The Aquarius Festival 50 years on

Nimbin wasn’t always Australia’s counterculture capital. The small dairy farming town in northern New South Wales was on its knees 50 years ago. Isolation from transport routes and tourists and a downturn in the dairy industry led to an exodus of young people. Shops and farms were abandoned and the village was in decline. But it all changed in May 1973; Nimbin burst into the national consciousness as the fledgling alternative lifestyle movement arrived for the Aquarius Festival – and never left.

In the USA there’d been the Summer of Love in 1967 and Woodstock in 1969. Europe and Berkeley College in the USA had seen the student protests of 1968. In Australia Gough Whitlam won the 1972 federal election, abolished conscription and made university education free. Rebellion was in the air and a new generation grew their hair and rejected their parents’ suburban dreams.

Outdoor music festivals were taking off. In 1970 more than 10,000 people gathered at Ourimbah on the NSW Central Coast. Two years later the legendary Sunbury Rock Festival saw 40,000 party on a farm outside Melbourne, and on the same weekend South Australia hosted the Meadows Technicolour Fair. These proliferating rock festivals each sported a single large stage, structured schedule of US-influenced musicians and a drunken crowd.

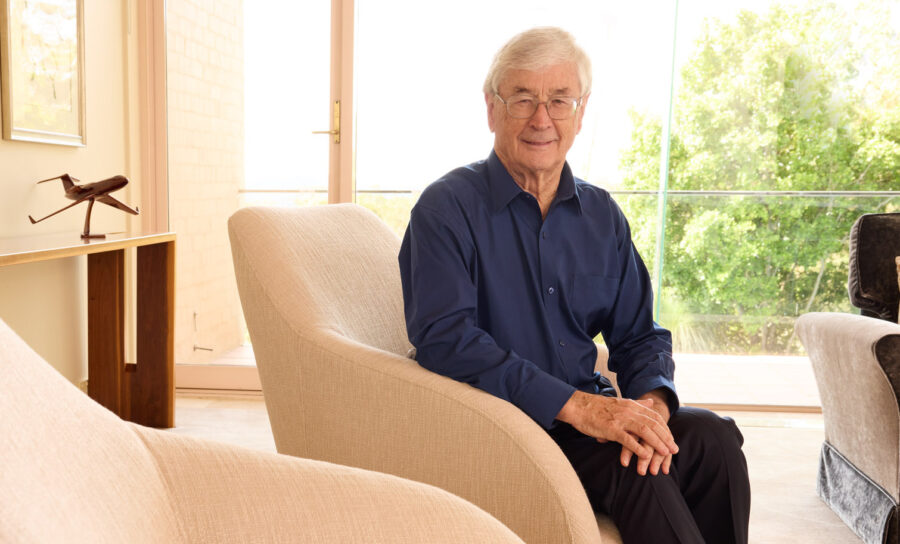

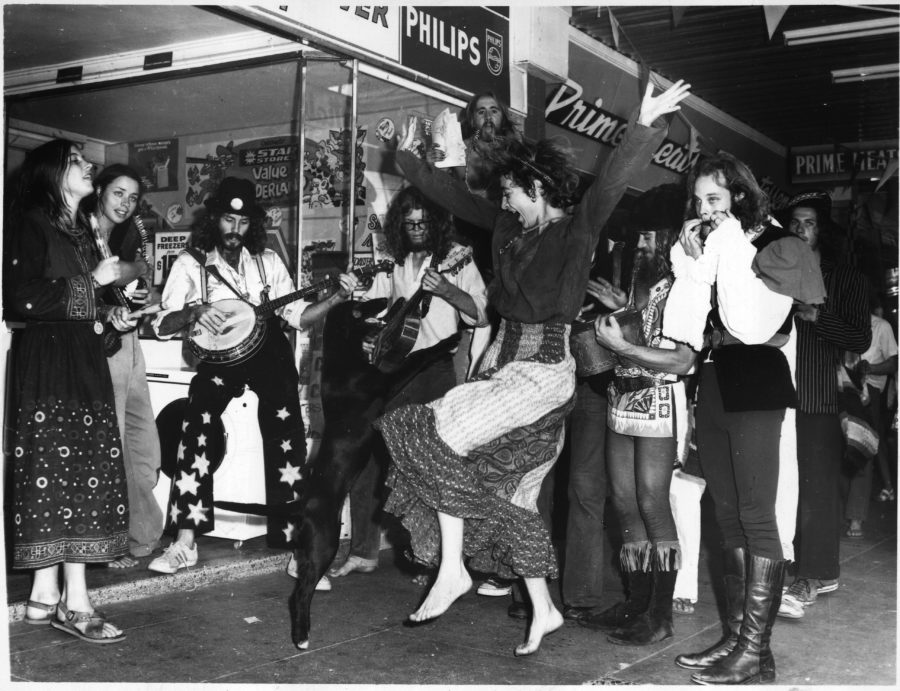

Nimbin’s Aquarius Festival was different. Described by codirector Graeme Dunstan as a “festival without a program”, it was driven by a vision for alternative living, not profit. It was less about bands on stages and ticket sales and more about a celebration of culture, arts and music. Groups gathered organically around scattered campsites or mini-hamlets of teepees, held jam sessions and explored ideas, alternative religions and life philosophies. There were impromtu theatre performances and musical processions, freewheeling acrobatics, sauna sessions and nude yoga classes. “There were people in tree houses [and] elaborate domes…in teepees, almost anything you could imagine – a magical mystery land of all these things,” recalls festival co-director Johnny Allen. Acclaimed poet David Hallett called it “a cross between a boyscout camp and being on LSD”.

The organic spirit, carefree new-age atmosphere and radical intellectual tenor of the event belied the sheer nuts-and-bolts planning and practical effort involved in setting up the festival and the communal settlements that followed. As hundreds of people arrived, deals were made and properties such as the RSL hall and old general store were bought. There were negotiations with locals to use the bakery and the old butter factory. The doctor-less Nimbin hospital was restaffed with festival medics; a food co-op and a printing press for a Nimbin currency were established.

A new Nimbin was born.