Where did the drop bear myth come from?

Have you ever plastered Vegemite all over your face? It’s not the most fetching look and can take some time to scrub off.

However, over the past 40 years that’s exactly the look many a visiting US soldier has willingly worn. According to their so-called Aussie allies, smearing your cheeks and forehead in the yeast extract reduces the risk of being attacked by a drop bear. After all, no-one wants to be ripped to shreds by that carnivorous, long-fanged relation of the koala that can silently drop from trees onto their unsuspecting prey, do they?

In recent years, similarly peculiar precautions offered by sniggering Aussies to innocent international soldiers and tourists have almost become as comical as the myth of the fabled creature itself.

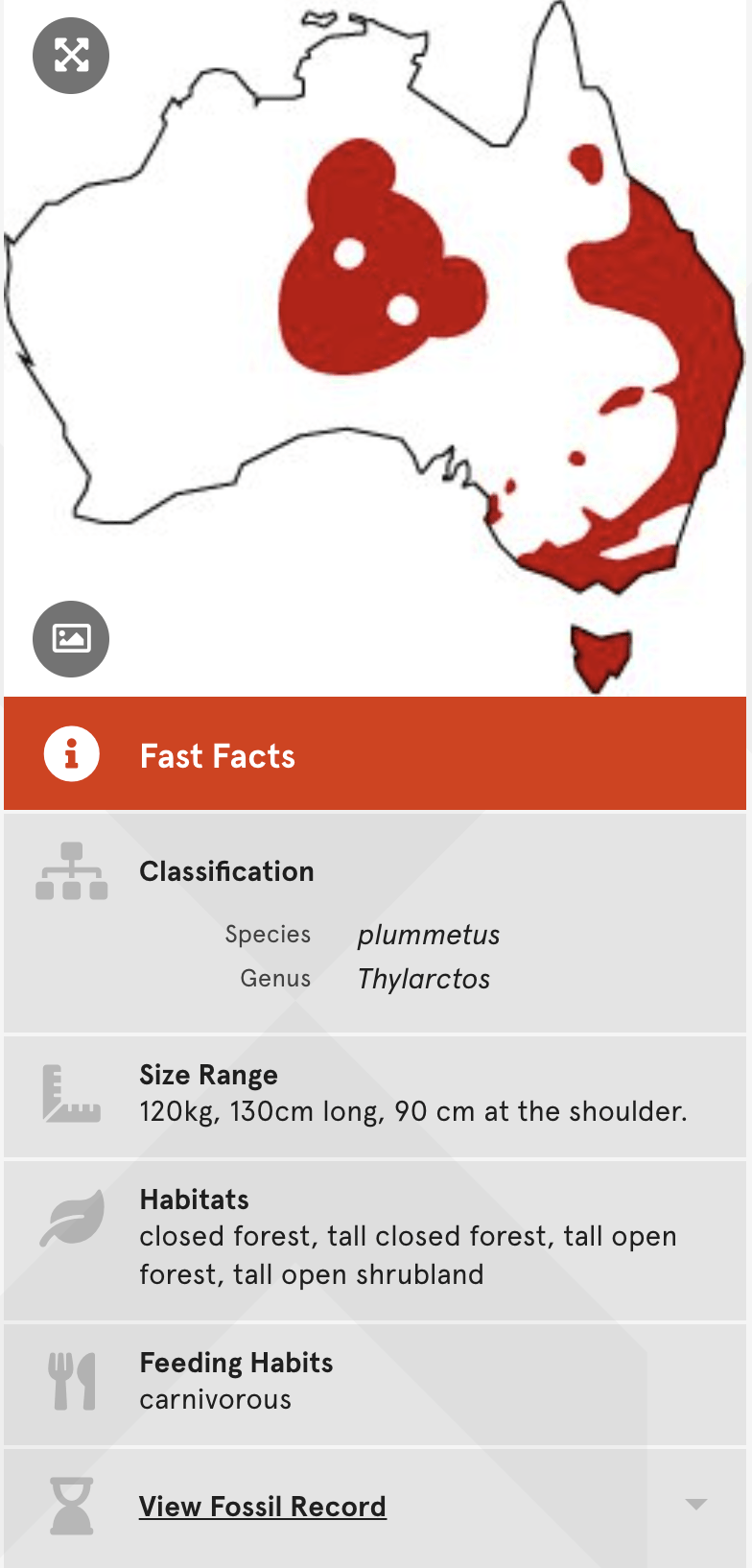

On their official website, the Australian Museum, which even bestows the dastardly denizen of our forests a scientific moniker (Thylarctos plummetus) provides further practical advice to visitors. “There are some suggested folk remedies that are said to act as a repellent to Drop Bears, these include having forks in the hair or toothpaste spread behind the ears,” it states.

