Being at the heart of some of the world’s most fertile grain-growing land, Victoria’s Wimmera is a prosperous place. In 2022 plentiful rainfall and soaring commodity prices brought local farming families a particularly generous bounty – a once-in-a-generation boom. But even as this story of plenty plays out, there’s another of decline unfolding behind the scenes. Demographic changes mean many small towns that once dotted the Wimmera are fading. Some, such as tiny Antwerp, Kiata and Gymbowen, are close to disappearing. Others, including Nhill, Warracknabeal and Minyip, have suffered large population declines since their 1950s and ’60s heydays.

To capture the Wimmera’s declining towns and the people who live in and around them before it’s too late, I recently worked with a team of documentary photographers to produce The Wimmera: A Journey Through Western Victoria. We found the people and places that feature in the book by following a 1950s railway map, created when Victoria’s railway network was at its peak. This allowed us to infiltrate places throughout the Wimmera. Each chapter follows a different line, some of which are still used today, while many have been closed for decades.

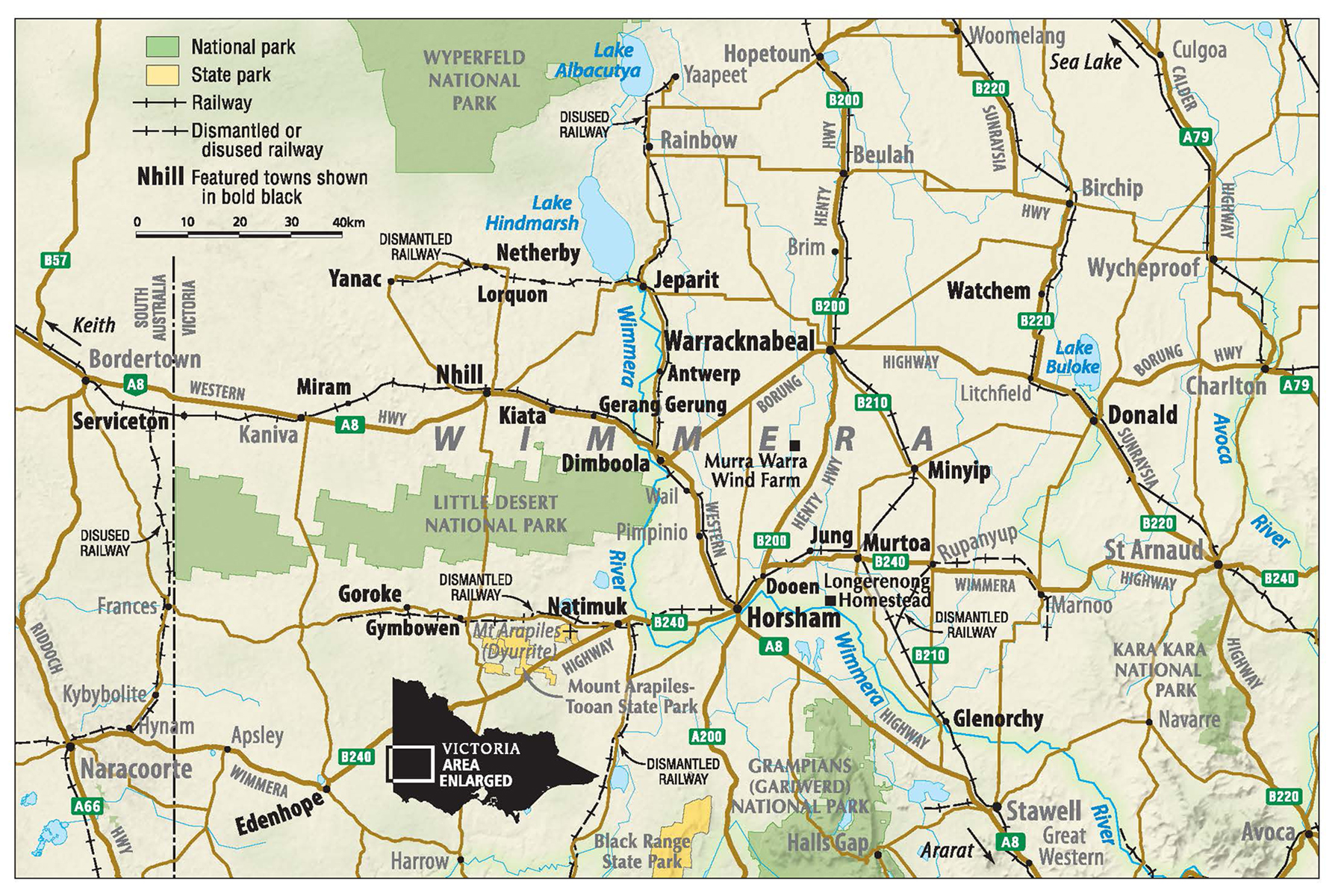

The region extends from the towns of Donald and Watchem in the east all the way to the South Australian border in the west. It neighbours the drier and harsher Mallee region in the north. And in the south it abuts the lush plains of the Western District, home to Victoria’s long-established and wealthy landowners of the state’s original squattocracy. For the book, we set borders loosely rather than use those of formal organisations such as the Bureau of Meteorology. If people told us they considered themselves to be in the Wimmera, that was good enough.

