The mountain ranges of Grampians National Park rise in silencing grandeur from the arid Wimmera Plains as a pulse-line of peaks and troughs. This is the most south-western point of Australia’s Great Dividing Range: 1672sq.km of rocky plateaus and rugged bushland, three hours drive from Melbourne.

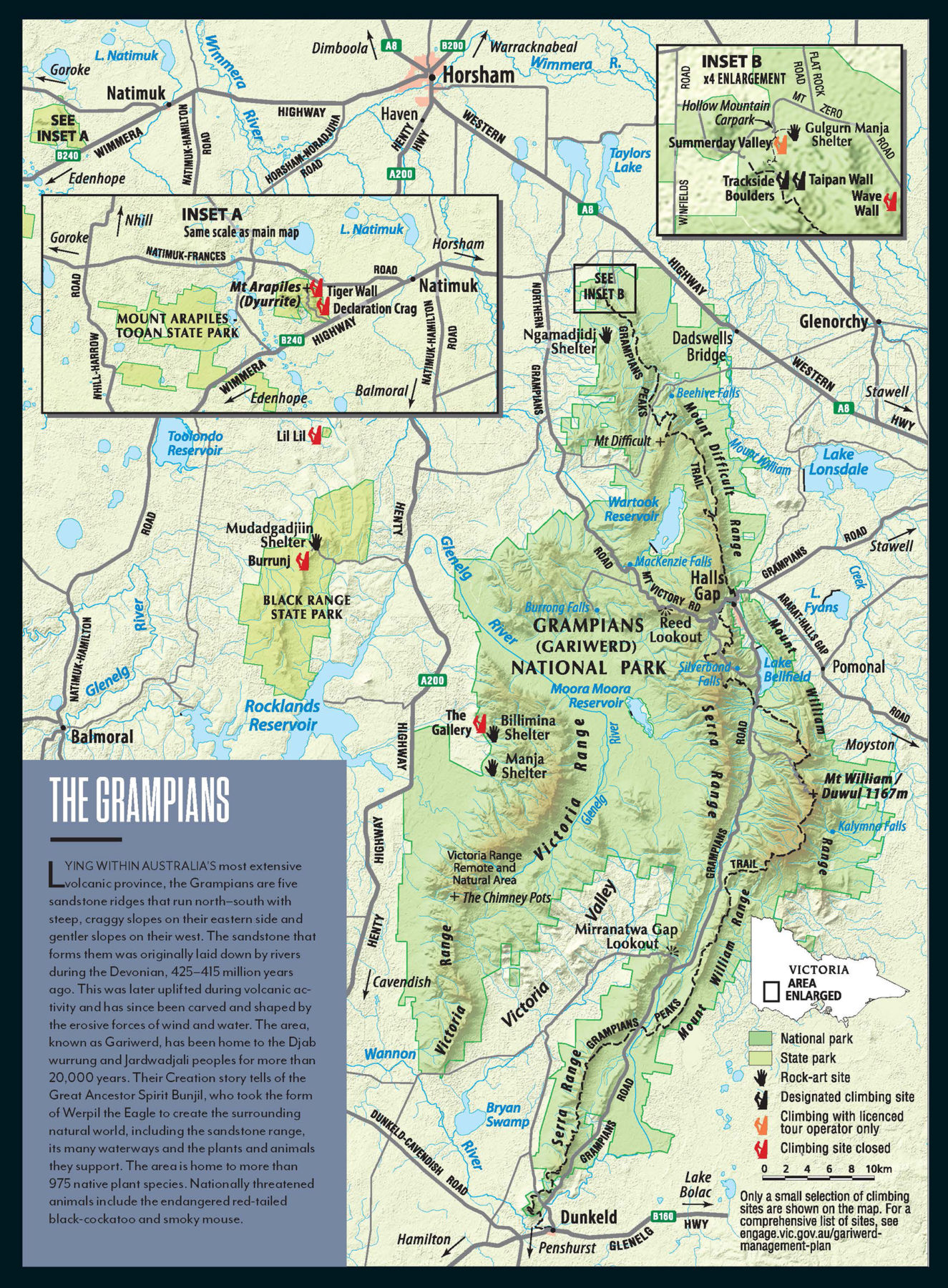

At Hollow Mountain car park my climbing partner and I gaze in awe at towering, cornflake-orange escarpments. We walk the track towards them, then at the cliff-line take a faint path through the scrub, guided by a 2015 edition of Neil Monteith’s book Grampians Climbing. An hour later, I lead my first outdoor sport climb, warm sandstone beneath my fingers and joy in my heart. It’s 2018 and I’m experiencing one of the world’s best places to climb for the first time. About 500 crags (climbing areas) and 8700 individual routes await, including the legendary Taipan Wall. It’s not long before I’m at Dyurrite (Mt Arapiles), a rock fortress an hour further north and home to thousands of trad (traditional) climbing lines.

My life soon revolves around climbing and I begin editing Argus, the newsletter of the Victorian Climbing Club (VCC). In early 2019, I’m shocked to find climbing is now banned in a third of Grampians NP. Parks Victoria has declared 55,100ha off-limits and knocked out key crags popular for sport climbing, trad climbing and bouldering. The bans have been made pending cultural and environmental heritage assessments. Many of the areas set aside are on the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Register and include rock-art shelters and quarries from where Aboriginal people took stone to make tools. Parks Victoria says a rise in climber numbers, bolts and chalk use prompted the bans. Many climbers consider their environmental footprint to be low and disagree they could be causing harm. But most don’t realise this conflict has been brewing for decades. Gariwerd, as the area is known to its Traditional Owners (TOs) the Djab wurrung and Jardwadjali peoples, contains almost 90 per cent of Victoria’s known rock art. Thousands of motifs attest to the presence, knowledge and spirit of its first peoples. Much of it is on overhangs favoured by climbers, and some is more than 22,000 years old.

