In May 1990, when the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) announced plans to replace Caroline Chisholm with the Queen on a new $5 note, the decision stoked growing republican sentiment and unleashed a fiery backlash about the representation of Australian women on banknotes.

Paul Keating called the decision a “national disgrace”. Historian Manning Clark described it as “deplorable” and “retrograde”. The mauve-coloured fiver was the first of a series of new polymer banknotes to be issued between 1992 and 1996 and there were concerns about what it might mean for the designs of the remaining notes, which had yet to be revealed.

The initial series of decimal currency, featuring 11 men and the Queen, was released in 1966, followed by a $5 note in 1967 depicting Caroline Chisholm, a 19th-century humanitarian, and the only Australian woman on the notes. Yet almost three decades later, she was first to go from the new polymer series.

As well as formulating monetary policy and maintaining a strong financial system, the RBA, which was established in 1960, is responsible for issuing currency and that includes producing banknotes. Its decision to replace Chisholm on the $5 note came in the wake of decades of campaigning for women’s equal representation across all aspects of Australian society. That sparked anger and disgust from the Women’s Electoral Lobby (WEL), which called for 50 per cent of the faces on banknotes to be of women. Labor MP for the Queensland seat of Forde Mary Crawford said the decision showed “total disregard for women and women’s place in our society”. Hundreds of schools and citizens petitioned the Parliament, urging the bank to reconsider.

At the time prime minister Keating, opposition leader John Hewson and National Party leader Tim Fischer all publicly agreed. The House of Representatives even adopted a rare bipartisan resolution expressing concern about the bank’s decision to remove Chisholm, and recommended the decision be rescinded, a report in The Sydney Morning Herald on 30 June 1992 recorded.

Opinion writers of the day proposed women more suitable than the Queen, ranging from May Gibbs and Phyllis Cilento to Germaine Greer and Sophie Lee. Subsequently Australia Post weighed in, printing Chisholm’s portrait on a new set of travellers cheques. “Economically and financially, it was a pretty torrid time,” explains Selwyn Cornish, an economic historian at the Australian National University (ANU) and the RBA’s official historian. Selwyn says the introduction of the new banknotes coincided with Australia’s 1991 recession and the collapse of a couple of state banks. He says that ultimately the RBA’s board decides who’s on our banknotes – not the Parliament or the people.

In 1992, the RBA stuck staunchly by its decision to put the Queen on the Australian $5 note instead of Chisholm, citing the established tradition of depicting the monarch on our currency. But it also acknowledged there had been a “mixed reception” to its decision and early in the saga RBA spokesperson Peter McWilliam assured The Canberra Times “a woman will be represented, and possibly more”.

Soon, the bank revealed, a different woman would, in fact, be depicted on every single banknote. It was a decision that three decades later remains world-leading.

As well as carrying an image of the Queen, the polymer notes, which are still in circulation, feature palm-sized portraits of writer Dame Mary Gilmore, businesswoman Mary Reibey, first female member of an Australian parliament Edith Cowan and soprano Dame Nellie Melba. Australia remains the only country with a different woman depicted on every banknote, well ahead of the next best nations Denmark and Sweden.

Given that women feature on only about 15 per cent of banknotes globally, it’s a striking achievement, particularly when compared with USA’s greenbacks, where all the faces are currently men, despite efforts to have African American activist Harriet Tubman put on the $20 bill.

“If you look at the changes in the people who appear on the banknotes…it can tell us quite a bit about our own social history and our thinking as a nation,” Selwyn says. There was a “preponderance of males” on the decimal notes of 1966, he agrees. As women became more prominent in Australia’s parliament, business and academia, that’s been reflected in the portraits on the notes.

Julie McCarron-Benson says the decision to honour women equally on Australia’s currency will be important for coming generations. Julie was the national coordinator of the WEL back in 1992 and among those calling for 50:50 representation.

“If they’ve got women portrayed in positions of esteem and respect, it does have an effect on [both] boys and girls. The boys don’t question that women can do things, and the girls don’t question that they can do them,” Julie says.