The negative changes in the region have come about for a range of reasons. The lure of city life is a major one. For many years, people have been moving from the smaller towns to Horsham, which has become the Wimmera’s capital, boasting a population of more than 20,000. Others have moved further afield, to the closest capital cities, Adelaide and Melbourne.

But ever-improving farming technology has probably had the most impact on the Wimmera’s demographics. Giant tractors and harvesters have enabled farms to grow larger while needing ever-diminishing amounts of human labour. Where once there was a family eking out a living on each 130ha block, most farming businesses in the region now control thousands of hectares and turn over millions of dollars.

We began our journey by following a section of the railway line that still carries passengers and freight between Melbourne and Adelaide, joining the line at Glenorchy. This tiny town sits next to the Wimmera River, known as Barringgi Gadyin in the language of the Wotjobaluk – the region’s Traditional Owners.

The river flows through the region and has sustained the local First Nations people for tens of thousands of years. Glenorchy has been all but abandoned, and its population figures are illustrative of the broader Wimmera story. Glenorchy’s population peaked at 428 in 1911, but by the 2016 census it was 125.

Following the line towards Adelaide, we visited Murtoa, home of the Stick Shed. This extraordinary structure was built as an emergency grain store during World War II, when there was a grain glut. It now attracts scores of tourists who marvel at its cathedral-like feel.

Next, we called in at Longerenong Homestead, a relic from the days when squatters laid claim to vast swathes of land. Built for Irish pastoralist Sir Samuel Wilson in the mid-19th century, the homestead was once among the grandest residences in rural Victoria. There was little demand for Gothic-inspired homesteads after WWII, so the building was used for a time as a hay shed. It’s now being restored to its former glory.

Further west, we stopped at the tiny outpost of Jung, where much of the movie The Dressmaker, starring British actress Kate Winslet, was filmed, then took in the Friday night meat-tray raffle at the Dooen pub, and passed through the bustle of Horsham. Then it was north to the enormous Murra Warra Wind Farm. So flat are the Wimmera plains, the giant turbines, which will eventually power half a million homes, can be seen from many kilometres away.

Not far past the wind farm, we reached Dimboola, a town infamously depicted in the 1979 movie of the same name. The pub that features in the film, and its trademark watchtower, burnt down a decade ago. However, the town – situated on a beautiful stretch of the Wimmera River and not far from the Little Desert National Park – is rediscovering its verve.

The arrival of treechangers, including Chan and Jamie Uoy, who have opened The Dimboola Imaginarium in an old bank building, has encouraged the community to unleash its creativity. In April, the town held the first Wimmera Steampunk Festival in the main street, with thousands attending.

We continued west from Dimboola and stopped briefly at Kiata, a hamlet where a hall, a few houses and a shuttered pub are all that remain of a town that once boasted a host of services and sporting clubs. For a number of years, Kiata shared a football and netball club with the nearby settlement of Gerang Gerung.

The club was known as Gerang-Kiata and its catchy name helped it amass a cult following among fans of bush footy.

Next stop on our journey was Nhill, where grand buildings lining the main street tell of a place that once bustled. The town’s current population of 1700 is about 500 less than when it was at its peak. Recently, however, the town has benefited greatly from the successful integration of more than 200 Karen refugees who previously lived along the Thailand–Myanmar border.

Not far from Nhill, the railway line led us to a place called Miram. Here we found a classic example of the many tiny settlements built to service farming families on small holdings during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Miram had a population of 216 in 1911. When we visited in early 2021, you could have counted the number of residents on one hand. The old store, run by the Wheaton family for the best part of a century, was then still standing. By the time our book was published in August that year, it was gone.

One of our favourite destinations in the Wimmera was Serviceton, where an extraordinary railway station stands idle next to some disused grain silos and a few tired-looking homes. The station has a grandeur that stems from being a border post between Victoria and SA at a time when Australia’s states functioned as separate countries. Trains heading west from Melbourne and east from Adelaide terminated there. The station housed customs offices where duty was charged for transporting goods from one jurisdiction to another and cells built in the basement housed prisoners being moved between the colonies.

Serviceton’s decline began with Federation in 1901. No longer was there a need for staff such as customs officers. The station’s 1986 closure was due to the shrinking population and diminished role of trains as a mode for moving people and freight between Melbourne and Adelaide. These days, a friendly and knowledgeable bloke named Les Millikin tends to the station and regales tourists with stories of the glory days.

Elsewhere in the Wimmera we visited Minyip, another location used for a movie. Parts of the 2020 thriller The Dry were filmed here. The pub that featured in the film continues to stand proudly in the main street, but is closed to the public. Further east, we called in at Donald, where we met Robin Letts, who, at the age of 91, still edits the local newspaper, The Buloke Times.

The irony of the Wimmera today is that the region remains as prosperous as ever, but the movement of people towards the bright lights of the cities continues unabated. A number of railway lines we followed saw their last train decades ago.

The line that once ran from Horsham to Natimuk, Gymbowen and Goroke (home of acclaimed novelist Gerald Murnane) was closed in the 1980s and the rails and sleepers were soon removed. But the grain silos built here and in each settlement along the line continue as rusting reminders of the era when everything was moved by rail. The line that ran west from Jeparit has a similar history. Retrace the route today and you’ll come to the outposts of Lorquon, Netherby and Yanac.

Each of them was once a bustling little community, but the drift of people to the cities has turned them into near-ghost towns.

The Wimmera: A Journey Through Western Victoria is available from Ten Bag Press.