While these novel actions to prevent an attack have been well-publicised, the actual origins of the drop bear myth aren’t quite as well-known. That’s because, like any good legend, its beginnings are clouded in the mists of time.

What we do know is that the term ‘drop bear’ didn’t appear in newspapers until 1982 when the following message was published in the 21st Birthdays column of The Canberra Times on 31 July. “TAM — Beware of drop bears in the future, for sure, totally love Clint,” it intriguingly stated.

Who exactly were TAM and Clint? We may never know. Perhaps TAM was the victim of the army prank that was sometimes played on new cadets as well as international troops. Or perhaps he was a fan of The Drop Bears, a post-punk, melodic-pop band that formed in Sydney a year earlier.

Despite the term ‘Drop Bear’ not being published before the early 1980s, there is, however, a tantalising trail of evidence that indicates the foundations for the myth may have been established at least 50 years earlier.

“Numerous fictional fantasy stories published in newspapers in the 1920s and ’30s describe attacks and aggressive interactions by koalas with people,” a spokesperson for the Australian Government Department of Defence says. “It is likely these stories were built upon during World War II and then matured in the 1970s and ’80s after which the term drop bear has become more widespread.”

“For example, a newspaper article from 1943 describes a training program for junior leaders that encouraged the trainees to look to the tree tops to spot snipers and they were encouraged to do so by the training staff dropping small explosive charges on to them at random times. The other form of encouragement was a payment of two shillings for every koala they spotted,” says the well-informed defence spokesperson.

There are also numerous articles from 1946 including a report found in a Japanese controlled Burmese newspaper that describes an attack at a prisoner of war camp in Australia holding Japanese POWs by a number of vicious and savage koalas. Really!

According to the defence insider, “the report describes how the Australian guards cowered in fear while the brave Japanese prisoners fought off the koalas, an act for which they were rewarded. There are various versions of the story that have the prisoners either using the guards’ rifles or bamboo sticks to fight off the koalas and also varying types of rewards.” Heck.

So, what caused the legend that was mainly part of army lore to jump into popular culture in the late 1970s and early 1980s? Well, it seems leading the charge was none other than that dynamic doyen of mid–late 20th-century Aussie larrikinism, Paul ‘Hoges’ Hogan.

In a parody of the first Indiana Jones film, Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), Hoges featured drop bears in a skit in his television comedy, The Paul Hogan Show. In the slap-stick segment ‘Cootamundra Hoges’ endured “untold horrors of the Australian bush” including being attacked by killer koalas silently dropping out of trees. Classic drop bear behaviour according to the Australian Museum website.

While Hoges’ killer koalas weren’t explicitly called drop bears, one person who is in no doubt that this skit was central to perpetuating the myth is Ian Coate.

“There wasn’t much else on TV back then so virtually the whole of Australia was watching it,” recalls Ian who runs Mythocreatology, a website that delves into the spurious past of a long list of Australian myths.

“What I really like about the drop bear is that it’s something that all Australians can embrace – from Indigenous to European, from young to old, it’s something that’s common for all of us,” says Ian.

In fact, Ian reckons the drop bear is a bit like the very breakfast spread recommended as its deterrent.

“Just like Vegemite, we Aussies all know about it, but for someone from overseas it’s quite a foreign concept,” he explains, adding “and in a country crawling with so many other dangerous animals like snakes, spiders and crocodiles, for the uninitiated international visitor the drop bear can sound like a plausible threat.” Indeed.

Regardless of its true origins, in today’s proliferation of digital and social media the drop bear has a rosy future. According to the authors of Man-Eating Teddy Bears of the Scrub: Exploring the Australian Drop Bear Urban Legend, “the drop bear has acquired a place within the digital legend cycle and the internet has become one of the most popular domains for the dissemination of this urban legend”.

Long live the legend of the drop bear.