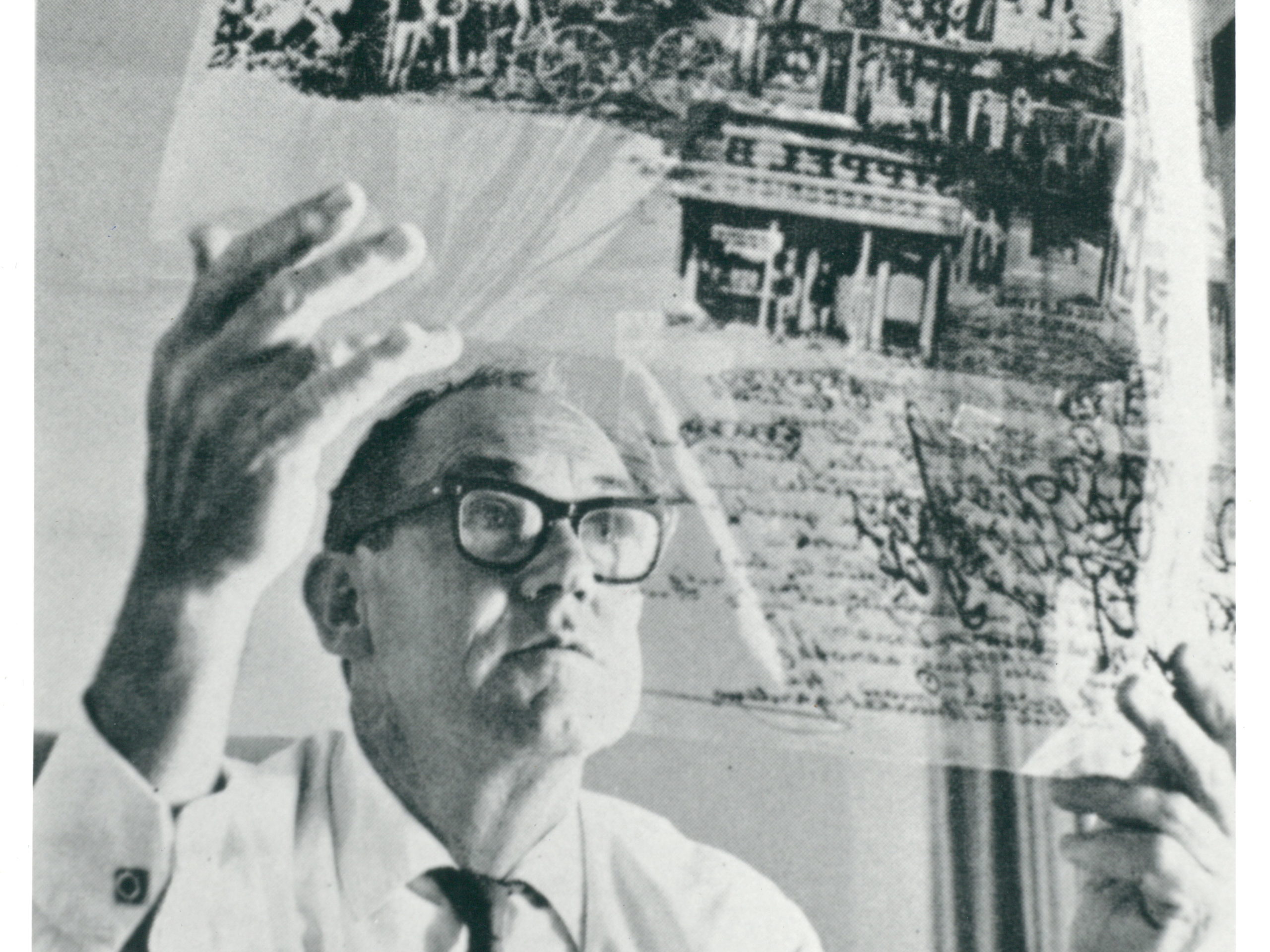

New bank note designs are often contentious, says Mick Vort-Ronald, who has collected and studied Australian banknotes since the 1960s and self-published about 150 books and numerous articles on the subject.

