The Uluru Statement from the Heart: Voice, Treaty, Truth

After centuries of resistance to European colonisation, and decades of activism fighting for equality, Australia’s First Nations people were finally, in 2015, invited by the federal Australian government to advise parliament on how to work towards a referendum to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Australian Constitution.

The Referendum Council was appointed by then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and the Leader of the Opposition Bill Shorten.

Its members spent six months travelling the country, speaking with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people at a series of meetings they called ‘The Dialogues’.

In May 2017, over 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander delegates from Indigenous nations across the country met for the First Nations National Constitutional Convention.

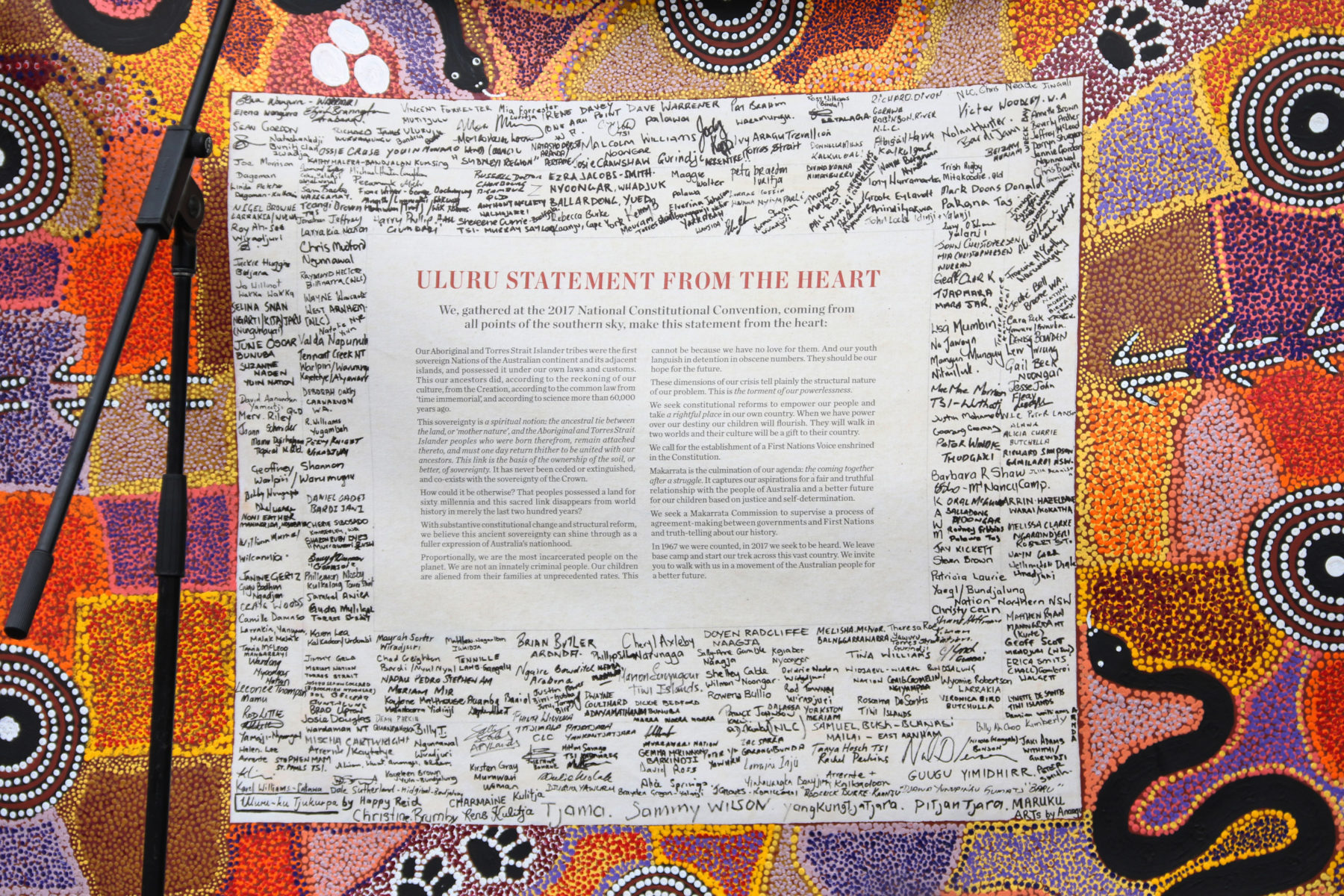

It was during this gathering that the delegates reflected on the insights garnered from The Dialogues, spending days penning and perfecting a 440-word statement – The Uluru Statement from the Heart.

On the morning of May 26 the delegates gathered at the base of Uluru, put their signatures on the statement, and presented it to the nation in what was an incredibly significant moment in our country’s history.

What is the Uluru Statement from the Heart?

The Uluru Statement from the Heart made a series of recommendations, or ‘invitations’ to the Australian people, asking for three sequential key reforms: Voice, Treaty and Truth.

Voice

The first thing the statement calls for is “the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution”.

This ‘voice’ would be in the form of a group of First Nations people, representing all Indigenous Australians.

The government would need to consult with this group on policy and legislation, giving First Nations people the opportunity to have their opinions and preferences heard about laws that impact their country and people.

The reason the statement specifies that the First Nations Voice must be written into the constitution is so it cannot be removed by any future governments.

If Australia was to move forward with enacting this First Nations Voice the country would need to hold a referendum to make any amendments to the constitution.

Treaty

After the establishment of a First Nations Voice, the Uluru Statement from the Heart proposes the creation of a Makarrata Commission – ‘makarrata’ meaning ‘the coming together after a struggle’.

The first goal of this commission would be to oversee and supervise the negotiation of a treaty between colonial Australians and the traditional owners of Australia.

Truth

The second objective of the Makarrata Commission would be to facilitate a truth-telling process to recognise and record past injustices suffered by Indigenous people.

The formal acknowledgment of an agreed truth would then make way for “a fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia”.

The full statement:

We, gathered at the 2017 National Constitutional Convention, coming from all points of the southern sky, make this statement from the heart: Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and customs. This our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation, according to the common law from ‘time immemorial’, and according to science more than 60,000 years ago. This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown. How could it be otherwise? That peoples possessed a land for sixty millennia and this sacred link disappears from world history in merely the last two hundred years? With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood. Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people. Our children are aliened from their families at unprecedented rates. This cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. They should be our hope for the future. These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is the torment of our powerlessness. We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country. When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country. We call for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution. Makarrata is the culmination of our agenda: the coming together after a struggle. It captures our aspirations for a fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia and a better future for our children based on justice and self-determination. We seek a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations and truth-telling about our history. In 1967 we were counted, in 2017 we seek to be heard. We leave base camp and start our trek across this vast country. We invite you to walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future.

What next?

Five years since the The Uluru Statement from the Heart was presented to the Australian people, no formal progress has been made on any of the recommended key reforms.

However, with last week’s change in federal government comes new hope for advocates of the statement.

Newly elected Prime Minister Anthony Albanese affirmed his and his government’s commitment to a referendum on constitutional change during his victory speech the night of the federal election.

“We will, of course, be advancing the need to have constitutional recognition of First Nations people, including a Voice to Parliament that is enshrined in that constitution,” he said.