“People have been rockclimbing in Gariwerd for well over a hundred years,” says veteran climber Kevin Lindorff. During the 1970s, he was part of the second wave of climbers to venture there before it became a national park in 1984. They hiked to distant cliffs looking for new routes, and mostly left little trace. Occasionally, when they discovered a line that couldn’t be protected with removable or ‘traditional’ gear, they’d hammer in a piton (metal spike) or drill a bolt. A few climbing community legends cut goat-tracks, established crags and published guidebooks, encouraging hundreds and then thousands to come and play.

Over the years, more lines got bolted. Tracks were formalised. Climbing gyms opened – five in Melbourne alone during 2015–18, another 10 since 2018 – and the niche pastime went mainstream. Climbing entered the Olympics. Free Solo, a documentary profiling climber Alex Honnold, won an Oscar and Alex even came to Gariwerd to test himself on its world-class sandstone.

But there was a problem: climbing was to have been prohibited from most of the now-banned areas under the 2003 park management plan, but Parks Victoria never enforced the bans at the time. Conversely it worked with climbing’s de facto peak body, the VCC, and its environmental offshoot CliffCare, to improve access to popular crags – Summer Day Valley in 2000, Taipan Wall in 2008, The Gallery in 2012 – with climbers fundraising and volunteering their labour.

“Parks Victoria is now in an uncomfortable and challenging position as it attempts to enforce 15-year-old management and usage rules after having encouraged climbing for so long,” wrote Lucy Welsh in 2020. Lucy is a heritage registry collections manager at First Peoples – State Relations, a group within the state government that works with TOs on cultural heritage management and protection.

Driven by fear of losing what they loved, some climbers turned on Parks Victoria, convinced its upper echelon had an anti-climber agenda. Errors in Parks Victoria’s publicity, such as exaggerated user numbers and false accusations of bolting in rock-art sites, led a core group of mostly hard-grade sport climbers to believe they were being scapegoated. A new website, savegrampiansclimbing.org, spearheaded by guidebook author and crag developer Neil Monteith, seized on these errors, fuelling the groundswell.