“Every time the government announces they’re going to put someone new on a banknote the media get stuck into it and advise people to write in about who they want,” he says.

Mick suspects that’s why for the latest banknote series – the Next Generation Banknotes progressively released between 2016 and 2020 – the RBA decided to stick with the same historic people, “instead of running the gauntlet of changing the designs”. According to the RBA, designers, artists and historians were consulted and it was decided to “retain many of the salient characteristics of the current series, including the people portrayed on the banknotes” to reflect Australia’s cultural identity.

Historian and ANU professor Angela Woollacott was one expert approached to join a new panel to assist with the Next Generation designs back in 2011. She says the bank made it clear from the outset that the main elements of the notes – the people, their face values and even the overall colour palette – weren’t up for discussion.

Yet this didn’t stop her and others on the advisory panel from agitating for the removal of the monarch. “Several of us at the beginning tried hard to convince them that it was time to switch from the Queen,” she reveals.

The panel’s role was constrained to advising on how historic people should be represented, as well as the aspects of their careers and historic significance that should be highlighted. For example, Angela and others on the panel wanted to ensure that the new $50 note emphasised Edith Cowan’s role as the first woman elected to any Australian parliament. As such, the new design includes microtext from her maiden speech to the Western Australian parliament, as well as text from the private bill Cowan introduced that became the Women’s Legal Status Act 1923.

Few people would know also that the abstract white diagram on the note is “actually the floor plan of the lower house of the Western Australian parliament at the time she [Cowan] was in it”, Angela says.

Australia didn’t have a national currency before Federation. But women were often depicted on the banknotes issued by private and state banks before 1901, Mick says. However, these weren’t real women, but rather allegorical figures who were portrayed by stock images used by banknote printing companies at the time. These fictional females wore laurel crowns and classical robes, and were occasionally depicted carrying a sheaf of wheat or scroll of paper or holding a lamb.

Since Federation, Australia’s banknote designs have changed several times. The first set to feature significant historic, mainly colonial, figures, such as Matthew Flinders and Arthur Phillip, was issued in 1954. Banknote design changes in Australia have been prompted by events such as the succession of a new king or queen, in 1966 by the switch to decimal currency, and later by the development of new banknote security technology.

A woman on every bank note

Image credits: Contemporary banknotes: shutterstock, Dame Mary Gilmore: courtesy Daphne Mayo Collection/University of Queensland, Edith Cowan: courtesy State Library Of Western Australia, Dame Nellie Melba: courtesy John Oxley Library/State Library of Queensland.

DAME NELLIE MELBA

World-renowned soprano Dame Nellie Melba, who’s on our $100 bill, was also the first Australian to grace the cover of Time magazine, in 1927.

EDITH COWAN

The first woman in an Australian parliament, Edith Cowan, appears on the $50 note, wearing the gumnut brooch she had made to symbolise entry into Parliament for women as a “tough nut to crack”.

MARY REIBEY

The $20 note celebrates Mary Reibey, who arrived as a convict charged with horse stealing but became a highly respected businesswoman running successful shipping and trading operations.

DAME MARY GILMORE

The hut depicted on the $10 note, which carries a portrait of poet Dame Mary Gilmore references the life in the Australian bushland that she described in her poetry.

QUEEN ELIZABETH II

The image of 19th-century Australian humanitarian Caroline Chisholm graced the original $5 banknote, but was replaced by that of the Queen on the new polymer version in 1992.

Who will replace the Queen?

While the RBA dodged a public conversation with the Next Generation Banknotes, Australia’s $5 note will face unavoidable design changes now that the Prince of Wales has ascended the throne. It’s a change that would tip the gender ratio back towards men and has sparked a new public discussion about who should be on the note.

The question has arisen as to whether the RBA will stick with the tradition of putting the reigning monarch on the lowest denomination banknote. “That will be a fascinating moment for banknote design,” Angela says.

“I suppose it would be rather controversial if they didn’t put the reigning monarch on them,” Selwyn says. But, he says, this could also open up an opportunity to put eminent Australians on the $5 note instead, like on the other notes. “Whichever way they go, they’re going to be criticised, no doubt,” he says.