heard in the wars and uneasy truces between black and white in the remote Top End.

The hefty book throws down the literary gauntlet to readers who are used to more linear storytelling, integrating an atemporal Indigenous worldview with a classical literary fiction sensibility, calling to mind Russian heavyweights such as Dostoyevsky, or the epic feeling of Melville’s Moby Dick, and the Bible itself. Yet it’s very charming, sometimes breathtaking, and often slyly funny.

Carpentaria won the Miles Franklin award in 2007, the same day Prime Minister John Howard announced the Northern Territory intervention, where solders were sent into remote communities to enforce a legislated ban on alcohol and pornography as part of an effort to combat reported child abuse.

This book is an essential read for those who want to understand the mentality of remote communities beyond the headlines and six o’clock news bulletins.

9. A Fraction of the Whole

by Steve Toltz (Penguin Group, 2008)

This bizarre, wonderfully verbose romp is quite unlike any other. It begins with a prison riot and travels from “the least desirable place to live in New South Wales” to a house hidden in a bush labyrinth, to strip clubs, a mental institution, Paris, a jungle in Thailand and ultimately onto an ill-fated journey on a people smuggler’s boat.

This Man Booker Prize-shortlisted madcap, relentless story follows Jasper Dean as he tries to make sense of the life of his depressed, insane father Martin, who tried to make every Australian a millionaire yet became one of the country’s most hated politicians. His story is in lockstep with his brother Terry, Australia’s most loved career criminal, who went on a killing spree based on a desire to wipe out corruption in sport.

The book whirls from set-piece to set-piece, from one bizarre encounter to another as Toltz’s incredible imagination spews forth with blackly comic philosophical musings and boiling with brilliant ideas about life in all its tortured forms.

In a typically hilarious passage, Jasper makes an observation about the “tyranny of distance” that Australia grapples with in relation to the rest of the world:

Australia is like a lonely old woman dead in her apartment; if every living soul in the land suddenly had a massive coronary at the exact same time and if the Simpson Desert died of thirst and the rainforests drowned and the barrier reef bled to death, days might pass and only the smell drifting across the ocean to our Pacific neighbours would compel someone to call the police. Otherwise we’d have to wait until the Northern Hemisphere commented on the uncollected mail.

10. Jasper Jones

by Craig Silvey (Allen & Unwin, 2010) first published in 2009

Jasper Jones has been called Australia’s To Kill A Mockingbird, and certainly there are parallel simmering tensions over one summer in the 1960s in a small town in Western Australia.

Late one night, bookish 13-year-old Charlie Bucktin is startled by a knock on his window by no other than Jasper Jones – “a Thief, a Liar, a Thug, a Truant… he’s the rotten model parents hold aloft as a warning; This is how you’ll end up if you’re disobedient”.

Jasper needs Charlie’s help. He is Aboriginal, and Charlie’s other best friend Jeffrey Lu is Vietnamese, both standing as outcasts in a town where the mine employs half the people and the power station takes the rest. It’s not a good summer to be an outcast, after a girl is found dead, her body dumped at Jasper’s house. The boys have to uncover who is trying to frame him, in a small town where racism runs deeper than anyone would like to admit, during a heatwave as the town goes into meltdown, the Vietnam War hitting closer to home than anyone would have dreamed.

Nerdy, introspective Charlie escapes through literature, seeking solace in the novels of southern American writers William Faulkner, Harper Lee, Flannery O’Connor and Mark Twain. He’s an unlikely hero coming of age in a town with strict social expectations, occasionally testing his parents and gently falling in love.

Jasper Jones isn’t simply sepia-tinted nostalgia, but stares into the face of the cruelty, intolerance and prejudice that stem from ignorance and fear. It’s unflinchingly honest, so highlighting the courage of its young protagonists, who forge a bond in the face of a community that fears what it does not know, and come out of it all the stronger.

11. Autumn Laing

by Alex Miller (Allen & Unwin, 2011)

Not unlike Sybylla Melvyn in My Brilliant Career, here two-time Miles Franklin Award winner Alex Miller gives us a grumpy, irascible, thoroughly charming woman at the other end of her life. Autumn Laing is 85 and well beyond sugar-coating things as she grapples with infirmity, a sassy nurse and an annoyingly nosy biographer, but a chance encounter has her casting back to remember her affair, half a century before, with budding artist Pat Donlan.

The love affair is loosely based on the real-life romance between artist Sidney Nolan and arts patron Sunday Reed, and Autumn takes an unflinching look at what her passion for the 10-year-younger Pat – angry, raw, untutored in art – did to her kind, restrained husband Arthur, and his young wife Edith.

This emotional turmoil is set in rural Victoria in the 1930s, in an Australian art world during the modernist movement that was shaking off the shackles of European conventions to develop something all of its own. But the landscape is a vivid companion, whether surrounding Autumn’s cottage at the end of her life, or the rolling Australian farmland and bush that engulfs the home she shares with Arthur, or the Northern Queensland country around Rockhampton where Autumn and Pat escape to create a frenzy of art, as he discovers his own, uniquely Australian form of expression in the outback and launches an international career.

One of the most beautiful passages in the book, from Autumn’s diary entry of her time in Queensland, captures the breathtaking magic of Australia:

Australia was revealed to me as an elaborate multi-coloured etching; the vision of an unknown artist’s eye. A portrait of my country unfamiliar to me, wrinkled and crumpled, scratched and scoured, broken with abrupt shifts of tone and form, stains and inexplicable runs of colour one into the other, purple and rose madder, vast swathes of grey and fierce angry dragon spots of emerald green…

12. The Narrow Road to the Deep North

by Richard Flanagan (Random House, 2014)

The most recently published book of this list, it netted Flanagan the Man Booker Prize in 2014 for this story based in part on his father’s experience as a Japanese prisoner of war forced to build the Thai-Burmese “Death Railway” during World War Two.

Before the war takes him in the early 1940s, young surgeon Dorrigo Evans has an affair with his uncle’s wife Amy. This relationship becomes his sustaining life force for the next half a century, beginning with his service in the army and eventual capture by the Japanese, taking him to the steaming jungle where allied men suffered immensely under cruel overseers, Dorrigo trying to keep them alive as one by one his men died of starvation, disease, and beatings.

The book brings us the views of other men such as Jimmy Bigelow and Darky Gardiner, as well as those of two Japanese officers, Major Nakamura and the Korean Colonel Kota, who also suffer in the jungle, dampening their pain with drugs and alcohol and, trapped in a rigid hierarchy, brutally lashing out at their captives.

Beginning on the sunlit beaches of South Australia, passing through rainswept Tasmania, to a nightmarish bushfire on Mount Wellington, and ending on a dappled Sydney Harbour Bridge, this book is as much a story of Australia at war as it is the story of one man’s ruin and unhappiness.

Ultimately, however, it is a story of love: romantic love, familial love, and the life-sustaining bond that keeps men hopeful and alive in the most inhuman of circumstances.

READ MORE

- Archer Russell: Australia’s unknown literary great

- Charles Dickens took inspiration from Australia

- Online obituary database reveals Australian stories