Driven by fear of losing what they loved, some climbers turned on Parks Victoria, convinced it had an anti-climber agenda.

Ignorant of the history, most climbers were unsure what to think, myself included. A belligerent minority dominated social media, likening rock art to children’s drawings and questioning its authenticity. Other climbers claimed the bans were a misunderstanding and argued that if they could just sit down with TOs all would be resolved. Mike Tomkins, founder of the fledgling Australian Climbing Association of Victoria, said he wanted to engage with TOs, then flouted the bans. Tracey Skinner, CliffCare’s access and environment officer, who’d been at the forefront of engagement with Parks Victoria since 2007, resigned over the furore before expressing support for TOs. Meanwhile, TOs remained silent.

In mid-2019 Parks Victoria announced a new park management plan for Gariwerd to be co-authored with the bodies corporate that represent the rights and interests of Gariwerd’s TOs: Barengi Gadjin Land Council (BGLC), Eastern Maar Aboriginal Corporation and Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. The planning process provided mechanisms for addressing climber concerns. Kevin Lindorff, who’d emerged as a respected, level-headed representative, would spend the next 18 months challenging the bans through these channels. He argued they were disproportionate and unfair, and “a more fine-grained, cliff-by-cliff focus” that didn’t prohibit any user group from vast tracts of the park indiscriminately was needed. But as months passed, there was no indication climbers’ suggestions were being incorporated.

Meanwhile, more areas were placed off-limits. Popular beginner area Summer Day Valley was the one crag to be partially reopened, to licensed tour operators only, on the condition they completed a cultural heritage induction. Closures began at Dyurrite, in Mount Arapiles-Tooan State Park, co-managed by Parks Victoria and BGLC on behalf of its TOs the Wotjobaluk, Jaadwa, Jardwadjali, Wergaia and Jupagulk peoples. Serious climbers, including Kevin, Glenn Tempest and Louise Shepherd, had moved to the nearby town of Natimuk to be closer to Dyurrite, where many made their livings as guides. By now, savegrampiansclimbing.org estimated 38 per cent of routes in Gariwerd and at Dyurrite were closed. On a good day, climbers joked they still had Taipan Wall. Then, in August 2020, that was struck off.

Soon after, indemnified by the VCC, Kevin and Glenn launched legal action against Parks Victoria. The case was later withdrawn but prompted BGLC to issue a position statement, calling the action “counterproductive and a direct challenge to our rights and cultural responsibilities to protect our heritage values”. BGLC supported Parks Victoria’s protection efforts. “In fact,” it said, “we are the drivers for these very actions.” The draft management plan confirmed this, acknowledging that “for more than 22,000 years, Gariwerd was, and remains, the living, hunting, gathering, cultivating, ceremonial, Dreaming Country and territory of Jardwadjali and Djab wurrung language groups and their ancestors”.

The plan prioritised TO aspirations for the park, including strengthening cultural tourism, reintroducing traditional fire management practices, and focusing on Gariwerd as a place of healing. It also flipped the approach to climbing: to be prohibited throughout the park, except in areas deemed open or pending.

Many climbers struggled to understand that TOs had power and agency, when for almost 200 years they’d had none. Within a decade of colonists arriving in 1837, after Major Thomas Mitchell’s 1836 expedition to the area, the Jardwadjali and Djab wurrung peoples lost their land and with it their means of subsistence. By 1845 most were dead from either attacks, introduced diseases, poisoning or starvation. Survivors were later relocated to reserves where the systematic erasure of culture and custom continued.

“Other climbers claimed the bans were a misunderstanding and argues that if they could just sit down with Traditional Owners all would be resolved.

A group of climbers who understood that the bans were part of broader conversation efforts was Gariwerd Wimmera Reconciliation Network (GWRN). Created in response to the “critical need to form positive and enduring relationships with Traditional Owners”, its goal wasn’t to convince TOs that climbing and cultural heritage should coexist, but to provide information about the sport so TOs could make their own decisions.

GWRN recognised TOs’ legal right to decide what’s best for themselves and their communities as a vital part of the reconciliation process. GWRN was invited to participate in the cultural heritage assessments, something the VCC had not managed to achieve.

Gariwerd has always been a place of “immense spirituality” and “gathering”, according to Gunditjmara leader Damein Bell. “It connected Countries,” he told Joe Hinchliffe from The Age after drawings of a bunyip were rediscovered during the making of the Grampians Peaks Trail.

He described the sites as “revelations”. Former Eastern Maar CEO Jamie Lowe recalled seeing the fingerprints of his ancestors as one of “the most cathartic experiences” of his life.

Jamie went on to say the population of his people, the Djab wurrung, dropped as low as 50. “If you take 90 per cent of people out of any society, what goes with them is a whole lot of cultural knowledge and power.” Rediscovering cultural heritage sites helps put pieces of the puzzle together.

As of May 2020, Gariwerd has 474 registered Aboriginal places, with stone artefact scatters accounting for almost half. There are 132 rock-art shelters, most located in the Victoria Range, the same area that contains the best and hardest climbing. More places are being found all the time: 37 were rediscovered during the initial cultural heritage assessments of 125 climbing sites.

Sixteen years ago, the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 was set up to protect Aboriginal cultural heritage in Victoria and to give TOs control over it, recognising them as “primary guardians, keepers and knowledge holders”. Under the Act, both tangible and intangible heritage can be added to the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Register. Tangible heritage includes physical evidence of past occupation, such as rock art, scarred trees and quarries.Intangible heritage includes stories, knowledge and rituals. Despite this, cultural heritage in Gariwerd was poorly protected before the 2019 bans.

There are 132 rock-art shelters, most located in the Victoria Range, the same area that contains the best and hardest climbing.

Lil Lil is a small cliff-line in the Black Range known for its crack climbs, with a rock-art shelter (a cave) in the middle. The area has five registered art sites, faint but visible. Back in 1998, Parks Victoria met with the VCC to point out the art and request the club’s help in asking climbers to keep out of the cave, which had bolted routes close to artwork. Signage was later installed at the start of the walk-in, asking climbers not to bolt. Most did the right thing. But in 2017 a new bolted route was found near an art panel on the main face.

Crag developers have been quick to dismiss bolting and chalk use as reasons for the climbing bans, seeing bolts as barely visible safety infrastructure, and arguing chalk can be brushed off. But documents show the incident of bolting at Lil Lil and another at Burrunj were catalysts for the climbing bans, as was development in the Victoria Range.

Concerns were initially raised by Parks Victoria’s umbrella organisation, the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP), which sought advice from Aboriginal Victoria, now First Peoples – State Relations. In response, Parks Victoria undertook an audit of rock-art shelters in the greater Grampians. Archaeologists employed by Parks Victoria highlighted problems with bolting and chalk use at Lil Lil and The Gallery, classing the use of chalk – magnesium carbonate – within an Aboriginal cultural site as causing “damage comparable to graffiti”. BGLC said in its position statement: “When Traditional Owners see visitors trampling over ceremony sites or artifact scatters, or see climbing bolts drilled into the bones of our Creation Ancestors or around our rock art, it is a cause of enormous distress.”

Bolting has been a contentious issue in the Grampians for more than 20 years. CliffCare’s Tracey Skinner first brought it to the attention of the VCC in 2007, noting the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 could affect climbers’ access to routes in Gariwerd. “Development of new climbing areas without permission, besides being against Park rules, can directly contravene the Act,” she wrote. “Maybe a little extra thought needs to be taken when choices are made. And whether the future consequences [are] worth it.” From 2015 Skinner’s requests became more frequent, culminating in a moratorium on all new route development in Gariwerd in 2018. By then it was too late.

Crag developers knew of the issue. In Grampians Climbing (2015), Neil Monteith called bolting “borderline illegal” and advised developers not to use power tools within “earshot of tourists” or bolt near rock art. However, there had been few repercussions, so perhaps developers saw no reason to stop.

I ask Jason Borg, Parks Victoria’s regional director, western region, why climbing wasn’t banned from culturally sensitive areas earlier. “I think historically it was Parks Victoria trying to do the right thing by everyone, but not getting it right,” he says. “Our relationship to Traditional Owners is stronger now and our understanding of how to protect cultural values is different.”

The legislation is stronger now too. In 2016 members of Gariwerd’s three TO corporations filed for native title over Grampians NP, in response to the state of Victoria wanting to extinguish native title as part of the Grampians Peaks Trail process. The application was withdrawn after it required a single entity to proceed. However, in December 2018 – just 10 weeks before the climbing bans were enacted – the state signed an Indigenous Land Use Agreement with the three corporations, protecting native title from extinguishment. It also committed parties to their responsibilities under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006.

Earlier that same year, the state government passed the Advancing the Treaty Process with Aboriginal Victorians Act (2018), Australia’s first-ever Treaty law. This legalised Aboriginal Victorians’ right to self-determination and signalled the government’s commitment to Treaty.

That same year, the Parks Victoria Act 2018 also saw Parks Victoria come out from under the umbrella of the DELWP. While still reporting to the minister for energy, environment and climate change, Parks Victoria had more direct accountability: it was re-established as an independent statutory authority, with its Board responsible for land managed by Parks Victoria.These changes meant when it came to the protection of cultural values, Parks Victoria “had its hands tied”, as one climber described it to me. After all, it is an organ of government. If policy changes, so too does its mandate.

The Greater Gariwerd Landscape Management Plan, finalised in December, was developed with the intention the park will be jointly managed in the future.

“The important point to come back to is the reset we’ve undertaken at Parks Victoria around seeing Gariwerd as a cultural landscape, first and foremost,” Jason says. “Essentially, we’re trying to future-proof the park so that cultural heritage values and natural values are protected, but still allowing enough opportunity for people to recreate.”

About 100 crags remain open. Bouldering, virtually erased from the draft plan, is permitted in 13 sites, while a section of Taipan will be reopened to climbers, as will several other areas. Summer Day Valley remains open to licensed tour operators only. “The positive changes that have been made have had to be fought for,” Kevin Lindorff says. “Almost all of the very few climbing areas that have been reclassified since the draft plan were subjects of detailed, logically argued Regulation 67 applications to climb. The refusals of these applications triggered a legal challenge, and though [it] was halted, the classifications were subsequently changed.”

TOs’ generosity in reopening areas should be noted. Jason says there is funding for this calendar year to assess priority crags put forward by climbing’s nascent peak body. A free permit for climbing will be introduced to ensure climbers complete a cultural heritage induction, and chalk must match the colour of the rock. Bolting will be permitted in designated climbing areas. Other user groups have also been impacted to a lesser extent: off-track walking is now prohibited in Special Protection Areas, and dispersed camping will be phased out by 2024. I ask Louise Shepherd, one of the first climbers to move to Natimuk in the 1980s, if she thinks Parks Victoria has done enough. She says it “did make an effort” and “we need to move forward”.

At Dyurrite, cultural heritage assessments were due to be completed by June. Louise says the feeling in Natimuk is varied, but overall people are “incredibly respectful” of the request to keep out of closed areas. “I think climbers across the board have an awareness that things are going to change and there are other people for whom Dyurrite is very important.”

The partial reopening of Taipan Wall, facilitated by GWRN, gives Louise hope for Dyurrite. “I think GWRN is doing a fantastic job and I really support them…I think it’s the way forward.”

Gariwerd’s TOs declined to be interviewed for this story, as did Gariwerd Wimmera Reconciliation Network.